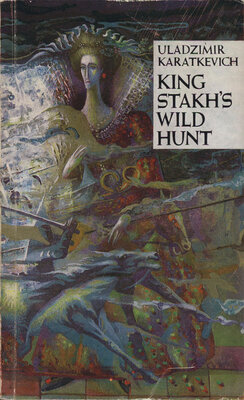

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

as a child does, and sit there. Now for some reason or other it feels good and so quiet here as it has not been for two years, since the time my father died. And it is all the same to me now whether there are lights beyond these windows or not. You know, it is very good when there are people beside you...”

She led me to my room (her room was only two doors away) and when I had already opened the door, she said:

“If old legends and traditions interest you, look for them in the library, in the book-case for manuscripts. A volume of legends about our family must be there. And some other papers as well.”

And she added: “Thank you, Mr. Belaretzky.”

I don’t know why she thanked me, and I confess that I didn’t think about it much when I entered a small room without any door-bolts, and put my candle on the table.

There was a bed there as wide as the Koidan Battlefield. Over the bed was an old canopy. On the floor a threadbare carpet that had been a wonderful piece of work. The bed, evidently, was made up with the help of a special stick (as they used to do 200 years ago), and such a big stick it was. The stick stood near the bed. Besides the bed there were a chest of drawers, a high writing-desk and a table. Nothing else.

I undressed, lay down under a warm blanket, having put out the candle. And immediately beyond the window the black silhouettes of the trees appeared on a blue background, and sounds were heard, sounds evoking dreams.

For some reason or other a feeling of abandonment overcame me to such a degree that I stretched out, drew my hands over my head

and, almost beginning to laugh, so happy did I feel, I fell asleep, as if I had fallen into some kind of a dark abyss over a precipice. It seemed to me I was dreaming that someone was making short and careful steps along the corridor, but I paid no attention to that, and I slept and in my dream I was glad that I was asleep.

This was my first night and the only peaceful one in the house of the Yanowskys at Marsh Firs.

The abandoned park, wild and blackened by age and moisture, was disturbed for many acres around, filled with the noise of an autumn rain.

CHAPTER THE SECOND

The following day was a usual grey day, one of those that often occur in Byelorussia in autumn. In the morning I did not see the mistress of the house. I was told that she slept badly at night and therefore got up late. The housekeeper’s face, when I was having breakfast, was a kind of vinegar-sour face and so sulky and haughty, it was unpleasant to look at her. Therefore I did not stay long at table, took my tattered notebook, five pencils, put on my cloak that had dried overnight, and having asked the way, set off for the nearest “pachynak” — one or two huts in a forest, the beginning of a future village.

I immediately felt better, although nothing in the surroundings made for merriness. Only from here, from this wet footpath, could I take a good look at the castle. At night it had seemed smaller to me, for both of its wings were safely hidden in the thicket of the park and the entire ground floor was completely overgrown with

lilac that had grown wild. And beneath the lilac grew yellow dahlias, pulpy burdock, deadnettle and other rubbish. Here and there as in all very damp places, greater celandine stuck out its web-footed stalks, sweetbriar and solanum grew wild. And on the damp earth amidst the various herbs lay branches white with mould, broken off, apparently by the wind.

Traces of the work of human hands were seen only in front of the entrance where late dark purple asters shone in a large flower bed.

And the house looked so gloomy and cold that it wrung my heart. It was a two-storeyed building with an enormous belvedere, and along the sides were turrets, though not very large ones. Striking was the lack of architecture characteristic of the magnificent buildings of those days when our ancestors ceased building castles, but nevertheless demanded that their architects should erect mansions resembling this moss-overgrown old lair.

I decided to go to the farmstead only after I had examined everything here, and I continued along the lane. The devil alone knows what kind of a fool had thought of planting fir trees in such a gloomy place, but it had been done, and the park which must have been hundreds of years old was only a little pleasanter than Dante’s famous forest. The firs were so thick that two persons together could not have encircled them with their arms, and they approached the very walls of the castle, their branches looking into the windows, their blue-green tops rising above the roof. Their trunks were covered by a grey border of moss and lichen, the lower branches hung down to the earth like tents, and the alleyway reminded one of a narrow path between hills. It was only near the very house

that here and there could be seen gigantic, gloomy almost bare linden trees, dark from the rain, and one thick-set oak, evidently well looked-after, for its top was several metres higher than those of the tallest firs.

My feet stepped noiselessly along the coniferous path. Smoke came from the left and I went in the direction of the smell. Soon the trees were not . so dense and an overgrown wing with boarded-up windows came into view.

. “About half a verst from the castle,” I thought. “If, let’s say, someone took it into his head to kill the owners — nobody would hear anything, even if a gun were fired.”

At the very windows a small cast-iron pot stood on two bricks, and an old hunchbacked woman was stirring something in it with a spoon. The stoves in the wind probably smoked and therefore the food was prepared in the open air until the late autumn.

And again the green but dismal alleyway of trees. I walked until I came to the place where we had entered the park the night before. The marks that our carriage had made were still visible, and the forged-iron fence, a surprisingly fine piece of work, had fallen down long ago, and broken into pieces it lay there thrown aside. Birch trees had grown through its curves. And behind the fence, (here the alleyway turned to the left and dragged on leading to nobody knew where), lay a brown endless plain with twisted trees here and there, enormous stone boulders, and the green windows of the quagmire, (into one of which we had, evidently, almost fallen yesterday), and I grew cold with terror.

A lonely crow was circling above this distressing place.

When I returned home from the farmstead towards evening, I was so exhausted I could hardly pull myself together. I began to think that this would last forever: these brown plains, the quagmire, the people more dead than alive from feverish mania, the park, dying of old age — all this hopeless land was nevertheless my own, my native land, covered in the day by clouds, and in the night by a wild moonlight, or else by an endless rain pouring down over it.

Nadzeya Yanowskaya awaited me in the same room and again that strange expression on her distorted face, that same indifference to her clothes. There were some changes only on the table where a late dinner was served.

The dinner was a most modest one and did not cost the mistress a kopeck, for all this food was prepared from local products. In the middle of the table there stood a bottle of wine and it, too, was apparently from their own cellars. And the rest was a firework of flowers and forms. In the middle stood a flower vase and, in it, two small yellow maple branches, and beside it, though probably from another set, a large silver soup-bowl, a silver salt-cellar, plates, several dishes. However, it was not the lay-out of the table that surprised me or even that the dishes were all from different sets, darkened with age, and here and there, somewhat damaged. What surprised me was the fact that they were of ancient local workmanship.

You no doubt know that two or three centuries ago, the silver and gold dishes in Byelorussia were mainly of German make and were imported from Prussia. These articles, richly decorated with “twists and turns”, with figures of holy men and angels, were so sugary sweet that

it was nauseating, but nothing could be done about it, it was the fashion.

But this was our own: the clumsy stocky little figures on the vase, a characteristic ornament. And the women depicted on the salt-cellar had even the somewhat wide face of the local women.

And also, there stood two wine glasses of iridescent ancient glass which today cannot be bought even for gold (the edge of one wineglass, the one standing at my hostess’s place, was somewhat chipped).

The last and the only sun-ray that day shone in through the window, lighting up in it dozens of varicoloured little lights.

The mistress had probably noticed my look and said:

“This is the last of three sets which were left by our forefather, Roman Zhys-Yanowsky. But there is a stupid tradition that it had probably been presented to him by — King Stakh.”

Today she was somehow livelier, did not even seem to be so bad-looking, she evidently liked her new role.

We drank wine and finished eating, talking almost all the time. It was a red wine, red as pomegranate, and very good. I became quite cheerful, made the mistress laugh, and on her cheeks there appeared two pink spots, not very healthy ones.

“But why did you add to the name of your ancestor this nickname ‘Zhys’?”

“It’s an old story,” she answered, becoming gloomy again. “It seems it happened during. a hunt. An aurochs charged the somewhat deaf king behind his back and the only one who saw it was Roman. He shouted: ‘Zhys’! This in our local dialect means ‘Beware’. And the King

turned about, but running aside, fell. Then Roman at the risk of killing the King, shot, the bullet struck the aurochs in the eye, and the aurochs fell down almost beside the King. After that a harquebus was added to our coat-ofarms and the nickname ‘Zhys’ to our surname.”

“Such incidents could have occurred in those days,” I confirmed. “Forgive me, but I know nothing that concerns heraldry. The Yanowskys, it seems to me, go back to the 12th century?”

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН