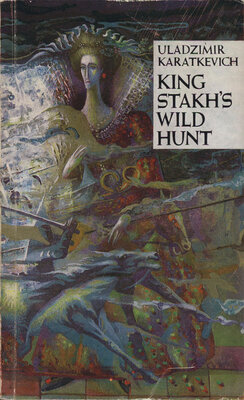

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

We were swearing: Mikhal was bandaging my head and I was screaming that it was a trifle, rubbish. Soon one man was found alive among the Hunters, and he was led to a blazing camp-fire. In front of me stood Mark Stakhevich, his hand hanging down at his side like a whip. It was that very same young aristocrat whose conversation with Patzook I had overheard sitting in the tree. He looked very colourful in his cherry-coloured chuga, in a little hat, with an empty sabre scabbard at his side.

“It seems you threatened the muzhiks, didn’t you, Stakhevich? You will die as these here,” I said calmly. “But we can let you go free, because, alone, you are not dangerous. You will depart from the Yanowsky region and will remain alive, if you tell us about all the foul deeds of your gang.”

He hesitated, looked at the severe faces of the muzhiks, the crimson light of the camp-fire lighting up their faces, their leather-coats, their hands gripping their pitchforks, and he

understood there was no mercy to be expected. Pitchforks from all sides were surrounding him, touching his body.

“Dubatowk is to blame— it’s all his doings,” he said sullenly. “Yanowskaya’s castle was to have been inherited by Garaboorda, but he was greatly in debt to Dubatowk. Nobody, except us, Dubatowk’s people, knew about that. We drank at his place and he gave us money. While himself he dreamed of the castle. He did not want to sell anything from that place, although the castle cost a lot of money. Varona said that if all the things in the castle were sold to museums, thousands could be realized. A chance event brought them together. At first Varona did not want to kill Yanowskaya even though she had refused to marry him. But after Svetilovich’t appearance, he agreed. The tale about King Stakh’s Wild Hunt came into Dubatowk’s head three years ago. Dubatowk has hidden money laid aside somewhere, although he seems to be living poorly. In general he is a liar, very sly and secretive. He can twist the cleverest man round his little finger, he can pretend to be such a bear you’d be at a loss what to think. And so he went to the best of stud farms, owned by a lord who had become impoverished in recent years, and bought all his dryckgants. Then he brought them to the Yanowsky Reserve where we built a hide-out for ourselves and a stable. Our ability to tear along through the quagmire, where nobody can even walk, surprised everybody. But nobody knows how long we crept along the Giant’s Gap in search of secret paths. And we found them. And studied them. And taught the horses. And then we dashed through places where the paths were up to the elbow in the quagmire, but at the sides — impassable marsh land. And the horses

are a miracle! They rush to Dubatowk’s call as dogs do. They sense the quagmire, and when a path breaks off, they can make enormous leaps. And we always went on the hunt only at night, when fog creeps over the land. And that’s why everyone considered us phantoms. And we always kept silent. It was risky. But what could we do: die of hunger on a tiny piece of land? And Dubatowk paid. And we were not only driving Yanowskaya to madness or death, but we even put the fear of God into those impudent serfs and taught them not to have too high an opinion of themselves. It was Dubatowk who got Garaboorda to force Kulsha to invite the little girl, because he knew that her father would be anxious about her. And we intercepted Roman on the way and seized him. Oh! And what a chase it was! — Ran away like the devil... But his horse broke a leg.”

“We know that,” I observed caustically. “By the way, Roman did give you away precisely after his death, although you didn’t believe his cries. And some days ago you still didn’t believe it when you were speaking with Patzook after Berman’s murder.”

Stakhevich was so surprised his jaw fell. I ordered him to continue relating.

“We inspired fear everywhere in the region. The farm-hands agreed to the price the owners gave. We began to live better. And we led Yanowskaya to despair. And then you appeared. Dubatowk’s bringing the portrait of Roman the Elder was no accident. If not for you, she would have gone mad within a week. Dubatowk saw that he had made a mistake. She was merry and carefree. You were dancing with her all the time: Dubatowk especially invited you when the guardian’s report on affairs was to be made, and his guardianship handed over, so that you

should become convinced she was poor. He conducted the estate well — it was, you see, to be his future estate. But'Yanowskaya’s poverty had no effect on you, and. then they decided to get you out of the way.”

“By the way,” I said, “I never had any intention of marrying her.”

Stakhevich was totally surprised.

“Well, never mind. All the same you interfered with us. She revived with you there. To be just, I must say that Dubatowk really loved Yanowskaya. He did not want to kill her, and if he could have got along without doing that, he would have willingly agreed. He respected you. He always said to us that you were a real man, only it was a pity that you didn’t agree to join us. In short, things became too complicated: we had to get rid of you and of Svetilovich who had the right to the inheritance and loved Yanowskaya. Dubatowk invited you to his place, where Varona was to challenge you to a duel. He played his part so well that no one even suspected that it was Dubatowk, not Varona, who was the instigator, and we in the meantime studied you closely, because we had to remember your face.”

“Go on,” I said.

Stakhevich hesitated, but Mikhal poked him with the pitchfork at the place from which our legs grow. Mark looked around sullenly.

“The affair with the duel turned out stupidly. Dubatowk made you drink a lot, but you didn’t get drunk. And you even turned out to be so smart that you put Varona to bed for five whole days.”

“But how could you then be in the house and chase after me at one and the same time?”

Stakhevich continued reluctantly:

“Behind Dubatowk’s farmstead others were

waiting, novices they were. At first we thought of sending them after Svetilovich, in case you were killed, but Svetilovich sat with us till the morning, while Varona was wounded. We set them off after you. Dubatowk still cannot forgive himself for setting these snivellers on your track. You’d never have escaped from us, the real Hunt. Then we thought you’d take the roadway, but you went over the waste land, and you even forced the Hunt to waste a whole hour in front of the swamp. Until the dogs fell on the scent — and it was already too late. We cannot, even now, understand how you had managed to escape from us then, you dodged us so well. But take my word for this: had we caught you, you’d have been out of luck.”

“But why did the horn blow from the side? And where are the novices now?”

Stakhevich forced himself to speak:

“One of us played the hunting-horn, he rode nearby. And the novices — here they are, lying on the ground. Previously we were fewer in number and took scarecrows with us on spare horses. We supposed that only you and Rygor were lying in wait. But we did not think there’d be an army of you. And hard did we pay for that. Here they all are: Patzook, Yan Styrovich, Pavlyuk Babayed. And even Varona. You aren’t worth even a finger-nail of his. A clever man was Varona, but he, too, has not escaped God’s judgement.”

“Why did you throw me that note saying that King Stakh’s Wild Hunt comes at night?”

“What are you saying? Phantoms don’t throw notes. We wouldn’t have done such a stupid thing.”

“Berman must have done it,” I thought, but said:

“But it was the note that convinced me you

were not phantoms, at the very moment when I had begun to believe you were. Be thankful to the unknown well-wisher, for hardly would I have been brave enough to fight with phantoms.”

Stakhevich turned pale and with lips hardly moving, he said:

“We’d have torn that person to pieces. As for you, I hate you in spite of the fact that it is beyond my power to do anything. And I’ll keep silent.”

Mikhal’s hand grabbed the prisoner by the scruff of his neck and squeezed hard.

“Speak. Otherwise all’s up with you...”

“The deuce take it, you’re the powerful ones... You can be satisfied, you serfs... But we taught you a lesson, too. Let anyone try to learn what became of those who complained most in the village of Yarki and whom Antos wiped off the face of the earth. You can ask anyone you like. It’s a pity that Dubatowk didn’t give the order to lie in wait for you in the daytime and shoot you. For that would’ve been easy to do, especially when you were on the way to the Kulshas, Belaretzky. I saw you. Even then we realized you had prepared the noose for us. Kulsha, the old woman, even though mad, could still have blurted out something. She had begun to guess that she was a tool in our hands the day of Roman’s murder. And we only had to threaten her once with the appearance of the Wild Hunt. Her head was weak, and she immediately went balmy.”

The abomination this man was telling us about made my blood boil. It was only now that my eyes were opened to what depths the gentry had fallen. And within me I agreed with Rygor that it was necessary to destroy this kind of people, that it had raised a stink across the whole world.

“Go on, you skunk!”

“When we learned that Rygor had agreed to carry out the search together with you, we realized that things would be tough for us. For the first time I saw Dubatowk frightened. His face even turned yellow. We had to stop, and not for the sake of wealth, but in order to save our own hides. And we appeared at the castle.”

“Who was it that yelled then?” I asked severely.

“He who yelled is no more. Here he lies... Patzook...”

Stakhevich was frankly amusing himself in relating everything arrogantly, with such a display of courage, as if he were about to begin to wail at any moment, alternately lowering and raising his voice. I heard the howling of the Wild Hunt for the last time: inhuman, frightening, demoniacal.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН