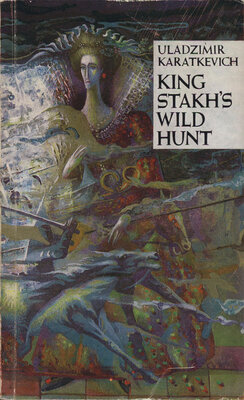

King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Уладзімір Караткевіч

Выдавец: Мастацкая літаратура

Памер: 248с.

Мінск 1989

“Well, you louts and lubbards, place everything at the feet of the mistress. Unroll it! You rascals! Your hands, where do they grow from? Not your back? Take it, daughter!”

On the floor in front of Yanowskay lay an enormous fluffy carpet.

“Keep it, my dear. It was your grandfather’s, but it hasn’t been used at all. You’ll put it in your bedroom. The wind comes in there, and the feet of all the Yanowskys are weak ones. It was a mistake, Nadzeyka, not to have come to live with me two years ago. I begged you to, but you wouldn’t argee. Well, be that as it may, too late now, you have grown up. And now things will be easier for me. To the devil with this guardianship.”

“Forgive me, dear uncle,” Yanowskaya said quietly, touched by her guardian’s attention. “You know that I wanted to be where my father...”

“Well — well — well,” Dubatowk said, embarrassed. “Let it be. I myself hardly ever came to see you, knowing that you would be upset. We were friends with Roman. But no matter, my dear, we are, of course, worldly people. We suffer from overeating and too much drinking; however, God must look into people’s souls. And if he does, then Roman, although he was wont to pass the church by but not the tavern, has already long been listening to the angels in heaven, and is looking into the eyes of his poor wife, my cousin. God — He’s nobody’s fool. The main thing is one’s conscience, whereas that

hole in one’s mouth that asks for a glass of vodka is a vile thing. And they look at you from heaven and your mother does not regret that she gave life to you at the price of her own: such a queen have you become. And you'll soon be getting married. From the hands of your guardian into the fond and strong hands of a husband. Well, what do you think?”

“I hadn’t thought of it before, and, now I don’t know,” Yanowskaya suddenly said.

“Well, well,” becoming serious, said Dubatowk. “But... the man should be a good one. Don’t be in a hurry. And now another present... It is an old costume of our country, a real one. Not some kind of an imitation. Afterwards go and change your dress before the dances. There’s no point in wearing all this modern stuff.”

“It will hardly suit her, and will only spoil her appearance,” put in some young miss of the petty gentry, trying to be flattering.

“And you keep quiet, my dear. I know what I am doing,” growled Dubatowk. “Well, Nadzeyka, and the last thing. I thought long and hard about whether to give this to you, but I am not accustomed to having what does not belong to me. This is yours. Among your portraits one is missing. The row of ancestors must not be broken. You know that yourself, because you belong to the most ancient of all the families in the whole province.”

On the floor, freed of the white cloth covering it, stood a very old, unusual portrait, the work, apparently, of an Italian painter, a portrait which you can hardly find in the Byelorussian iconography of the 17th century. There was no flat wall in the background, no coat-of-arms hung on it. There was a window opening into

the evening marsh, there was a gloomy day overhead, and there was a man sitting with his back to all this. An indefinite greyish blue light shone on his thin face, on the fingers of his hands, on his black and golden clothes.

The face of this man was more alive than that of any living man, and it was so surprisingly dismal and hard that it was frightening. Shadows lay in the eye-sockets and a nerve even seemed to quiver in the eyelids. And there was a family likeness between his face and that of the mistress, but all that was pleasant and nice in Yanowskaya, was repulsive and terrible here. Treachery, cunning, symptoms of madness, an obdurate imperiousness, an impatient fanaticism, a sadistic cruelty could be read in this face. I stepped aside — the large eyes that seemed to read the very depths of my soul turned and again looked me in the face.

Someone sighed.

“Roman the Elder,” Dubatowk said in a muffled voice, but it had already occurred to me who it was, so correctly had I imagined him from the words of the legend. I had guessed this was the one who was guilty of the curse, because the face of our mistress had become pale and she swayed back slightly.

I don’t know how this deathly-still scene would have ended, but someone silently and disrespectfully pushed me in the chest. Involuntarily I recoiled. It was Varona making his way through the crowd, and in making his way to Yanowskaya, he had pushed me aside. Calmly he continued walking without begging my pardon, he didn’t even turn round, as if an inanimate object were standing in my place.

I was born in a family of ordinary intellectuals, the intelligentsia who from generation to

generation had served the Polish gentry, who were themselves learned men, but plebians, from the point of view of this arrogant aristocrat, a man whose forefather was the whipperin of a wealthy magnate, a murderer. I had often had to defend my dignity against such, and now all my “plebian” pride bristled.

“Sir,” I said loudly. ’’You can consider it worthy of a true aristocrat to push a person aside without begging his pardon?”

He turned round.

“You are addressing me?”

“You,” I calmly answered. “A true aristocrat is a gentleman.”

He came up to me and began scrutinizing me with curiosity.

“H’m,” he said. “Who is going to teach a gentleman the rules of good behaviour?”

“I don’t know,” I answered, just as calmly and as bitingly. “At any rate, not you. An uneducated priest must not teach others Latin — nothing will come of it.”

I saw, over his shoulder, Nadzeya Yanowskaya’s face, and was happy to notice that our quarrel had diverted her attention from the portrait. The blood had returned to her face, but in her eyes there flashed something resembling alarm and fear.

“Choose your expressions carefully,” Varona said in a strained voice.

“Why? And most importantly, for whom? A well-bred man knows that in the company of polite people one should be polite, while in the company of rude fellows, the greatest degree of politeness is to repay in the same coin.”

Varona was apparently unaccustomed to being repulsed. I knew such arrogant turkey

cocks. He was surprised, but then glanced at the hostess, turned towards me again, and a turbid fury flashed in his eyes.

“But do you know with whom you are talking?”

“With whom? Not with God Himself?”

I saw Dubatowk appear at the side of the hostess. His face showed that he had become interested. Varona began to boil.

_ “You are speaking with me, with a man who is in the habit of pulling parvenues by the ear.”

“But hasn’t it occurred to you that some parvenues are themselves capable of pulling your ears? And don’t come up closer, otherwise, I warn you, not a single gentleman will receive such an insult, as you from me.”

“A caddish fist fight!” he exploded.

“Can’t be helped!” I said coldly. “I have met noblemen on whom nothing else had any effect. They weren’t cads, their ancestors were long-serving hound-keepers, whippers-in, ladies’ men for the widows of magnates.”

I intercepted his hand and held it as with a nipper.

“Well...”

“Damn you!” he hissed.

“Gentlemen, gentlemen, calm yourselves,” Yanowskaya exclaimed, alarmed beyond expression. Mr. Belaretzky, don’t, don’t! Mr. Varona, for shame!”

Evidently, Dubatowk also understood it was time to interfere. He came up, stood between us, and put a heavy hand on Varona’s shoulder. His face was red.

“You pup!” he shouted. “And this is a Byelorussian, an aristocrat? To insult a guest in such a way! A disgrace to my grey hair. Don’t you see whom you are picking a fight with? He is

not one of our chicken-hearted fools. This is not a chick, this is a man. And he will quickly tear off your moustache for you. You are a nobleman, sir?”

“A nobleman.”

“So you see, the gentleman is an aristocrat. If you must have a talk together you can find a common language. This man is an aristocrat and a good one, too; his forefathers and ours may have been friends. Do not compare him to the modern snivellers. Ask your hostess to forgive you. You hear me?”

Varona was as if a changed man. He muttered some words and walked aside with Dubatowk. I remained with Yanowskaya.

“My God, Mr. Andrei, I was so frightened for you. You’re too good a person to have anything to do with him.”

I raised my eyes. Dubatowk stood nearby and curiously looked at me and then at Miss Yanowskaya.

“Miss Nadzeya,” I said with a warmth I hadn’t myself expected. “I am very grateful to you, you are a kind and sincere person, and your concern for me, your goodwill, I shall long remember. It can’t be helped, but my pride — the only thing I have,— I never allow anybody to tread on.”

“So you see,” she lowered her eyes. “You are not at all like them. Many of these highborn people would have given in. Evidently, you are the real gentleman here, while they only pretend to be gentlemen... But remember, I have great fear for you. This man is dangerous, he’s a man with a dreadful reputation.”

“I know that,” I answered jokingly. “The local ‘aurochs’...”

“Don’t joke about it. He is a well-known

brawler among us and a rabid duellist. He has killed seven men in duels. And it is perhaps worse for you that I am standing beside you. You understand me?”

I did not at all like this feminine dwarf with her large sad eyes. Her relations with Varona held no interest for me whatsoever, whether he was a sweetheart or a rejected admirer. However, one good deed deserves another. So sweet was she in her care for me, that I took her hand and carried it to my lips.

“My thanks, mademoiselle.”

She did not remove her hand, and her transparent gentle little fingers slightly trembled under my lips. In a word, all this sounds too much like a sentimental and somewhat cheap novel about life in high society.

The orchestra of invalids began to play the waltz “Mignon” and the illusion of “high society” immediately disappeared. In conformity with the orchestra were the clothes, in conformity with the clothes were the dances. Cymbals, pipes, something resembling tambourines, an old whistle, and violins. Among the violinists were a gypsy and a Jew, the latter’s violin trying all the time to play something very sad instead of the well-known melodies, but when it fell into a merry vein it played something resembling “Seven on a Violin”. And dances that had long gone out of fashion: “Chaqu’un”, “pas-de-deux”, even the Byelorussian mannered parody on “Minuet” — “Lebedik”. And luckily I could dance all of these, for I liked national dances.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН