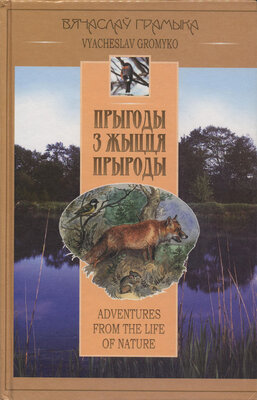

Прыгоды з жыцця прыроды

Adventures from the life of nature

Вячаслаў Грамыка

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 263с.

Мінск 2003

Really, hunting is not a fun but firing, though sporting, they do not play with weapons. Safety, while using it, should always be maintained. Any carelessness, any seemingly minor mistake is not allowed when you have to deal with weapons. Everything is important in this case, everything is the main thing without exception. With deep gratitude I remember now the words of the old forester, Yokha-Makha, that a fowling-piece is not supposed for aiming at a man, since, even unloaded, it fires once a year.

And, perhaps, also those attitudes to hunting business, which were inculcated during the hours of lectures and practice on hunting in Belovezha virgin forest by a wonderful man and teacher, Vladimir Sergeevich Romanov, warded trouble off in this particular accident.

I can't but remember this man who, when 1 was a youth already, just like Kuzmich long ago in my childhood, gave me much for understanding of life; it seems to me something was common in them. Perhaps, their love of nature, their sincere attitude towards man.

Just like Kuzmich, Vladimir Sergeevich always tried to share his knowledge and experience with those who were by his side: no matter whether they were his work colleagues at the Ministry or us, students, who came right to his office for a lecture, or foresters and workers at those places where he began his post-war working life.

We first met with Vladimir Sergeevich when I was a 5th-year student of the University, when the Dean of the Biological Faculty invited him to read the course on hunting for the group of students whose specialization was nature protection. As it was mentioned above, he read us lectures not in the University lecture hall, but in his working study, (at that time he worked as the Deputy Minister of the Republican Forestry) and this very circumstance attached particular importance to our classes and all of us took them extremely conscientiously.

He had much to tell us about. For long years Vladimir Sergeevich had been working as the Director of the Belovezha virgin forest and this influenced his behavior greatly. He was

restrained and serious, rather than strict, but good natured and solicitous at the same time. His lectures did not represent some formal collection of information, which the program required, they were delivered in the form of a natural discussion. At such moments we received that precious knowledge, which had been derived from the very life itself.

Vladimir Sergeevich lacked one leg. He never told us how that had happened and we did not dare to touch upon that subject ourselves. He used a well made artificial leg and only when walking he threw it forward quite noticeably and it became clear that the leg was not his own one. He also used a large massive cane, made of pieces of dropped horns of hoofed animals, even the upper handle of the cane had been well sorted out from a small fork of their appendix.

But we were especially lucky to learn the most valuable and useful things for our future live when he completed reading the program of the course and we had to cover the so-called practical lessons on the subject in a real hunting farm.

Then we were taken to Belovezha virgin forest for several days. They lodged us in the room of local forestry department. We immediately made friends with local workers, experts in hunting and foresters, scientific researchers and huntsmen, ordinary workers of the farm and machine operators — all those who had relation to hunting business in that region.

Talking to them, we learned in detail what an interesting and many-sided person Vladimir Sergeevich Romanov was. Here his best human qualities were revealed to us.

The first thing that surprised us was his respect toward man. We did not feel imperious notes on the part of Vladimir Sergeevich. He did not separate himself from us, his former and present subordinates, though his authority was very high and unquestionable. Naturally, when you come back to the places well known to you a great deal of impressions and recollections affect you. And no wonder that immediately after we arrived into the forest, everybody who knew and even those who did not know Vladimir Sergeevich before, but heard about him, rushed to .meet the dear guest. Rather a large company has gathered

together and the forest kitchen was at work already, preparing different hunting viands.

Everyone, somewhat inadvertently, forgot about us, students, but not Vladimir Sergeevich. When he was invited to the table, he thanked and reminded that his students stayed in the room of the inn stressing the word “his” in some special and expressive manner, as if he wanted to underline that we should not be separated from him. And then he even did not ask but rather ordered to show respect to us and right after that have been served to him appeared on our table. While dining, he was listening to those present, who told about their successes, troubles and hopes, shared with him their plans and problems. Romanov tried to help in any possible way: with a good piece of advice, an apt example or real help.

Meanwhile, we also feasted at the table with pleasure, since a student didn't always have a chance to have a nice and delicious meal.

Then some of us were relaxing lying on newly made beds after a long journey, others were sitting and admiring nature and some were breathing fresh air with delight.

One-story wooden house, which was both the forestry office and the inn at the same time, served us a shelter. For about an hour and a half I had been strolling about the forest, I was more attracted by the spring fragrance of the virgin forest. I was over three hundred kilometer away from Minsk. Spring comes here, probably, a fortnight earlier, violating all phenological terms: earlier return of birds form the south, appearance of leaves on birch trees and first nests of birds.

Gradually it got dark in the forest. I hurried back so as not to get lost. Hedgehogs got under my feet; it might be the special period of their activity. There were so many of them that I made up my mind to catch several to entertain my course mates in the morning. I caught two small horny balls, then one more, and brought them in our sleeping-room. Then I also went to bed and soon fell asleep.

We were woken up early in the morning as the hedgehogs became animated. They were sniffing strongly and stamped loudly their short strong feet on the floor.

Everybody felt like sleeping very much, but we wondered what was happening in the room. The desire to sleep conquered in the long run and awakened travelers, paying no attention to sniffing and tramping, wrapped themselves up more comfortably and pulled blankets over their heads being lazy to look what was going around.

But, the hedgehogs went on tramping and sniffing. I also felt languor still, but took an interest from under the blanket.

The oldest one from our company, Beard (his nickname) — Anatoly Kovalev — lowered his beard under the bed and started to frighten a hedgehog loudly:

“Foo-foo!”

Or:

“Froo-froo!”

I heard a hedgehog reply from under the bed:

“Foor! Foor! Top-top-top-top!”

It looked as if the animal was teasing him.

Impossible to sleep! No rest at all, but nobody had a slightest desire to leave the bed so as to drive the willful creature away. He, Anatoly, again wrapped himself up over his head trying not to pay attention to anything. Though his beard sticks out a bit, it was too big, and Anatoly rakes it up with his hand.

I was telling all this in detail to my companions on our way back to the village of Dovbeny and I noticed with pleasure how the impression of that unpleasant event was vanishing gradually.

There is hardly a man who had not heard from various sources about the Belovezha virgin forest, who had not listened to the songs devoted to it, who had not read exciting adventure stories about the life of its inhabitants. But one thing is to hear about something and quite another — to see it with your own eyes.

So, in these wild virgin forests, Vladimir Sergeevich happened to introduce proper order in post-war years, to fight against thieves, to win prestige of a leader and of a man.

At that time, much timber was being stolen. If anybody took for himself, for his building needs, there was no problem about that, but when the forest was cut barbarously, when its best reserves were wiped out and sold for profit, then Vladimir Sergeevich was not going to give up. At that time there appeared

a whole gang of criminals who used to steal trees at night, processed them at their underground sawmill and flogged timber for triple price, as they said, stripping the last skin off those who were in a bade need of it.

For a long time Valdimir Sergeevich failed to trace them. The gang was extremely cunning and experienced, they knew well both the roads and secret passages. Moreover, country folk of virgin forest farmsteads dreaded them.

But finally Romanov somehow managed to find their well camouflaged sawmill and dared to undertake an extreme measure — poured gasoline over it and burnt it to ashes.

Several days later there was a meeting. His car was stopped on a remote forest road. He got out and looked around — five men armed with rifles, two bristling dogs with them, the people were wild-looking, unshaved, angry.

“Well, you came here to introduce your orders, didn't you?” a broad square figure in quilted tarpaulin jacket hung out forward. “Then listen: either you'll leave us alone, it is our forest, we are the masters and we’ll do whatever we like, or we'll do away with you pretty quickly!”

“Got it?” the square one bellowed at him with deliberate anger.

“Well, I got it” Romanov answered calmly, even, it seemed, too calmly, because that calmness immediately put “the masters of the forest” on their guard.

“So what's it gonna be?” they asked.

And he went on:

“Though you have not taken into consideration certain circumstances.”

“What circumstances do you mean?” somebody snarled, he was standing with the dogs far behind the others.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН