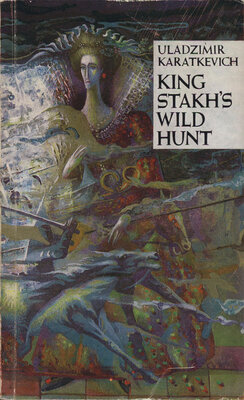

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

Only two persons fit in: Varona and Berman. But then, why had Varona behaved so stupidly towards me? Yes, it was Berman, most likely. He knows history, he could have incited some bandits to commit all those horrors. It’s necessary to find out how Yanowskaya’s death could benefit him.

But who are the Little Man and the Lady-inBlue at Marsh Firs? These questions made my head swim, and all the time one and the same word running in my head.

“Hands... Hands...” Why hands? I am just about to remember... No, it’s again escaped my memory... Well then, I must search for the dryckgants and this entire masquerade. And the quicker the better!

CHAPTER THE FIFTEENTH

That evening Rygor came dirty from head to foot, perspiring and tired out. He sat sullenly on a stump in front of the castle.

“Their hiding-place is in the forest,” he growled at last. “Today I tracked down a sec

ond path from the south, in addition to the path where I had watched them. Only it is up to the elbow in the quagmire. I got into the very thick of the virgin forest, but came across an impassable swamp. And I didn’t find a path to cross it. I almost drowned twice... Climbed to the top of the tallest fir-tree and saw a large glade on the other side, and in it amongst bushes and trees the roof of a large structure. And smoke. Once a horse began to neigh on that side.”

“We will have to go there,” I said.

“No. No foolishness. My people will be there. And excuse me, sir, but if we catch this lousy bunch, we’ll deal with them as with horsethieves.”

He grinned, and the grin that I saw on his face from under his long hair, was not a pleasant one.

“Muzhiks can suffer long, muzhiks can forgive, our muzhiks are holy people. But here I myself shall demand that with these... we should deal as with horse-thieves: to nail their hands and feet to the ground with aspen pegs, and then the same kind of peg, only a bigger one to stick into the anus up into the innards. And of their huts I won’t leave one live coal, we will turn everything into ashes, this rotten riffraff should never be able to set foot here again.” He thought a moment and added: “And you beware. Perhaps some day something smelling of a landlord may creep into your soul. Then the same with you... sir.”

“You’re a fool, Rygor,” I uttered coldly. “Svetilovich also belonged to the gentry, and throughout all his short life he defended you, blockheads, defended you from greedy landowners and the conceited judges. You heard, didn’t you, their lamentations, how they wailed

over him? And I can lose my life in the same way... for you. Better if you’d kept quiet if God hasn’t given you any sense.”

Rygor grinned wryly, then took out from somewhere an envelope so crumpled as if it had been pulled out from a wolf’s jaws.

“All right, don’t take offence. Here’s a letter. It lay at Svetilovich’s three days, addressed to his house... The postman said that today he brought a second one to Marsh Firs for you. So long! I’ll come tomorrow.”

Without leaving the place, I tore open the envelope. The letter was from the province from a well-known expert in local genealogy to whom I had written. And in it was the answer to one of the most important questions:

“My Highly Respected Mr. Belaretzky: I am sending you information about the person you are interested in. Nowhere in my genealogical lists, as well as in the books of old genealogical deeds did I find anything on the antiquity of the Berman-Gatzevich family. But in one old deed I came across a report not devoid of interest. It has come to light that in 1750 in the case of a certain Nemirich there is information about a Berman-Gatzevich who was sentenced to exile for dishonourable behaviour — banishment beyond borders of the former Polish Kingdom and he was deprived of his rights to aristocratic rank. This man was the step-brother of Yarash Yanowsky nicknamed Schizmatic. You must know that with the change of power old sentences lost their force, and Berman, if he is an heir of that Berman, can pretend to the name of Yanowsky if the main branch of this family vanishes. Accept my assurance...” and so on and so forth.

I stood stunned, and although it was growing dark and the letters were running before

my eyes, I kept on reading and re-reading the letter.

“Devilish doings! Now all’s clear. This Berman is a scoundrel and a refined criminal — and he is Yanowskaya’s heir.”

And suddenly it struck me:

“The hand... the hand?.. Aha! Looking at me through the window the Little Man —his hand was like Berman’s! The fingers as long as Berman’s, not the fingers of a human being.”

And I rushed off to the castle. On the way I looked into my room. But no letter there. The housekeeper said there had been a letter, it had to be there. She guiltily fawned upon me: after that night in the archive she had become very flattering and ingratiating.

“No, sir, I don’t know where the letter is. No, there was no post-mark on it... Most probably it was sent from the Yanowsky region or perhaps from a small district town. No, nobody was here, save perhaps Mr. Berman who came in here thinking that you, sir, were at home...”

I didn’t listen to her any more. I glanced at the table where papers were lying about scattered, among which someone had evidently been rummaging, and ran to the library. Nobody there, only books piled high on the table. They had evidently been left in a hurry for something else more important. Then I went to Berman’s room. And here marks of haste, the door wasn’t even locked. A faint light from my match threw a circle of light on the table, and I noticed a glove on it and an envelope torn slantingly, an envelope just like the one that Svetilovich had received that awful evening:

“Mr. Belaretzky, My Most Respected Brother: I know little about the Wild Hunt, nevertheless I can tell you something of interest about it. And in addition, I can throw some light

on a secret, and on the mystery of several dark events in your house. It may simply be a product of the imagination, but it seems to me that you are searching in the wrong place, dear brother. The danger lies in the very castle belonging to Miss Yanowskaya. If you wish to know something about the Little Man at Marsh Firs, come today at nine o’clock in the evening to the place where Roman perished and his cross lies. There your unknown well-wisher will tell you wherein the root of the fatal events lies.”

Recalling Svetilovich’s fate, I hesitated, but I had no time to lose, or to think long: the clock showed 15 minutes before nine. If Berman is the head of the Wild Hunt, and if the Little Man is his handiwork, then reading the perlustrated letter must have upset him terribly. Can it be he’s gone instead of me to meet that stranger, to shut up his mouth for him? Quite possible. And in addition, the watchman, when I asked him about Berman, pointed his hand northwest, in the direction of the road leading to Roman the Elder’s cross.

That is where I ran to. Oh! How much I ran those days, and as people would say today, got in some good training. To the devil with such training together with Marsh Firs! The night was brighter than usual. The moon was rising over the heather waste land, a moon so large and crimson, shining so heavenly, our planet’s colour so fiery and such a happy one, that a yearning for something bright and tender, bearing absolutely no resemblance to the bog or the waste land, wrung my heart. It was as if some unknown countries and cities made of molten gold had come floating to the earth and had burnt up over it, countries and cities whose life was entirely different, not at all like ours.

The moon, in the meantime having risen higher, became pale and grew smaller, and little white clouds, resembling sour milk, were covering the sky. And again all became cold, dark and mysterious: and there was nothing to be done about it, unless, perhaps, to sit down and write a ballad about an old woman on her horse with her sweetheart sitting in front of her.

Having somehow got through the park, I came onto a path and was already nearing Roman’s cross. To the left the forest made a dark wall, and near Roman’s cross loomed the figure of a man.

And then... I simply did not believe my eyes. From out of somewhere phantom horsemen appeared. They were slowly approaching that man. In complete silence. And a cold star was burning over their heads.

The next moment the loud shot of a pistol was heard. The horses began to gallop, stamping the man’s figure with their hoofs. I was astounded. I thought I should meet scoundrels, but became the witness of a killing.

Everything became dark before my eyes, and when I came to, the horsemen had vanished.

Throughout the marshes spread a frightful, inhuman cry filled with terror, anger and despair — the devil knows what else. But I felt no fright. By the way, I have never ever been afraid of anything since that time. All the most awful things that I met with after those days seemed a mere trifle in comparison.

Carefully, as a snake, I crept up to the dead body darkening in the grass. I remember that I feared an ambush, was myself thirsting to kill, that I crept on, coiling, wriggling in the autumn grass, taking advantage of every hollow, every hillock. And I also remember to this very day, how tasty was the smell of the absinthe, how the

thyme smelled, what transparent blue shadows lay on the earth. How good was life even in this awful place! But here a man had to wriggle and coil like a snake in the grass, instead of breathing freely this cold, invigorating air, watching the moon, chest straightened, walking on his hands out of sheer happiness, kissing the eyes of his beloved.

The moon was shining on the dead face of Berman. His large meek eyes were bulging, on the distorted face an expression of inhuman suffering.

But why had they killed him? And why him? Wasn’t he guilty? But I was certain that he was.

Oh! How bitter, how fragrant the smell of the thyme! Herbs, even dying, smell bitter and fragrant.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН