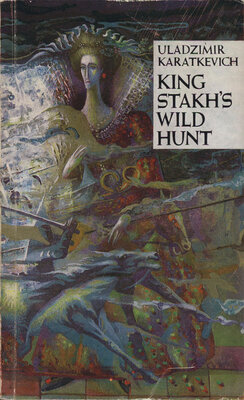

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

His face softened, became thoughtful.

“And anyway, this is all foolishness. All these heraldic entanglements, the small princes, the entailed estates of magnates. Were it up to me I would empty my veins of all this magnate blood. It only causes my conscience to suffer deeply. I think Nadzeya feels the same.”

“But I was told that Miss Nadzeya is the only one of the Yanowskys.”

“That’s really so, yes. I am a very distant relative, and also, I was thought to be dead. It’s five years since I’ve visited Marsh Firs, and now I’m 23. My father sent me away because at the age of 18 I was dying of love for a thirteenyear old girl. As a matter of fact that was unimportant, we’d have had to wait only two years, but my father believed in the power of the ancient curse.”

“Well, did the banishment help you?” I asked.

“Not a bit. Moreover, two meetings were sufficient for me to understand that the former adoration had grown into love.”

“And how does Nadzeya Yanowskaya feel?” I asked.

He blushed so that tears even welled up in his eyes.

“Oh!... You’ve guessed! I beg you to keep silent about that. The thing is that I don’t know yet what she thinks about it. And that is not so important. Believe me... It’s simply that I feel so well in her presence, and even should she be

indifferent — believe me — life would still be a good and happy thing: she will still be living on this land, won’t she? She is an unusual person. She is an extraordinary being. She is surrounded by such a dirty world of pigs, by such undisguised slavery, while she is so pure and kind.”

This youth with his clear and kind face awakened such an unexpected tender emotion within me that I smiled, but he, apparently, took my smile for a sneer.

“So you, too, are laughing at me as did my deceased father, as did Uncle Dubatowk...”

“I don’t think they were laughing at you, Andrei. On the contrary, it is pleasant for me to hear these words from you. You are a decent and kind person. Only perhaps you shouldn’t tell anybody else about this. Now you’ve mentioned the name of Dubatowk...”

“I am grateful to you for your kind words. However, you didn’t really think, did you, that I could’ve spoken about it with anybody else? You guessed it yourself. And Uncle Dubatowk — he too, did, though I don’t know why.”

“It’s well that it was Dubatowk who guessed it, not Ahlyes Varona,” I said. “It would otherwise have ended badly for one of you. Dubatowk is the guardian, interested in Nadzeya’s finding a good husband. And it seems to me that he will not tell anybody else, and neither will I. But, in general, you should not mention it to anybody.”

“That’s true,” he answered guiltily. “I hadn’t thought that even the slightest hint might harm Miss Nadzeya. And you are right — what a good man Dubatowk is and how sincere! People like him. A fine swordsman, simple and patriarchal! And so frank and merry! How he loves

people and doesn’t interfere with anybody’s life And his language! When I first heard it, it was as if a warm hand were stroking my heart.”

His eyes even became moist, so well did he love Dubatowk.

“Now you know, Mr. Belaretzky, but no one else will. And I will never compromise her. I shall be dumb. Look, you have been dancing with her, and it makes me happy. She is talking with someone — it makes me happy, if only it makes her happy. But to tell you the truth, to be frank with you...” His voice became stronger, his face like the young David’s coming out to fight Goliath. “Were I at the other end of the world and my heart felt that someone intended to hurt her, I’d come flying over, and were it God Himself, I would break His head for Him, I would bite Him, would fight to my last breath, and then I would crawl up to her feet and breathe my last. Believe me. And even when I am far away I am always with her.”

Looking at his face, I understood why the powers that be fear such slender, pure and honest young men. They have, of course, wide eyes, a childish smile, a youngster’s weak hands, a proud and shapely neck as if made of marble, as if it were especially created for the hangman’s pole-axe, but in addition to all this, they are uncompromising, conscientious even unto trifles: they are unable to accept the superiority of crude strength, and their faith in the truth is fanatic. They are inexperienced in life, are trusting children right into their old age, in serving the truth they are bitter, ironic, faithful to the end, wise and unbending. Mean people fear them even when they haven’t yet begun to act, and governed by their inherent instincts, always poison them. This base trash knows that

they, these young men, are the greatest threat to their existence.

I understood that were a gun put into the hands of such a man, he would with that sincere smile of white teeth, come up to the tyrant, put a bullet into him and then calmly say to death: “Come here!” He will undergo the greatest suffering and if he doesn’t die in prison of his thirst for freedom, he will come up calmly to the scaffold.

So boundless was the faith which this man called forth in me, that our hands met in a strong handshake and my smile was a friendly one.

“Why were you expelled?”

“Oh, some nonsense. It began when we decided to honour the memory of Shevchenko. Wc were threatened that the police would be brought into the university.” He even began to blush. “Well, we rebelled. And I shouted that if they only dared to do that with our sacred walls, we would wash that shame off them with our blood, and the first bullet would strike the man who had given that order. Then it became noisy and I was grabbed. And in the policestation, when I was asked my nationality, I answered: “Write — Ukrainian.”

“Well said.”

“I know it was very imprudent for those who had taken up the struggle.”

“No, that was good for them, too. One such answer is worth dozens of bullets. And it signifies that everybody is fighting a common enemy. There is no difference between the Byelorussian and the Ukrainian if the lash is held over them.”

We looked at the dancers silently until Svetilovich winced.

“Dancing. The devil knows what it’s like.

A waxworks show of some kind... antedeluvian pangolins. In profile not faces but ugly mugs. Brains the size of a thimble, and paws like a dinosaur’s with 700 teeth. And their dresses with trains. And the frightening faces of these curs... We are after all an unfortunate people, Mr. Belaretzky.”

“Why?”

“We have never had any really great thinkers among us.”

“Perhaps it’s better so,” I said.

“And nevertheless we are a people without a land to settle on. This infamous trade of one’s country over a period of seven centuries. In the beginning it was sold to Lithuania, then, before the people had hardly become assimilated, to the Poles, to everybody and anybody, regardless of honour and conscience.”

The dancers began to cast glances at us.

“You see, they are looking at us. When a person’s soul is screaming, they don’t like it. They all belong to one gang here. They trample on the little ones, they repudiate honour, sell their young daughters to old men. You see that one over there — Saava Stakhowsky? — I would not put a horse into the same stable with him, for the horse’s morals would be endangered. And this Khobalyeva, a provincial Messalina. And this one, Asanovich, drove a serf’s daughter into her grave. Now he can’t do that, hasn’t got the right to, but all the same he continues to lead a dissolute life. Unfortunate Byelorussia! A kind, complaisant, romantic people in the hands of rascals. And so it will always be while this nation allows itself to be made a fool of. It gives up its heroes to the rack and itself sits in a cage over a bowl of potatoes or turnips, looking blank, and understanding nothing.

Much would I pay the man who at last shook off from his people’s neck this decaying gentry, these stupid parvenues, these conceited upstarts and corrupt journalists, and made the people become masters of their own fate. For that I would give all my blood.”

Apparently my senses had become very sharp: all the time I felt somebody’s look on my back. When Svetilovich had finished, I turned around and was stupified. Standing behind us was Nadzeya Yanowskaya, and she had heard everything. But it was not she, it was a dream, a forest sprite, a being out of a fairy-tale. Her dress was like that worn by women in the Middle Ages: no less than 50 lengths of Orsha golden satin had gone into its making. And this dress had over it another, a white one, with free designs in blue that seemed as if of silver as the colours played in the numerous cuts hanging from the sleeves and the hem of the dress. Her tightly tied waist was bound by a thin golden cord falling almost to the floor in two tassels. On her shoulders was a thin “robok” made of a white and silver tinted cloth. Her hair was gathered in a net, an ancient head-dress reminding one somehow of a little ship woven from silver threads. From both hornlets of this little ship a thin white veil hung down to the very floor.

This was a Swan-Queen, the mistress of an amber palace, in a word, the devil alone knows what, but only not the previous ugly duckling. I saw Dubatowk’s eyes popping out of his head, his jaws sagging: he, too, had evidently not expected such an effect. The violin screamed. Silence fell.

This attire was quite uncomfortable and it usually fetters the movement of a woman unac

customed to it, makes her heavy and baggy, but this girl was like a queen in it, as if she had all her life worn only such clothing: her head proudly thrown back, she floated dignified and womanly. From under her veil her large eyes smiled archly and proudly, stirred by a feeling of her own beauty.

Dubatowk grunted even, so surprised was he, and he came up to her with quickening steps. With an incomprehensible expression of pain in his eyes, he took her face in the palms of his hands and kissed her on the forehead, muttering something like “such beauty”.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН