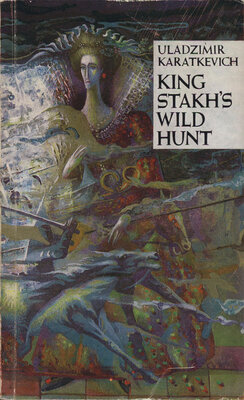

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

These lamentations for a living person were distasteful to me and made me wince.

“You see, you’ve learned something,” Rygor said gloomily.

When we left, the old woman’s wailing quieted down.

“Well then,” Rygor said, “all right, let’s look for them together. 1 want to see this suprising marvel. I’ll try to find out something among the common people, while you’ll look among papers and ask the gentry. And maybe we’ll learn something...”

His eyes suddenly became bitter, the corners of his eyebrows meeting at the bridge of his nose.

“Girls were invented by the devil. All of them should be strangled to death, and the boys fighting among themselves for the few remaining ones, will kill themselves out. But nothing can be done...” Unexpectedly he ended up with: “Take me, for instance. Although my forest freedom is dear to me, still I sometimes think about Zosya, who also lives here. Maybe I’ll live alone all my life in the forest. That’s why I believed you, because I sometimes begin to go mad for those devilish female eyes...” (I didn’t think so at all, but didn’t consider it necessary to convince this bear that he was wrong.) “But, my friend, remember this well. If you have come to stir me up and then to betray me — there are many who have a grudge against me here — so know this — your stay will not be long on this earth. Rygor is not afraid of anybody. Quite the opposite, everybody is afraid of Rygor. And Rygor has friends. It’s impossible to live here otherwise. And his hand shoots accurately. In a word, you must know this, I’ll kill!”

I looked at him reproachfully, and he, glanc

ing at my eyes, burst out laughing loudly, and his tone, as he ended up, was quite a different one:

“And anyway, I’ve been waiting for you a long time. For some reason or other it seemed to me that you wouldn’t leave things alone, and if you took to clearing them up, you wouldn’t pass me by. So well then, why not help each other?”

We parted at the edge of the forest near the Giant’s Gap, arranging to meet in the future. I went home straight through the park.

When I returned to Marsh Firs, twilight had already descended on the park, the woman and her child were sleeping in one of the rooms on the first floor, but the mistress was not in the house. I waited about an hour, and when it was quite dark, I could not bear it any longer and went out in search of her. I hadn’t walked far along the dark lane when I saw a white figure moving towards me in fright.

“Miss Nadzeya!”

“Oh! Oh, it’s you? Thank God! I was so worried! You came straight here?”

Bashfully she looked down at the ground. When we came up to the castle, I said to her quietly:

“Miss Nadzeya, never leave this house in the evening. Promise me that.”

She promised, but only reluctantly.

CHAPTER THE NINTH

This night gave me a clue to the solution of a question that interested me, a question that turned out to be an entirely uninteresting one, save perhaps only in that I once again became

convinced of the fact that stupid people, otherwise generally kind-hearted souls, can be contemptible.

On hearing steps again in the night, I went out and saw the housekeeper with a candle in her hand. I followed her as she went into the room with the closet, but this time I decided not to retreat. The room was again empty, the closet also, but I tried all the boards of the back wall (the closet stood in a niche), then I tried to raise them and became convinced that they were removable. The old woman was probably deaf, otherwise she would have heard me. With great difficulty I managed to push myself through the cracks I had made, and I saw a vaulted passage that led sharply downstairs. The steps worn by time were slippery and the passage so narrow that my shoulders rubbed against the walls. I went down the steps and saw a small room also vaulted. There were two closets there, and along the walls of the room stood trunks bound with iron. Everything was open and everywhere paper and leaves of parchment were lying thrown about. A table stood in the middle, beside it a stool roughly knocked together, and sitting on it the housekeeper was examinig a sheet quite yellowed with time. The greedy expression on her face was shocking.

When I entered she screamed with fright, made an attempt to hide the sheet. I managed to grab her hand.

“Miss housekeeper, give that to me. And be kind enough to tell me why you come here every night to this secret archive, what you are doing here, why you frighten people with your footsteps.”

“Ugh! My God! How fast you are!” she ex

claimed, collecting herself quickly. “He’s got to know everything...”

And, evidently, because she was on the first floor and did not consider it necessary to stand on ceremony with me, she began to speak with that expressive intonation of the common folk.

“And teal and poppy you don’t want? Just see what he needs! And he has hidden the paper. May your children grab your bread from you in your old age as you have grabbed this paper from me. Perhaps I have more right to be here than you. But he, just look, sits there, asking, asking. Damn him!”

This had become boring, and I said:

“What is it you want? Prison? Why are you here? Or perhaps it’s from here you send signals to the Wild Hunt?”

The housekeeper was offended. Wrinkles gathered on her face.

“Sinful, sir!” she quietly muttered. “I’m an honest woman, I’ve come here to get what’s mine. There it is, in your hand. It belongs to me.”

I looked at the piece of paper. It was an extract from a resolution passed by a smallholder claims committee:

“And although the above-mentioned Zakrevsky declares to this very day that he and not Garaboorda is heir to the Yanowskys, this case which has lasted over a period of 20 years, is now closed, as not having been proven, and Mr. Isidore Zarkevsky is deprived of his rights to aristocratic rank for the lack of proof.”

“So what?” I asked.

“This is what, my dear fellow,” the housekeeper came back bitingly, “I am Zakrevskaya, that’s what. And it was my father who went to court with the great and the powerful. I didn’t know about it, but my thanks to some good

people. They told me what to do. The district judge took ten little red ones, but he gave me good advice. Give me that paper.”

“It won’t help you,” I said. “It isn’t really a document. Here the court refuses your father his request, even his right to the gentry is not established. I know about this examination of the petty gentry very well. If your father had had papers to prove his right for substitution after the Yanowskys — that would be another matter. But he did not hand in any papers — and that means that he did not have them.”

The housekeeper’s face reflected a piteous attempt to understand these complicated things.

Then, not believing me, she asked:

“But perhaps the Yanowskys bribed them? These people who raise trifling objections, just you give them some money! I know. They took the papers away from my father and hid them here.”

“And can you sue them 20 years running?” I asked. “Twenty more years?”

“My dear fellow, by that time I’ll have gone to wash God’s portals for him.”

“Well, so you see. And you have no papers. You have searched everything here, haven’t you?”

“Everything, young man, everything. But it’s a shame to lose what’s mine.”

“But they are all only vague rumours.”

“But the money — those red ones and the blue ones — mine.”

“And it is very bad to rummage nights among papers not belonging to you.”

“My dear fellow, the money is mine,” she drawled dully.

“The court will not grant you it, even if there were any papers to prove it. This entailed estate

has belonged to the Yanowskys over a period of 300 years or even longer.”

‘‘But it’s mine, my dear fellow,” almost in tears, and the greed on her face was loathsome to see. ‘‘I would have stuffed them, the dear ones, here, right here in my stockings. I would have eaten money, slept on money.”

“There aren’t any papers,” losing all patience. “There is a lawful heir.”

And. at this moment something awful occurred. The old woman stretched her neck,— it became a long-long one — and with her face close to mine, hissed:

“So perhaps... perhaps... she will die soon.”

Her face even brightened at this hope.

“She will die, and that’s all. She’s weak, sleeps badly, almost no blood in her veins, coughs. It won’t cost her anything to die. The curse will be fulfilled. Why must Garaboorda get this castle when I could live in it? It won’t make any difference to her, her sufferings will be over — and off with her to the holy spirits. While I here would...”

The expression on my face probably changed, for I was furious. She suddenly pulled her head into her shoulders.

“You crow! Come flying to carrion? But it’s not carrion here, it’s a living person. And such a person who is worth dozens of you, who has a greater right than you to live on this earth, you foolish, empty thing.”

“My dear fellow...” she whined.

“Shut up, you witch! And you wish to send her to her grave? You are all alike here, vipers! You are all ready to murder a person for the sake of money. All of you — spiders. For the sake of those blue little papers. And do you know what life is, that it is so easy for you to

speak of another person’s death? I wouldn’t scatter pearls at your feet, but listen to me, you want her to exchange the sunlight, joy, good people, the long life awaiting her, for the worms in the earth? Is that what you want? So that you can sleep on money? The money that the Wild Hunt is seeking here? Maybe it’s you who lets the Lady-in-Blue in? Why did you open the window in the corridor yesterday?”

“Oh, my God! I didn’t open it! It was so cold then. I was even surprised at its being open.” She was almost wailing.

Her face expressed such fear that I could no longer keep silent. I lost all prudence.

“You want her death! You evil dog, you crow! Get out! She’s a noble lady, your mistress. Perhaps she’ll not drive you out, but I promise you, that if you do not leave this house that your stinking breath has polluted, I’ll have all of you put in prison.”

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН