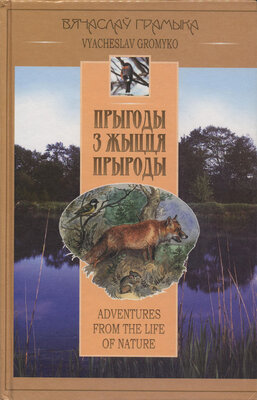

Прыгоды з жыцця прыроды

Adventures from the life of nature

Вячаслаў Грамыка

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 263с.

Мінск 2003

“I mean that not everybody can be intimidated and secondly before you met me here you should have taken interest in what I am, what I used to be and how I wield arms and it is done in the following way.”

Instantly, with one hand Romanov put his carbine from the shoulder into a combat position and fired twice from the level of his stomach.

The dogs remained lying at the place where they were sitting a moment ago.

“Altogether there are seven charges in my carbine, so, put down your guns!”

Stunned by what had happened, the thieves obeyed to his order in embarrassment.

Then Romanov, taking his carbine into the left hand, picked up thrown guns from the ground with his right hand and smashed them against a tree one by one before their very eyes.

“And I advise you not to meet me again” he concluded harshly, got into his car and drove away.

So, that's what Valdimir Sergeevich is like. He is still alive and quite recently worked in the Belarussian Technological Institute. And he taught me very much just as Kuzmich had taught me before and I always remember both Vladimir Sergeevich and Kuzmich at the same time.

Now let's get back to that distant farmstead where the old forester Kuzmich — Yokha-Makha — was spending the strained days of expectation in our family anticipating a wolf hunt.

That first night of his stay with us passed quickly, in interesting conversations. As usually, the father was sitting with reserve, smiled from time to time and again imparted serious expression, concentration on his face. We were sitting up very late that night and only when it was too dark the mother ordered:

“Well, it's time to go to bed! It's long past midnight. You'll hardly get up in the morning,” and she put the oil lamp off.

All fell asleep at once, as soon as everybody occupied gropingly the place assigned for him in the evening.

***

Everybody got up early. Obviously, the mother was the first and when the father having fed and watered the livestock and having stamped his feet in the inner porch, closed quickly the door to the hut behind him so as not to let the cold in, breakfast was ready. He and the forester took warm winter fur hats off their heads and having crossed themselves at the corner where the only icon in the hut was hanging wrapped into a clean embroidered towel, got down to the meal. We, the children, had

our breakfast always later, since there was no need for us to be in a hurry at this hour of the day. The father and Kuzmich ate quickly and immediately made for their business — the father went to the village, to the farmyard and the forester — to the woods.

It did not snow that night. Frost nipped the cheeks a little bit and Kuzmich breathed fresh air with pleasure, progressing forward leisurely.

There were lots and lots of tracks everywhere, new ones, as well as those, which remained from the last night.

In their search for food, wood inhabitants pass along many paths during the long winter night and their tracks stretch behind them.

Here a small predator ermine covered plenty of snow with drawings using its strong small paws and, in some places, with its long fluffy tail, as though it was a broom. It had spent here not a single hour, looking for mice and forest rats.

There partridges fed on the seeds of a barren, which sticks out from under the snow. It is hard to say how much they had eaten, but littered excessively. Now every beast of prey will understand they are nearby.

The forester moved several steps forward and... Well, of course, here they rose into the air in the whole flock with a peculiar fuss. They flew with ease and low, moved about one to two hundred steps and landed again among the hummocks.

And here there was a tiny trace, which could hardly be seen, as if somebody had dragged a thin lace along the snow, then the same lace stretched, like an even ribbon, at a distance of several steps and suddenly disappeared. It was a forest mouse, which got bored of sitting motionlessly in its winter house underground, came out for a minute walk and slipped back into a small and warm hole to avoid the danger of getting into sharp clutches.

The old forester was nearing the place where the bait had been left but he could not see tracks of wolves.

Clearings and coppices were densely covered with tracks of hares: more careful, round and broad, left by paws of white hare strongly trimmed with fur and with long and sweeping ones made by grey hare. The patterns of a white hare prevailed, grey

hares kept mainly close to the fields and small thickets by the dwelling of a man and only some species remains in vast forest tracts together with white hares.

Squirrels, which descended to the ground, also left traces here and there. Sometimes a lonely chain of marten's tracks — a small animal valuable for its beautiful fur — caught his eye and sometimes all this versatile constellation of chains with different sizes and shapes, left by a paw in one place, by wings or by a beak in another, was cut by the even and consistent track of a forest sly one — a vixen. It would not mind to profit by the owner of any of these patterns.

But, as before, the tracks of wolves did not catch the forester's eye. He was already close to the bait and by all that, Kuzmich felt that wolves had not appeared in the environs yet, but a guess is a guess and business is business. So he proceeded forward persistently.

Again there is an intricate web of hare's paths. Again there is an even track of a vixen and here boars had their winter party. So much soil was dug over by them! No doubt, it is not easy for boars to dig soil during the wintertime, but they do cope with it. It was seen clearly how they had been getting acorns and nuts from under the snow, even how they had been digging sappy roots out of the soil.

But, of course, the ant hill is a pitiful sight. Wild boars have not passed round it — they destroyed it getting tasty snack containing white ant larvae. It is hardly possible not to feel sorry for ants, they are very useful small insects, they guard the forest against almost all pests, but what is to be done? Needs must when the devil drives, boars have to live on something, too. Besides, hard working ants will restore their house. As soon as the first warmth comes — they will carry out restoration in a matter of days, and you will never recognize it, as if it had always been like that.

Nevertheless, the presence of boars has put Kuzmich on his guard. They are greedy for carrion, just as wolves.

So taking an all-round view and reasoning about everything what he had seen, the old forester approached the bait. He stopped and gazed at the snow attentively. There was nothing around, no tracks or other marks, which could be evidence of

wolves' recent presence here. The carcass, slightly covered with snow, was untouched as before.

Having walked round that place, the old man made his way back. After several steps he turned aside a bit and moved back from the forest taking a slightly different way to make sure whether wolves were present in the forest or not. He was walking slowly.

When he was going out to the border of the field, Kuzmich noticed a few roes in the forest. They stood at some distance keeping amidst a tall coniferous wood and looked at him alarmed.

Kuzmich loved those animals very much. He looked at them more attentively. There were five of them, a small herd, which these gracious and stately animals of our forests, a real decoration of our landscape, usually keep to in winter. Being chestnut, particularly on the neck and trunk, these animals are usually lighter in the lower part of their body. A large fair setting instead of the tail, which is almost absent and called by the hunters “the mirror”, became totally white.

Small muzzles of the roes were sniffing the smell, turning towards it and back in succession. Beautiful small heads with long mobile ears and large trustful eyes were wonderfully supplemented with thin flexible necks and neat tall legs.

A roe lives on grass and young shoots of trees. It eats up clovers, pea pods, sedge and visits plantations of winter crops in spring and fall. During the period of oats ripening it eats up oats panicles willingly. In wintertime a roe gets fodder from under the snow shoveling it aside with hoofs. Chiefly it is bilberries, cowberries, heather, sprouts of young bushes.

People's attitude towards roes is solicitous since their number has considerably reduced of late. Two moments play the decisive role in roe's life — sufficiency of fodder and presence of enemies — beast of prey. A roe itself is practically helpless. It can only save itself by running away or by hiding in the thicket. But it is an unreliable protection from such swift and strong predators as a wolf and a lynx and usually there is no rescue. In wintertime, it falls through deep snow, cuts its legs against snow's rigid crust. Only man can help a roe in such times.

Kuzmich made for roes feed-up sites every winter, put there small haystacks and besoms made of dry tree branches, which he used to prepare in advance.

What will happen if wolves suddenly do not come and the planned hunting does not succeed and then, after some time, they show up here and slaughter the deer? Quick beasts of prey will overtake them on the snow without difficulty and it is not hard for wolves to deal with them.

Thinking in that way, he came out of the forest and now was sliding on the snow more swiftly so as to reach the hamlet earlier.

On the road to the hamlet he twice came across grey hares. One of them let him approach very close when the old man was passing the edge of a graveyard. The hare was spending its daytime resting by the precipice of a vast elongated pit washed out by summer waters. It was resting and only when it heard some gritting on the snow quite near, did it leap up fearfully, made a great jump into the air and headlong rushed through bushes along the field.

He came across another one nearly by the hamlet. Raised by somebody from its bed it was jumping across the field just crosswise the road, along which Kuzmich was coming back home and it was running right towards him. The hare did not notice the man, though. It was still in the distance from him.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН