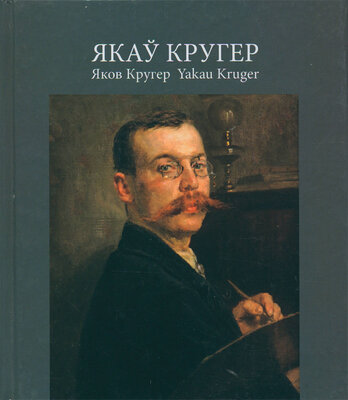

Якаў Кругер

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 74с.

Мінск 2013

In the early summer of 1915, Kruger and his family moved to Kazan for seven years, fleeing from the First World War and the riots. Only Portrait of a Girl (1918) has been preserved from that period. This is one of the most sublime, subtle and delicate pastel works of Kruger. A romantic and idealized “divine being” painted in the spirit of salon portraits of the turn of the century does not correspond to conditions of the Civil War, typhus epidemic and halfstarved existence in the evacuation. There is nothing left in it from the past sober view of the artist.

28

In the autumn of 1921, he returned to his native Minsk — already the capital of the Soviet Byelorussia. Renewal of a private school could not be even considered at the time. Kruger began to teach drawing at the workers’ faculty of the recently opened Belarusian State University in 1921. He also taught in studios. There came “the hour of triumph” for Kruger as the portrait painter in the 1920s. His role as a “stepson”, as he put it, who had sought commissions for portraits from wealthy landowners slipped into the nothingness. He was in demand more than ever and worked hard, portraying the “heroes of modern times”. Commissions followed one after the other.

From 1921 to 1922, he painted portraits of leaders, scientists, poets and national heroes on the instructions of the Peoples Commissariat of Education. Together with other artists he went to ethnographic expeditions around Belarus, making sketches of catholic and orthodox churches and synagogues (Bernardine Roman Catholic Church in Slutsk, 1921; Synagogue Cold in Minsk, 1921). At the first AllBelarusian Exhibition in 1925 Kruger also showed historical portraits with the Belarusian theme (Kastus Kalinousky and Francysk Skaryna, the First Belarusian Printer).

At the second half of the 1920s Kruger was actively involved in the design of the Museum of Revolution of the Byelorussian SSR. He painted portraits of the party and the government leaders for the museum. Besides the workers’ faculty, he taught at Minsk school number 8, worked at the art studio in a pedagogical training centre and as a painterreporter for the Belarusian newspapers.

The main theme of the turn of the 1920—30s was a large series of portraits of the Jewish intelligentsia (actor Salamon Mikhaels, writer Mendele Mocher Sforim, poet Izy Haryk, philosopher S.Y.Volfsan, Marya Gredinger) and collective farmers of the Crimean Jewish agricultural commune New Life (A Scything Peasant, First Organizer of a Collective Farm, Jewish Collective Farmer), etc.

But Kruger was never limited to the rigid framework of ethnic themes. In the same years along with portraits of the Jewish intelligentsia he painted portraits of Y. Kupala, Y. Kolas, V. Galubok, V. Ignatousky, F. Zhdanovich, M. Meleshka, etc. In many of these paintings social importance of culture figures had

29

precedence over psychological depth of the individual, although in the portrait of Yakub Kolas he tried to convey the inner world of the poet through the Belarusian characteristic landscape with small cottages and bowed birches in the background. Kruger painted his models using dull neutral backgrounds.

The portrait of Yanka Kupala is the most sincere painting in this series; it expresses good feelings of the artist to Kupala as a poet and man. The canvas was created from life in the study of the poet at a widely open window, from which was visible a morning blooming garden painted almost in an impressionistic manner. The poet was depicted with a book of poems that had made him famous — Zhaleika. Informal and even slightly sentimental air of the portrait was highlighted by small details — a cigarette in the hand of Kupala and a peony on the table.

The style of the Soviet official portrait was gradually formed in Kruger’s commissioned portraits of the end of the 1920s (the portrait of the philosopher Volfsan), which were characterized by the Belarusian art historian N. N. Shchakatsikhin as “naturalism of academic school”. The style of the Soviet ceremonial portrait would be firmly established later, when after 1934, Belarusian painters would accept the call of I. Brodsky, the chairman of the Artists’ Union of the USSR, to create a portrait gallery of “people of labour”.

In the early 1930s, when, according to Anna Akhmatova, “art was canceled” by creating a governmentcontrolled Union of Soviet Artists, Kruger’s realistic method seemed to fit perfectly into the aesthetic criteria of socialist realism, which based on the art of the Itinerants understandable to the masses. However, Kruger did not become the “father” of Belarusian socialist realism, though he entered the Organizing Committee of the Artists’ Union of the BSSR. This place was taken by others. The old master was seen only as a quite respected “fellow traveler” as it was called then. There were no necessary components of the style in Kruger’s art: party spirit, elevated glorification and revolutionary pathos. Indeed, the old master did not succeed in creating largeformat paintings about labour, but his portraits of workers (Portrait of a Strike Worker) successfully show modernity and the spirit of the 1930s in a sharp, almost OSTlike (OST —

30

Society of Easel Painters. — Aut.) style. “Contemporary themes have always interested the artist and he, in spite of his advanced years, willingly visited Minsk metal workers and workers of other plants with his box of paints, a brush and paper. And there he sat up late making studies, portraits, sketches”, later recalled Yafim Sadousky, a friend of the artist and journalist, highlighting incredible diligence of the painter, “who could not live a day without a brush in his hand”9.

The image of an old artist was accurately depicted in the selfportrait The Last Ray (1931). Kruger, who lived a long and tiring life, showed himself a significant and worthy individual. The painting was created as if in unison with his early selfportrait, where his young face was lit by the rays of the rising sun — the metaphor of the beginning of his life. At this selfportrait the last ray of the sun shines behind the 62yearold artist symbolizing the upcoming end of life. It seems that the background of the painting is divided into a dark part and a light part.

In the 1930s — the last decade of his life — he would still work a lot at “social commissions” accepting as many new conditions of existence, probably, with sincere faith in their necessity. But his best paintings would become the matter of the past. Painting of the portrait of K. E. Voroshilov, which was inexplicably created in an elegant oval from photograph, is crude and primitive. Moreover, private commissioned portraits (Portrait of Tamara Khadynskaya, 1934) became affecting and sweet. And already young Belarusian artists pointed him out “lack of a wellthought composition and deep exploration of a depicted theme”10.

His numerous portraits of Stalin of the second half of the 1930s are not only a paroxysm of officialism, but they also tried to somehow “calm” a terrible storm of repressions that swept over his yesterdays models. Persons from his portraits (V. Ignatousky, I. Haryk, A. Charvyakou, N. Galadzed, V. Galubok, G. Gai and many others) perished or left the front of the stage. But Kruger remained. Although his was constantly criticized for naturalism, illusionism, bourgeois way

9 Садовскйй E. Талант м кмсть // Советская Белоруссня. — 1969. — 18 дек.

10Я. М. Кругер // Каталог выставкм, посвяіценной 70летмю co дня рождення н 45летаю его творческой деятельностл. — Ммнск, 1939. — С. 11.

31

of thinking and lack of pathos, his career was not ruined. Any government needed a professional praising brush celebrating its heroes. It was necessary to accept new “game rules” in order to survive. Kruger accepted them without a shade of doubt. He had been a portrait painter of “the victors” who became outcasts in a decade. He walked a very difficult path from A Newspaper Boy (1907) to his last painting Stalin Listens to Report (1940) and gradually became an official portrait painter, “a veteran of Belarusian realistic painting”. Kruger was neither a discoverer of new ways in art, nor a rebel. “He was just a painter, the same as a doctor, a baker or a tailor who works regardless great politics. Kruger was faithfully fulfilling his professional duties and it was obviously his creative and life creed”11. He honestly illustrated “heroes of the time”.

Krugers personal exhibition dedicated to the 40th anniversary of his creative activity was held at the House of Artists in 1934. 49 paintings of various periods were shown there12. On November 22, 1939, Kruger was awarded the title of Honoured Artist of the BSSR and received a personal pension according to the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR “for fruitful work, dynamic pedagogical activity and training of new talents”. He became the second artist in Belarus after Y. Pen who was awarded this title by the government. The last exhibition dedicated to his 70th anniversary took place in 193912.

Until his last days Kruger, who seemed to have had a stroke at the end of the 1930s and spoke indistinctly, painted from life with young artists at the studio of the House of Artists. He became a witness of all misery and menacing changes that had befallen his generation and finished his life as an acknowledged artist. Yakau Kruger died in 1940 and was buried at the Military Cemetery in Minsk. Only nearly 30 works from his rich heritage have survived the war. They consist of paintings sent to an exhibition in Vitebsk in 1941 and also of works preserved

11 Assessment of V. V. Vaitsekhouskaya, the author of the catalogue of works and researcher of the Belarusian art of the 1920—1930s.

12 Я. M. Кругер. Заслуженный деятель яскусств БССР // Каталог выставкл, посвяіценной 70летпю co дня рождення н 45летмю его творческой деятельностм / вст. ст. Н. Дучмц н Н. Тараспкова. — Мпнск, 1939. — С. 11.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН