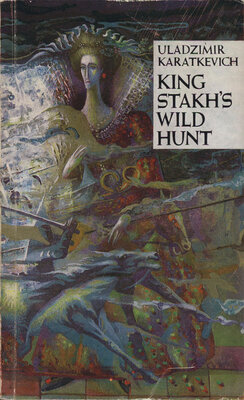

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

Such were the times when I was preparing for an expedition that would take me to the remote provincial District N. I had chosen a bad time for the expedition. It is summer, of course, that is a good time for the ethnographer: it is warm, all around there are attractive landscapes. However, our work gets the best results in the late autumn or in winter. This is the time for games and songs, for gatherings of women spinners with their endless stories, and somewhat later — the peasant weddings. This period is a golden time for us.

But I had managed to leave only at the beginning of August, not the time for story-telling. One could hear then only the drawn-out songs of harvest time resounding through the fields. All August I travelled about, and September, and part of October, and only just managed to catch the dead of autumn —the time when I might find something worthwhile. In the province they were awaiting things that could not be put off.

My catch was nothing to boast of, and therefore I was as angry as the priest who came to a funeral and suddenly saw the corpse risen from the dead. An old long-neglected fit of the blues tormented me, a feeling that in those days stirred in the soul of every Byelorussian: it was

his lack of belief in the value of his cause, his inability to do anything, his deep pain — the main signs of those evil years, signs that arose, according to the words of a Polish poet, as a result of the persisting fear that someone in a blue uniform would come up to you, and smiling sweetly, say: “To the gendarmery, please!”

I had very few ancient legends, although it was for them that I was on the hunt. You probably know that all legends can be divided into two groups. The first are those that are alive everywhere amidst the greater part of the people. In the Byelorussian folklore they are legends about a queen, about an amber palace, and also a great number of religious legends.

And the second are those which are rooted, as if by chains, in some one locality, district, or even in a village. They are connected with an unusual rock or cliff at the bank of a lake, with the name of a tree or a grove or with a particular cave nearby. It goes without saying that such legends die out more quickly, although they are sometimes more poetic than the wellknown ones, and when published they are very popular.

I don’t know how it is with other ethnographers, but it has always been difficult for me to leave any locality. It would seem to me that during the winter that I had to spend in town, some woman might die there, the woman, you understand, who is the only one who knows that enchanting old tale. And this story will die together with her, and nobody will hear it, and my people and I shall be robbed.

Therefore my anger and my fit of the blues should not surprise anyone.

I was in this mood when one of my friends advised me to go to the District N., which was

even at that lime considered a most out-of-theway place.

Did he have any idea that I would almost lose my mind because of the horrors facing me there, that I would find courage and fortitude in myself, and discover?... However, I shall not forestall events.

My preparations for leaving did not take me long: I packed the necessary things into a medium-sized travelling-bag, hired a carriage, and soon left the “capital city” of a comparatively civilized region to take leave of all civilization as I came to the neighbouring district with its forestry and swamps, a territory which was no smaller than perhaps Luxemburg.

At first, along both sides of the road were the fields, and among them were scattered here and there wild pear trees resembling oaks. We came across villages on our way in which whole colonies of storks lived, but then the fertile soil came to an end and endless forest land appeared. Trees stood like columns, the brushwood along the road deadened the rumbling of the wheels. The forest ravines gave off a smell of mould and decay; sometimes from under the very hoofs of the horses flocks of heath-cocks would rise up into the air (in autumn heathcocks always bunch together in flocks) and here and there from beneath the brushwood and heather brown or black caps of nice thick mushrooms were already peeping out.

Twice we spent the nights in small forest lodges, glad to see their feeble lights in the blind windows. Night-time. A baby is crying, something in the yard seems to be disturbing the horses — a bear is probably passing nearby, and over the tree-tops, over the ocean — like forest a solid rain of stars.

In the lodge it is impossible to breathe, a little girl is rocking the cradle with her foot. Her refrain is as old as the hills:

Don’t come creeping on the bench, Pussy-Cat, I’ll beat your little paws.

Don’t come creeping on the floor, Pussy-Cat.

I’ll beat your little tail!

A-a-a!

Oh, how fearful, how eternal and immeasurable is thy sorrow, my Byelorussia!

Night-time. Stars. Primitive darkness in the forests.

And nevertheless even this was Italy in comparison with what we saw two days later.

The forest was beginning to wither, was less dense than before. And soon an endless plain came into view.

This was not an ordinary plain throughout which our rye rolls on in small rustling waves; it was not even a quagmire... a quagmire is not at all monotonous. You can find there some sad, warped saplings, a little lake may suddenly appear, whereas this was the gloomiest, the most hopeless of our landscapes: the peatbogs. One has to be a misanthropist with the brain of a cave-man to imagine such places. Nevertheless, this was not the product of the imagination, here before our very eyes lay the swamp...

This boundless plain was brownish, hopelessly smooth, boring, gloomy.

At times we met great heaps of stones, at times it was a brown cone. Some godforsaken man was digging peat, nobody knows why,— at times we came across a lonely little hut along the roadway, with its one window, with its chimney sticking out from the stove, with not a tree anywhere around. And the

forest that dragged on beyond the plain seemed even gloomier than it really was. After a short while there began to appear little islands of trees even on this plain, trees overgrown with moss and covered with cobwebs, most of them as warped and ugly as those in the drawings that illustrate a horribly frightening tale.

I was ready to weep out loud, such resentment did I feel.

And as if to spite us, the weather changed for the worse: low dark clouds were creeping on to meet us, and here and there leaden strips of rain came slanting down at us. Not a single crested-lark did we see on the road, and this was a bad sign: it would rain cats and dogs all night through.

I was ready to turn in at the first hut, but none came in sight. Cursing my friend who had sent me here, I told the man to drive faster, and I drew my raincloak closer around me.

But the sky became filled with dark, low rain-clouds; over the plain there descended such a gloomy and cold twilight that it made me shiver. A feeble streak of lightning flashed in the distance.

No sooner did the disturbing thought strike me that at this time of the year it was too late for thunder, than an ocean of cold water came pouring down on me, on the horses and the coachman.

Someone had handed the plain over into the clutches of night and rain.

And the night was as dark as soot, I couldn’t see my fingers even, and only guessed that we were still moving on because of the jolting of the carriage. The coachman, too, could probably see nothing and gave himself up entirely to the instincts of the horses.

Whether they really had the instincts I don’t know: the fact is that our closed carriage was thrown out from a hole onto a kind of hillock and back again into a hole.

Lumps of clay, marsh dirt and paling flew into the carriage, onto my cloak, into my face, but I resigned myself to this and prayed for only one thing: not to fall into the quagmire. I knew that the most forsaken places are met with in these marshes — the carriage, the horses, and the people, all would be swallowed up — and it would never enter anybody’s mind that somebody had ever been there, that only a few minutes ago a human being had screamed there until the thick brown marsh mass had stopped his mouth, that now that being was lying together with the horses buried six metres down below the ground.

Suddenly there was a roar, a dismal howl: a long, drawn-out howl, an inhuman howl... The horses gave a jerk... I was almost thrown out... they ran on, heaven knows where, apparently straight on across the swamp. Then something cracked, and the back wheels of the carriage were drawn down. On feeling water under my feet, I grabbed the coachman by the shoulder and he, with a kind of indifference, uttered:

“It’s all over with us, sir. We shall die here!”

But I did not want to die. I snatched the whip from out of the coachman’s hand and began to strike in the darkness where the horses should have been.

An unearthly howl was heard and the horses neighed madly and pulled, the carriage trembled as if it were trying with all its might to pull itself out of that swamp, then a loud smacking noise from under the wheels, the cart bent, jolted even worse, the mare began to neigh! And

Io! A miracle!.. The cart rolled on, and was soon knocking along on firm ground. Only now did I comprehend that it was none other than I myself who had uttered those heart-rending cries. How ashamed I felt!

I was about to ask the coachman to stop the horses on this relatively firm ground, and spend the night there, when the rain began to quiet down.

At this moment something wet and prickly struck me in the face. “The branch of a fir-tree,” I guessed. “Then we must be in a forest. The horses will stop of their own accord.”

However, time passed, once or twice fir-tree branches hit me in the face again, but the carriage slid on evenly and smoothly: a sign that we were on a forest path.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН