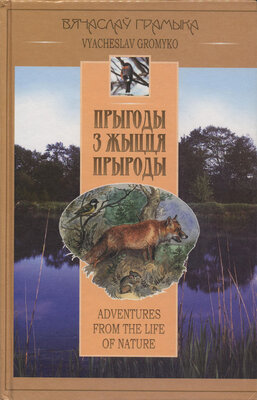

Прыгоды з жыцця прыроды

Adventures from the life of nature

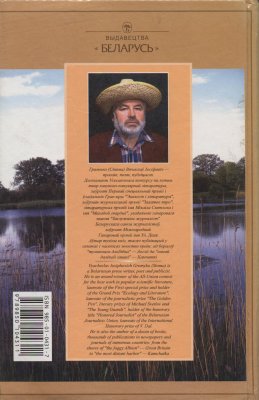

Вячаслаў Грамыка

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 263с.

Мінск 2003

The period when wolves provide their cubs with food is very dangerous for the animals, which are not predators, especially for the young ones. Poking about in the nearby area, wolves attack hares and piglets, broods of birds and pick eggs from the nests.

At the age of two months wolf cubs begin to accompany their parents to the hunting — at first they learn to eat pieces and gnaw black cocks, hares, ducks, which their parents bring, later on they begin to catch little animals themselves.

When autumn comes wolves again gather into packs and at first keep not far away from their lair, but with the first snow

they resume their wandering life. When snow becomes deep, wolves make long night marches. During these marches a pack is led by an old she-wolf and an old wolf brings up the rear.

Beside the damage, which wolves cause to cattle breeding and wild faunae, they, at the same time, play a positive role in nature, too. What kind of? First of all, wolves eat sick and weak animals. They don't hesitate to eat one of their own breed, and in this way only strong and healthy animals survive and give birth to strong and healthy wolf cubs; by eating carrion they, to a great extent, prevent spreading numerous dangerous diseases and epidemics. As we know, a wolf is the ancestor of domestic dogs. But a wolf is a wolf, whatever we say about it and for a farmer it is an enemy and the enemy, which is especially dangerous when the their number greatly increase in some area... Just with such cunning and dangerous beasts of prey had we to deal with at that time when living in a small village...

After the above-mentioned occasion, wolves reminded us about themselves from time to time. News came from one or another small village — in one village they cleaned a hen-house, caught a young dog in another, slaughtered a sheep in a shed somewhere else.

So farmers couldn't have a sound sleep anymore. Worries about their domestic animals didn't leave them. They listened intently to any barking of a dog looking anxiously into the night darkness through the window and from time to time they went into the shed to see if everything was alright.

Sometimes, a group of hunters started to search for wolves, but their search was never a success.

Father also tried to trace wolves but... in vain.

It happened so that just at that time a sick mare died and father had a talk with the veterinarian and the foreman and asked them to give him the mare for bait — and he got it. Not wasting time, the men brought the dead animal to the nearest forest and, without getting off the sledge, so as not to leave any footprints (wolves are very cautious about mans footprints), they put it in the snow. It should be mentioned that they have chosen a very suitable place, on the outskirts of the forest, far from the local road, near a straw stack, some 34 paces from it.

One could have a good view of the area around from there, and it was possible to make an ambush at the straw stack.

When they came back father went to the neighbor and asked to lend him a gun. He carefully sorted the cartridges and when it was getting dark he got into the same farmstead sledge, put on a very long, practically to his ankles, sheepskin coat and headed for the place where he expected to meet wolves. My elder brother took him there.

When they were passing the straw stack father jumped out of the sledge (so as not to leave any trace), hid in the stack and began to wait quietly. My brother hurried home.

On that day wolves didn't come up to the bait. Neither did they come the next day or in two days. It was evident that the beasts had felt the bait, but either they were extremely cautious or suspected something.

From time to time, one could hear their howl in one part of the forest, then in another. Father was a very brave man, otherwise he wouldn’t have dared to be in the ambush alone, but he said that when they had been howling nearby, his hair stood on end. He said that the wolves had been howling forcedly, but at the same time one could feel their wild strength, horror...

On the sixth night, father stayed at home. He didn't have any more illusions and, besides, he was very tired. In the morning he went to have a look at the bait and found... nothing there. Only a trampled-down ground remained at the place where he had put the bait. The wolves hadn't left even a bone.

Meanwhile, preparations for a big hunt were underway in the neighborhood. Farmers had not once asked the hunters to hunt wolves. It should be mentioned that the hunters had not once tried to hunt wolves, but without any success, and now the hunters themselves turned for help to the neighboring forestry to the old forester Andrey Kuzmich, whom the farmers called among themselves Kuzmich or Yokha-makha (as the expression “yokha-makha” was his favorite one and he used it whenever possible or even impossible). “So I went, yokha-makha... and so it did, yokha-makha... What a silence, yokha-makha!” you could hear the old forester say to his relatives, to his friends or strangers.

Kuzmich Yokha-makha lived almost all his life in the forest, probably he was born there, too, but nobody mentioned it. There was no one who knew the forest as well as he did. Kuzmich knew where this or that herb grew, what properties it Lad and so on. Kuzmich was fond of picking mushrooms and nuts, but he loved forest animals most of all. Since his childhood, he had learnt their habits, their behavior and this constant link with nature gave him kindness and modesty, but that inappropriate “yokhamakha” spoiled the whole impression of him a bit. Sometimes, it somehow reminded that he was a bit rude and unrestrained, and at times, on the contrary, that he was simple and honest, depending on the intonation he said it with (Note: “Yokhamakha” is a literary diminutive variant of the Russian swear expression “Goddammit! — KG”).

Kuzmich was always in touch with forest inhabitants. Sometimes a weakened roe deer lived in his shed, or it could be an injured hare or a bird with a broken wing. The forester gave some grain to the birds in winter and put hay and besoms of tree branches that he had made in summer for hoofed animals. He perfectly new or could foresee how this or that animal would behave in a certain situation or what this or that cry of a forest bird meant, etc.

By footprints of animals on the snow, Kuzmich could read episodes from the life of any forest inhabitant. No wonder that the old man was greatly impressed by the farmers' stories about the damage caused by wolves and he decided to organize a collective battue on wolves. For this purpose he at first wanted to find out, in detail, what was going on in the neighborhood and then to make up a plan as to what steps should be undertaken.

Kuzmich visited many houses in the village, travelling on his wide hunting skies. He made a round of a number of small villages, spoke with the farmers questioning them about the wolves, listened attentively to both the old and the young and little by little made up his plan. Later on he began to study and puzzle out the wolves' footprints comparing what he had heard and seen.

So once when he went out to the field, which was not far from the forest, Kuzmich noticed a chain of wolves' footprints and began to study them attentively.

It was early morning, but at night it had snowed heavily and the snow covered all the former footprints. The remaining footprints were, no doubt, fresh. Kuzmich noted that... Even when there was no snowfall he could easily tell fresh footprints from the old ones and in this case... It should be added that his well-trained eye could catch even the smallest details. His fingers felt the thickness and sharpness of the edges of any old footprints, he unmistakably determined, by the dampness of the paw imprint, in what weather the animal had passed this place — whether it was frosty or slushy, windy or not, whether it was sunny or the day was gray. So, Kuzmich could interpret any forest mystery.

He had no doubt that the footprints he had found were fresh ones. Though the snow, which had fallen at night, covered all the former animal paths, the old forester could see well the character of the imprint and it was not difficult to make out if it was a fresh imprint. When stepping into deep snow the wolf tramples it down putting the paw under a very sharp angle, and he pulls it out almost vertically. In the place where he lowers the paws, it always infringes the edge of the imprint a bit forward drawing with the paw on the surface of the snow in the direction of the movement. There remains a small furrow (drawing) on the snow and when a wolf pulls out the paw it squeezes the edge of the imprint; when he takes the paw off the snow, it leaves a drawing on the snow.

By the angle of the imprint, trampled down while drawing the paw, the direction of the wolves' movement was easily read. Fresh furrows on the imprint helped Kuzmich to determine that the wolves had passed by in the very early morning. The edges of the imprints were sharp and not covered with ice yet and this confirmed once again that the footsteps were fresh.

Then Kuzmich determined that there were 6 to 8 wolves in the pack and, as usual, it was led by an old she-wolf. An old wolf brought up the rear. It was easily seen by the last clear imprint of the wolf s paw, which is always greatly different from the she-wolfs

imprint, by its solidness and much more rounded shape. There was an almost quadrangular heel on the imprint, which is not characteristic of a she-wolf. By footprints Kuzmich could easily tell a she-wclf from a wolf, though for him as for any hunter no matter how experienced he was, it was much more difficult to make out whether it was a she-wolf or young wolves, one or two years old.

Kuzmich knew well that a file usually consisted of old wolves — a she-wolf and an old wolf; very young first year wolves and grown-up wolves which haven't made their own families yet, last year wolves and the youngest, wolves of this year — restocking ones. But having looked thoroughly at the footsteps the old forester decided that there were no such wolves of this year, there was no disturbance in the character of footprints. He noticed the footprints of some first year animals. He understood that the she-wolf leading the pack was not primiparous. That didn't correspond to the size of her footprints in any way. He also knew that the previous brood had been lost. Such a pack is most dangerous, as it is embittered and bloodthirsty.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН