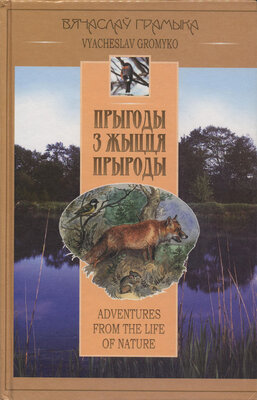

Прыгоды з жыцця прыроды

Adventures from the life of nature

Вячаслаў Грамыка

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 263с.

Мінск 2003

Having hidden itself in the thickest bushes, it could, at last, take breath a bit. The body was trembling incessantly and though it understood well that the danger was already gone, nevertheless, it could not calm down. Having mastered the pain, which was reminding of itself with every careless movement, the hare tried to reach wounds to lick them in one way or another.

In several days he became stronger, began to move more actively finding some bitter grass. But the hare nibbled it as its natural instinct prompted since they were medicinal.

Soon the hare was able to run swiftly, it ran much about the forest, but the lesson it had been taught was not in vain — now it was much more attentive and cautions.

In some time the hare began to call on the clearing, too. It was longing to be there, at least to see its friends. Taught by bitter experience, it did not run off from the thicket surrounding the clearing so as to find in it a reliable shelter at the necessary moment.

His friends have completely changed, they were almost mature hares. The hare felt immediately that it was hardly recognized there and they scrutinized it with even greater surprise than it scrutinized them. At that time their surprise was mixed with derisive gaiety: they were jumping around and some even tried to touch its head with their paws. Nevertheless, it was accepted into the former company, now it could play and feed again and it was much better than to be lonely: melancholy passed away and time ran faster.

Everything around had changed so much compared with those first spring days that now it was even difficult to remember how, being a leveret, it was running on the ground damp after the high water. All forest vegetation had grown to such an extent as if a continuous carpet covered everything in the forest; ground, bushes and trees. The same was happening on the clearings as well as on the river banks. The majority of the wild life had grown-up offspring, young field and forest birds rose on their wings and parents taught them to live independently with inspiration.

Summer was in its second half. From morning till night the sun keep on scorching mercilessly, the grass began to fade and turn yellow a bit, it had lost its former sappiness and acquired a bitter smack. Even leaves had become strangely faded. The food lacked moisture and now and again, the hare was longing to go to the river where the watering place was.

Several times it came down to the deep forest valley where the bank of a small forest river was more sloping and it was possible to approach the water, but every time something prevented it from doing so. Jut at that time the village shepherds brought cows to the pond and the hares, having failed to approach the

water in time, had to come back. When it attempted to approach the river, all of a sudden, it saw a huge wolf on the bank, which scared it to such an extent that despite the thirst, the hare was not daring to leave the thicket for several days.

But it was very thirsty and headed to the river again, this time having chosen the coppice covered with pussy-willow bushes as its place of passage. There was no one on the river. It touched water with its lips and started drinking greedily. Well, soon it seemed to be enough. The hare raised its head, looked around, and only when it made sure that there was no danger, shook its small muzzle sharply and sniffed loudly.

And then it saw itself in the water. No, the hare didn't take its reflection for some of its fellows or, vice versa, its enemy, as it happened sometimes with cats or other domestic animals. But what he saw surprised it. Instead of two ears, as all hares had, there were three ones reflected in the water.

At first the hare did not believe itself, it looked closely, laid its ears on the head, then tried to raise one, the left one — it rose: an ear like an ear, narrow, long, just as every hare might have. Then it tried to raise its right ear, but instead of one two ears rose. The hare was at a loss. It again put the right ear to its neck and tried to raise it. The result was the same. Though ears were narrower, but as long as before.

It could not understand that it was the owl, who had split its right ear apart. Gradually it healed up, but naturally, it failed to grow together since the halves were constantly moving. So, the hare had become three-eared. And suddenly the cry was heard.

“Look, hare! Look! H-a-a-a-re!!!” and then it was raining down:

“Hare! Hare!”

“Lopsided!!!”

“Young hare!”

“Lop-eared!!!”

They were barefooted village kiddies who were going to bathe in the river and took the hare aback. It jumped to one side, to another and rushed along the river following its nose and the kids were shouting in surprise:

“It is three-eared! Hare-The-Torn-Ear...”

This news has been spread around the neighborhood very quickly: a hare with three ears lived in the forest at Slovichy. Kiddies were telling about the show they had seen so excitedly that it turned out that the hare had not three ears, but even four. Just as quickly as among people, the news about the three-eared hare has been spread among the wild life. And it flew though the forest even earlier, from the very moment when having healed itself, the hare visited its acquaintances on the clearing.

Meanwhile, the summer was coming to its end. More and more often the sky was overcast with thick grey clouds, which poured down tedious rains. Leaves on some trees turned yellow and on others — pink and even bright red. They no longer held to branches and were carried away by the wind. Rustling leaves frightened the hare. Now it was difficult to determine the sounds of danger.

The number of birds has decreased noticeably. Most of them, especially the small ones, have disappeared somehow at once, but big ones — storks, geese, cranes — flew off slowly, their long, stretched wedge-like flocks extended one by one, making for distant warm countries. They emitted some pain and sorrow, and they flew unwillingly, driven away by the colds.

It was getting colder day by day, the air became damp, watery. Then winds were added to colds. Rains began to pelt down.

Greyish-red hair no longer warmed The Torn Ear. The situation with forage was getting worse. Forest grasses have faded and dried, remaining leaves have fallen off, but they were bitter and tasteless.

The hare had to change places of feeding. At first, The Torn Ear started calling on the young aspen grove, where the still green grass “sprinkled” out on mowed-down clearings. For day's rest it retreated deeper into the forest and most often hid in brown grass or in a dense coniferous wood, among wind-fallen trees.

More and more often The Torn Ear began to abandon continuous thickets and call on fields: far off from the forest there stretched a wide green field with dense shots of winter

wheat. It was a real salvation for the hare. Before daybreak, The Torn Ear made for the place of its regular supper.

Days went by. Soon the first frosts began to touch wet soil and by the morning both shriveled grass and winter crops were covered with a white film of hoarfrost. Winds became stronger. The sun rarely peeped out from behind the lowering clouds. Nature was waiting for the winter to come.

The Torn Ear was no longer concerned about that, since white fur warmed it properly. The hare has considerably gained strength, its long legs were carrying it easily and swiftly. But how many unknown things awaited it ahead, how many incomprehensible and hard surprises was the destiny preparing for the white hare?

It was the white fur, which let him down. Though it saved the hare from cold very well, it betrayed it against the background of the autumn colors.

The fox was in wait of the white hare at some distance from the river when it was coming down to the water. The predator had learnt the route of its passages and lay in hiding near the path concealing itself behind a small curly fir tree. The fox had rolled up into a ball, pressed the tail to the stomach. Only its sharp black ears seemed not to relax for a moment and tensely “observed” the audible space, faultlessly prompting what was going on around.

The beast of prey did not wait until the hare approached. It was enough for it to feel the hare's whereabouts in proper time and then it, without difficulty, could chase the hare since the white color of its fell would be an excellent orientation for the fox.

Who knows what the result of the chase would be, but for a chance. Running away, The Torn Ear came across the familiar herd of animals.

The dogs noticed the hare and rushed after it. But almost at the same time they saw the fox, which, carried away by the pursuit of the hare, also darted out on the meadow. The dogs at once let the hare alone and strove after the red haired beast.

However, the fox, without any difficulties, confused the mongrels and they were tricked! But nevertheless, they had

saved the hare. If not from death, then at least delivered it from a long chase and forced shelters.

Now The Torn Ear no longer disdained caution. Having understood the treacherous role of its white fell, it tried not to catch an evil eye, stayed for a long time in the most inaccessible and, what was more important, impenetrable thicket in the bushes of jumper and in the brushwood of young fir and pine trees.

It had been hiding itself in this way for whole days, like long ago, at the very beginning of its life, feeling its helplessness. And only when pitch-dark darkness of the night cloaked the cooling forest in thick wreaths, it cautiously crawled out of the thicket and would make for the nearest field.

As before, The Torn Ear avoided open places and concealed itself from an evil eye — now it would live in a dense fir grove, then it would get into the dense wind-fallen trees or lie on its day's rest in a thick dry grass. As of late, it chose a cozy place under the top of a fir-tree overturned by wind.

Cold winds began to blow stronger from the North. Shallow pools and small lakes were covered with ice at once. Only the swift forest river would not give in to frost. At first ice formed along the banks, where it was most thick and strong. And the farther it was from the bank, the more transparent and thinner its crust became and turned into the thinnest fragile edge, from which crystal pieces were torn off by the swift flow. Blocks of icy armor were widening day by day, expanded from the banks, seeing to embrace the water stream completely so as to freeze the turbulent river over.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН