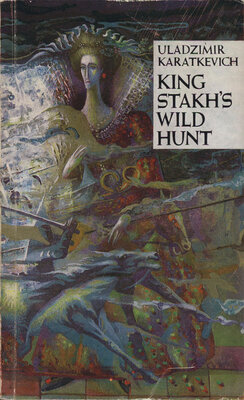

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

I do not know whether this gathering of the gentry is worth describing. You will find a good and quite a correct description of something like it in the poetic works of Phelka from Rukshanitzy, an unreasonably forgotten poet. My God, what carriages there were! Their leather warped by age, springs altogether lacking, wheels two metres high, but by all means

at the back a footman (footmen’s hands were black from the earth they worked on). And their horses! Rocinant beside them would have seemed Bucephalo. Their lower lips hanging down like a pan, their teeth eaten away. The harnesses almost entirely of ropes, but to make up for that here and there shone golden plates with numbers on them, plates that had been passed on from harnesses of the “Golden Age”.

“Goodness gracious! What is going on in this world? Long ago one gentleman rode on six horses, while now six gentlemen on one horse.” The entire process of the ruin of the gentry was put into a nut-shell in this mocking popular saying.

Behind my back Berman-Gatzevich was making polite but caustic remarks about the arriving guests.

“Just look, what a fury (in the Byelorussian of the 16th century a jade was called a fury). Most likely one of the Sas’ rode on her: a merited fighting horse... And this little Miss, you see how dressed up she is: as if for St. Anthony’s holiday. And here, look at them, the gypsies.”

It was really an unusual company that he called “gypsies”. A most ordinary cart had rolled up to the entrance, in it there sat the strangest company I had ever seen. There were both ladies and gentlemen there, about ten of them, dressed gaudily and poorly. They were seated in the cart crowded like gypsies. And curtains were stretched on four sticks as on gypsy carts. Only the dogs running under the cart were lacking. This was the poor Grytzkevich family roaming from one ball to another, feeding themselves mainly in this way. They

were distant relatives of the Yanowskys. And these were the descendants of the “crimson lord”! My God, what you punish people for!

Then there arrived some middle-aged lady in a very rich antique rather shabby velvet dress, accompanied by a young man as thin as a whip, clearly fawning upon her. This “whip” of a fellow gently pressed her elbow.

The perfume the lady used was so bad that Berman began to sneeze as soon as she entered the hall. And it seemed to me that, together with her, someone had brought into the room a large sack of hoopoes and left it there for the people to enjoy. The lady spoke with a real French accent, an accent, as is known, that has remained in the world in two places only: in the Paris salons and in the backwaters of Kabylyany near Orsha.

And the other guests were also very curious people. Faces either wrinkled or too smooth, eyes full of pleading, worried, devouring eyes, eyes with a touch of madness. One dandy had extremely large, bulging eyes like those of the salamanders in subterranean lakes. From behind the door I watched the ceremony of introductions. (Some of these close neighbours had never seen one another, and probably never would again in the future.)

Sounds reached me badly, for in the hall the orchestra was already piping away, an orchestra that consisted of eight invalids of the Battle of Poltava. I saw oily faces that gallantly smiled, saw lips that reached the mistress’ hand. When they bent down, the light fell on them from the top, and their noses seemed surprisingly long while their mouths seemed to have vanished. They shuffled their feet without making a sound and bowed, spoke noiselessly, then smiled

and floated off, and new ones came floating over to take their place. This was like an awful dream.

They grinned and it was as if they were apparitions from the graves, they kissed her hand (it seemed to me that they were sucking the blood out of her) and noiselessly floated on. She was so pure in her low-necked dress, but her back reddened when some newly-arriven Don Juan in close-fitting trousers showed too great an ardour as he pressed her hand. These kisses, it seemed to me, smeared her hand with something sticky and filthy.

And only now did I realize how solitary she was, not only in her own house, but also in the midst of this crowd.

“What does this remind me of?” I thought. “Aha, Pushkin’s Tatyana among the monsters in the hut. Closed round her, poor girl, as round a doe during a hunt.”

Almost no pure looks to be seen here, but to make up for it what names! It seemed as if I were sitting in an archive and was reading ancient documents of some Court of Acts and Pleas.

“Mr. Saava Matfeyevich Stakhowsky and sons,” the lackey announced.

“Mrs. Agatha Yurevna Falendysh-Khobalyeva with her husband and friends.”

“Mr. Yakub Barbare Garaboorda.”

“Mr. Matzei Mustaphavich Asanovich.”

“Mrs. Anna Avramovich-Basatzkaya and daughter.”

And Berman, standing behind me, was passing remarks.

For the first time in these days I liked him, so much malice was there in his utterances, with

what blazing eyes he met each newly arrived guest, and especially the young ones.

But then there was a flash in his eyes that I couldn’t understand. I involuntarily looked in that direction, and my eyes nearly popped out of my head, such a strange sight did I see. Down the steps into the hall a person came rolling, that’s right, “rolling”, no other word for it. The man was over two metres in height, approximately like myself, but three Andrei Belaretzkys would have fitted into his clothes. A tremendous abdomen, the lower legs like the thighs, as if they were hams, an incredibly broad chest, palms like tubs. Few such giants had ever come my way. Though this was not the most surprising thing. The clothes he was wearing can be seen today only in a museum: red, high-heeled horseshoed boots (our ancestors called them “kabtsi”), tight-fitting trousers made of a thin cloth. The caftan made of cherrycoloured gold cloth ready to split on his chest and abdomen! This giant had pulled over it a “chuga”, an ancient Byelorussian coat. The chuga hung loosely in pretty folds and the designs in it were green, gold and black, and a bright Turkish shawl was tied around it almost up to the man’s arm-pits.

And on top of all this sat a surprisingly small head for such a body. His cheeks were puffed as if the man was about to burst out laughing. His long grey hair gave a roundness to his head, his grey eyes were very small, and his long dark whiskers — they had very few grey hairs in them,— reached down to his chest. The appearance of this man was a most peaceful one, but from his left hand hung a “karbach”..a thick, short lash with a silver wire at its end.

In a word, a provincial bear, a merry fellow

and a drunkard — this was immediately apparent.

While yet at the door he began to laugh, in such a robust, merry bass voice, that I involuntarily smiled. He walked, and people stepped aside to make way for him, answering him with smiles, such smiles that could have appeared on the sour faces of these people of caste only because they, evidently, loved him. “At last, at least one representative of the good old century,” I thought. “Not a degenerate, not a madman who could as well commit a crime as a heroic deed. And how rich his Byelorussian is and how beautifully he speaks it!”.

Don’t let this last thought surprise you. Although Byelorussian was spoken among the petty gentry at this time, the gentry of that stratum of society that this gentleman apparently belonged to did not know the language: among the guests no more than a dozen spoke the language of Martzinkevich and Karatynsky, the language of the rest was a mixture of Polish, Russian and Byelorussian.

But out of the mouth of this one, while he was walking from the door to the hall on the upper floor, poured apt little words, jokes, and' sayings as out of the mouth of any village match-maker. I must confess that he captured me at first sight. Such a colourful person he was that I did not immediately notice his companion, although he also deserved attention. Imagine for yourself a young man, tall, very well-built, and what was rare in this remote corner, dressed in the latest fashion. He would have been handsome were it not for his excessive paleness, sunken cheeks, and an inexplicable expression of animosity that lay on his

compressed lips. In his face it was his large eyes with their watery lustre that deserved the greatest attention. Set in a handsome though bilious face they were so lifeless that it made me shiver. Lazarus, when he was risen from the dead, probably had just such eyes.

In the meantime the giant had come up to an old lackey, a man somewhat blind and deaf, and suddenly jerked him by the shoulder.

The lackey had been napping on his feet, but he immediately pulled himself together, and taking in who the new guests were, smiled broadly and shouted:

“The most honourable gentleman, Gryn Dubatowk! Mr. Ahlyes Varona!”

“A very good evening to you, gentlemen,” Dubatowk roared. “Why so sad, like mice under a hat? No matter, we’ll make you merry in a jiffy. Varona, what little ladies! I was born too early. Oh! What beauties-cuties!”

He walked through the crowd (Varona had stopped near a young lady), and he approached Nadzeya Yanowskaya. His eyes narrowed and began to sparkle with laughter.

“A good day to you and good evening, my dear!” And gave her a smacking kiss on her forehead. Then he stepped back. “And how slender, how graceful and beautiful you’ve become! All Byelorussia will lie at your feet! And may Lucifer carry tar on my back in the next world, if I, an old sinner, won’t be drinking a toast to you from the little slipper in a month from now at your wedding. Only your little eyes are somewhat sad. But no matter. I’ll make you merry right away.”

And with the fascinating grace of a bear he turned round on his heels.

“Anton, you devil! Grishka and Pyatrus! Has the cholera got you, or what?”

And there appeared Anton, Grishka and Pyatrus, bending under the weight of some enormous bundles.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН