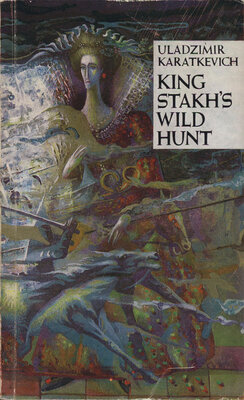

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

We decided not to trouble Berman as yet, so as not to frighten him prematurely.

Then I began to make a detailed study of the letter written by an unknown person to Svetilovich. I used many, many sheets of paper before I managed to restore the text of the letter at least approximately:

“Andrei! I learned that you are interested in the Wild Hunt of King Stakh, and also that Nadzeya Ramanowna is in danger (further

nothing understandable)... my da... (again much missing). Today I spoke with Mr. Belaretzky. He agrees with me and has left for town... “Dryckgants” — chief... When you receive this letter — go immediately to... plain where three pines stand by themselves. Belaretzky and I will wait... ly ma... what’s going on in this world! Come without fail. Burn this letter, because it is very dangerous for me. ...Yo... fr... They are also in mortal danger which only you can ward of... (again much burnt)... me.

Your well-wisher, Likol...”

The devil knows what this is all about! This deciphering gave me almost nothing. Well, once again I became convinced that the crime had been a planned one. And in addition I learned that an unknown “Likol” (what a heathen name!) had cleverly made use of our being on friendly terms, of which only he could have guessed. And nothing, nothing more! Whereas in the meantime an enormous grey stone was laid on the grave of a person who could have been one hundred times more useful for our country than I. And if not today, then tomorrow, such a stone may be weighing down upon me too. And then what will happen to Nadzeya Yanowskaya?

That day brought me yet another bit of news: I received a subpoena. On surprisingly bad grey paper in high-faluting words an invitation to appear at the court in the chief town of the district. It was necessary to leave. We arranged with Rygor about a horse, I told him what I thought about the letter, and he informed me that Garaboorda’s house was being watched, but nothing suspicious had been noticed.

Again my thoughts turned to Berman.

This quiet evening, not at all typical for

autumn, I thought long over what was awaiting me in the district town, and I decided not on any account to remain there for long. I was already about to go to bed and have a good sleep before my trip, when suddenly, on making a turn in the lane, I saw Yanowskaya on a bench covered with moss. A dark greenish light fell on her blue dress, on her hands with fingers interlaced her eyes wandering, an absent-minded look in them, such a look that one sees in a person lost in thought.

The word which I had given myself did not waver, the memory of my dead friend even strengthened this word, and nevertheless for a few minutes I felt a triumphant rapture at the thought that I could have held in my arms this dear slim figure and pressed her to my breast. But bitterly did my heart beat, for I knew that this would never be.

However, I went out to her from behind the trees almost quite calm.

Here she lifted her head, saw me, and how sweetly, how warmly did her radiant eyes begin to shine.

“It’s you, Mr. Belaretzky. Sit down here beside me.”

She was silent for a while, then she said with surprising firmness:

“I’m not asking you why you beat a person so hard. I know that if you did do such a thing, it means it was impossible to have done otherwise. But I am very uneasy about you. You must know: there is no justice here. These pettifoggers, these liars, these — terrible and thoroughly corrupt people can condemn you. And although it isn’t a crime for an aristocrat to beat a policeman, they can exile you from here. All of them together with the criminals form one large union. It will be in vain to beg justice of

them: this noble and unfortunate people will perhaps never see it. But why didn’t you control yourself?”

“I took the part of a woman, Miss Nadzeya. You know, there is such a custom with us.”

And she looked me in the eyes so piercingly that it made me feel cold. How could this child have learned to read hearts, what had given her such strength?

“This woman, believe me, could have endured it. If you are exiled this woman will pay too high a price for the pleasure you received in venting your feelings on some vulgar fool.”

“I’ll return, don’t worry. And Rygor will guard your peace during my absence.”

Without saying a word, she closed her eyes. After a while she said:

“Ah! You haven’t understood anything... As if it is this defence that matters. You should not go to the district town. Stay here for another day or two, and then leave Marsh Firs forever.”

Her hands, their fingers trembling, lay on my sleeve.

“Do you hear, I beg you, beg you very sincerely.”

I was too much taken up with my own thoughts and therefore didn’t quite grasp the meaning of her words, and said:

“At the end of the letter to Svetilovich the signature is ‘Likol’. Is there any such gentleman here in this region whose given name or surname begins like that?”

Her face immediately darkened as the day darkens when the sun disappears.

“No,” she answered, her voice trembling as if offended. “Unless it’s Likolovich... This is the second part of the surname of the Kulshas.”

“Well, it can hardly be that,” I answered indifferently.

And having looked at her attentively, only then did I realize what a brute I was. From under her palms with which she had covered her eyes, I saw a heavy, superhuman lonely tear rolling out and creeping down, a tear that would break down a man in despair, not to speak of a young girl, almost a child.

I am always at a loss and become a cry-baby on seeing women’s or children’s tears, while this tear was such a tear, God forbid anyone should see in his life, the tear in addition of a woman for whose sake I’d willingly be turned into ashes, be smashed into pieces, if that would help to stave off sadness from her.

“Miss Nadzeya, what’s the matter?” I muttered, and involuntarily my lips formed into a smile, the like of which one can see on the face of an idiot attending a funeral.

“Nothing,” she answered almost calmly. “It’s simply that I shall never be... a real person. I am crying for Svetilovich, for you, for myself. It’s not even for him that I am crying, but for his ruined youth,— I understand that well! — for the happiness predestined for us, the sincerity we lack. The best, the most worthy are destroyed. Remember how once you said: ‘We have no princes, no leaders and prophets, and like leaves are we tossed about on this sinful earth.’ We must not hope for anything better, lonely are the heart and the soul, and nobody responds to their call. And life burns out.”

She stood up, with a convulsive movement broke a twig that she was holding in her hands.

“Farewell, my dear Mr. Belaretzky. Perhaps we shall not see each other any more. But to the end of my life I shall be grateful to you... And this is all.”

And here something broke within me. With

out realizing it, I blurted out, repeating Svetilovich’s words:

“Let them kill me — and as a dead man I shall drag myself here!”

She did not answer me, she only touched my hand, silently looked me in the eyes and left.

CHAPTER THE FOURTEENTH

One might suppose that the sun had turned round once (I use the word “suppose” because as a matter of fact the sun had not shown itself from behind the clouds) when I arrived in the district town in the afternoon. It was a small town, flat as a pancake, worse than the most ill-kept of small towns, and it was separated form the Yanowsky region by some 18 versts of stunted forests. My horse tramped along the dirty streets. All around instead of houses were some kind of hen-coops, and the only things that distinguished this small town from a village were the striped sentry-boxes near which stood moustached Cerberuses in patched regimental coats, and also two or three brick shops on a high foundation. Emaciated goats with ironical eyes belonging to poor Jews were looking me over from the decayed, ragged eaves.

In the distance were the moss-covered, tall, mighty walls of an ancient Uniate Church with two lancet towers over a quadrangled dark stone building.

And over all this the same desolation reigned as everywhere: tall birches grew on the roofs.

In the main square dirt lay knee-deep. In front of the grey building of the district court, beside one of the wings, lay about six pigs, trembling with cold and from time to time try

ing unsuccessfully to creep under one another to warm themselves. This was each time followed by offended grunting.

I tied my horse to the horse line and, making my way along squeaking steps, came up into a corridor that smelled of sour paper, dust, ink and mice. A door, covered with worn-out oilcloth, led into the office. The door was almost torn off and was hanging down. I entered and at first saw nothing: such little light came through the small, narrow windows into this room filled with tobacco smoke. A bald-headed, crooked little man, his shirt-tail sticking out at the back of his pants, raised his eyes and winked at me.’I was very much surprised: the upper lid remained motionless, while the lower one covered the entire eyes as in a frog.

I said who I was, gave my name.

“So you have come!” the frog-like man was surprised. “And we...”

“And you thought,” I continued, “I would not appear at the court, would run away. Lead me to your judge.”

The protocol-keeper scrambled out from behind his writing-desk and with stamping feet went in front of me into the midst of this smoky hell.

In the next room behind a large table three men were sitting. They were dressed in frockcoats so bedraggled that it seemed they were made from old fustian. They turned their faces towards me and in their eyes I noticed identical expressions of greediness, insolence and surprise — for I had actually appeared.

These men were the judge, the prosecutor and an advocate, one of those advocates who skin their clients like a plaster and then betray them. A hungry, greedy and corrupt judicial pettifogger with a head resembling a cucumber.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН