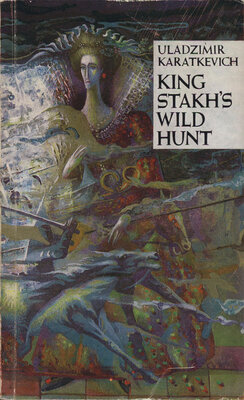

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

We kept silent. Now all depended on our self-control.

A flash lit up the room. Varona’s nerves had failed him. The bullet whizzed past somewhere to the left of me and rattled against the wall. I could have fired at this very moment, for during the flash I saw where Varona was. But I did not shoot. I only felt the place where the bullet had struck. I don’t know why I did that. And I remained standing in the very same place.

Varona, evidently, could not even have supposed that I’d twice act in the same way. I could hear his excited hoarse breathing.

Varona’s second shot resounded. And again I did not shoot. However, I no longer had the will-power to stand motionless, all the more so because I heard Varona beginning to steal along the wall in my direction.

My nerves gave way, I also began to move carefully. The darkness looked at me with the barrels of a thousand pistols. There might be a barrel at any step, I could stumble on it with my belly, all the more so that I had lost the whereabouts of my enemy and couldn’t say where the door was and where the wall.

I stood still and listened. At this moment something forced me to throw myself down sidewards on the floor.

A shot rang right over my head, it even seemed that the hair on my head had been moved by it.

But I still had three bullets. For a moment a wild feeling of gladness took hold of me, but I remembered the fragile human neck and lowered my pistol.

“What’s going on there with you?” a voice sounded behind the door. “Only one of you fired. Has anyone been killed, or not? Fire quickly, stop messing about.”

And then I raised my hand with the pistol, moved it away from the place where Varona had been at the time of the third shot and pressed the trigger. I had to fire at least once, I had to use up at least one bullet. In answer, entirely unexpectedly, a faint groan was heard and the sound of a body falling.

“Quick, over here!” I shouted. “Quick! To my aid! It seems I’ve killed him!”

A blinding yellow stream of light fell on the floor. When people came into the room, I saw Varona lying stretched out motionless on the floor, his face turned upward. I ran up to him, raised his head. My hands touched something warm and sticky. Varona’s face became even yellower.

“Varona! Varona! Wake up! Wake up!”

Dubatowk, gloomy and severe, came floating from somewhere, as if from out of a fog. He began fussing over the body lying there, then looked into my eyes and burst out laughing. It seemed to me I had gone mad. I got up and, almost unconscious, took out the second gun from my pocket. The thought crossed my mind that it was very simple to put it at my temple and...

“No more! I can’t take any more!”

“Well, but why? What’s wrong, young man?” I heard Dubatowk’s voice. “It wasn’t you who insulted him. He wanted to bring disgrace on

both you and me. You have two more shots yet. Just look how upset you are! It’s all because you’re not used to it, because your hands are clean, because you have a conscientious heart. Well, well... but you haven’t killed him, not at all. He’s been deafened, that’s all, like a bull at the slaughter. Look how cleverly you’ve done him. Shot off a piece of his ear and also ripped off a piece of the skin on his head. No matter, a week or so in bed and he’ll be better.”

“I don’t need your two shots! I don’t want them!” I screamed like a baby, and almost stamped my feet. “I give them to him as a gift!”

My second and some other gentleman whose entire face consisted of an enormous turned-up nose and unshaven chin carried him off somewhere.

“He can have these two shots for himself!”

Only now did I understand what an awful thing it is to kill a person. Better, probably, just to give up the ghost yourself. And not because I was such a saint. Quite another thing if it’s a skirmish, in battle, in a burst of fury. While here a dark room and a man who is hiding from you as a rat from a fox-terrier. I fired both pistols right at the wall, threw them down on the ground and left.

After some time, when I entered the room in which the quarrel had taken place, I found the company sitting at table again.

Varona had been put to bed in one of the distant rooms under the care of Dubatowk’s relatives. I wanted to go home immediately, but they would not let me. Dubatowk seated me at his side and said: “It’s alright, young man. It’s only nerves that are to blame. He’s alive. He’ll get well. What else do you need? And now he’ll know how to behave when he meets

real people. Here — drink this... One thing I must say to you, you are a man worthy of the gentry. To be so devilishly cunning, and to wait so courageously for all the three shots — not everyone is able to do that. And it is well that you are so noble — you could have killed him with the two remaining bullets, but you didn’t do that. Now my house to its very last cross is grateful to you.”

“But nevertheless it’s bad,” said one of the gentlemen. “Such self-control — it’s simply not human.”

Dubatowk shook his head.

“Varona’s to blame, the pig. He picked the quarrel himself, the drunken fool. Who else, besides him, would have thought of screaming about money? You must have heard that he proposed to Nadzeya, and got a refusal for an answer. I’m sure that Mr. Andrei is better provided for than the Yanowskys are. He has a head on his shoulders, has work and hands, while the last of their family, a woman,— has an entailed estate where one can sit like a dog in the manger and die of hunger sitting on a trunk full of money.”

And he turned to everybody:

“Gentlemen, I depend upon your honour. It seems to me that we should keep silent about what’s happened. It does no credit to Varona — to the devil with him, he deserves penal servitude, but neither does it do any credit to you or the girl whose name this fool allowed himself to utter in drunken prattle... Well, and the more so to me. The only one who behaved like a man is Mr. Belaretzky, and he, as a true gentleman, will not talk indiscreetly.”

Everybody agreed. And the guests, apparently, could hold their tongues, for nobody in

the district uttered a word about this incident.

When I was leaving, Dubatowk detained me on the porch:

“Shall I give you a horse, Andrei?”

I was a good horseman, but now I wanted to take a walk and come to myself somewhat after all the events that had taken place. Therefore I refused.

“Well, as you like...”

I took my way home through the heather waste land. It was already the dead of night, the moon was hidden behind the clouds, a kind of sickly-grey light flooded the waste land. Gusts of wind sometimes rustled the dry heather and then complete silence. Enormous stones stood here and there along the road. A gloomy road it was. The shadows cast by the stones covered the ground. Everything all around was dark and depressing. Sleep was stealing on me and the thought frightened me that a long road lay ahead: to go round the park, past the Giant’s Gap. Perhaps better to take the short cut again across the waste land and look for the secret hole in the fence?

I turned off the road and almost immediately fell into deep mud; I was covered with dirt, got out onto a dry place, and then again got into dirt and finally came up against a long and narrow bog. Cursing myself for having taken this roundabout way, I turned to the left to the undergrowth on the river bank (I knew that dry land had to be there, because a river usually dries the earth along its banks), I soon came out again onto the same path along which I had walked on my way to Dubatowk’s place, and finding myself half a mile away from his house, walked off along the undergrowth in the direction of Marsh Firs. Ahead, about a mile

and a half away, the park was already visible, when some incomprehensible presentiment forced me to stop ■— maybe it was my nerves strung to such a high pitch this evening by the drinking and the danger, or perhaps it was some sixth sense that prompted me that I was not alone in the plain.

I didn’t know what it was, but I was certain that it was yet far away. I hastened my steps and soon rounded the tongue of the bog into which I had just a while ago crept and which blocked the way. It turned out that directly in front of me, less than a mile away, was the Marsh Firs Park. The marsh hollow, about ten metres wide, separated me from the place where I had been about forty minutes ago and where I had fallen into the mud. Behind the hollow lay the waste land, equally lit by the same flickering light, and behind that — the road. Turning around, I saw far to the right a light twinkling in Dubatowk’s house, peaceful and rosy; and to the left, also far away, behind the waste land the wall of the Yanowsky Forest Reserve was visible. It was at a great distance, bordering the waste land and the swamp.

I stood and listened, although an uneasy feeling prompted me that IT was nearer. But I did not want to believe this presentiment: there had to be some real reason for such an emotional state. I saw nothing suspicious, heard nothing. What then could it have been, this signal, where had it come from? I lay down on the ground, pressed my ear to it, and felt an even vibration. I cannot say that I am a very bold person, it may be that my instinct of selfpreservation is more highly developed than in others, but I have always been very inquisitive. I decided to wait and was soon rewarded.

From the side of the forest some dark mass came moving very swiftly through the waste land. At first I could not guess what it was. Then I heard a gentle and smooth clatter of horses’ hoofs. The heather rustled. Then everything disappeared, the mass had perhaps gone down into some hollow, and when it reappeared — the clattering was lost. It raced on noiselessly, as if it were floating in the air, coming nearer and nearer all the time. Yet another instant and my whole body moved ahead. Among the waves of the hardly transparent fog, horsemen’s silhouettes could be seen galloping at a mad pace, the horses’ manes whirling in the wind. I began to count them and counted up to twenty. At their head galloped the twentyfirst. I still had my doubts, but here the wind brought from somewhere far away the sound of a hunting-horn. A cold, dry frost ran down my spine giving me the shivers.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН