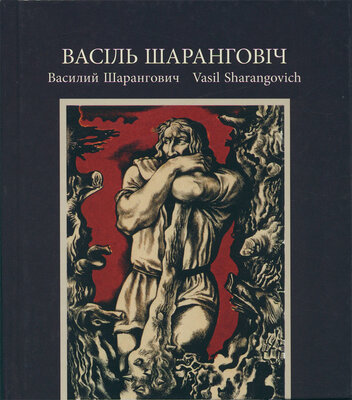

Васіль Шаранговіч

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 74с.

Мінск 2024

But let’s go back to “The Narach Land”. I broke the contract. I practically abandoned linocuts, switching to lithography instead. Nevertheless, I kept the original prints. While preparing my 60th birthday exhibition, I suddenly came across those illfated engravings. I carefully examined them and came to the conclusion that actually they’re not that bad, and there will be no shame in including them in the exhibition. And that was it! My colleagues were also very positive about them”.

In 1967, Vasil Sharangovich received an offer to become a teacher at the Belarusian State Theatre and Art Institute, and then in 1972 — to become head of the

31

graphic art department. Already in 1986, he became vicerector, and in 1989 — rector of the Institute, which during his tenure was renamed the Belarusian Academy of Arts. Over his 30 years of tireless work, he raised a constellation of talented students and basically created the Belarusian school of graphics, raising the prestige of graphics to unprecedented heights. The competition for this department was enormous — young artists were eager to study under Sharangovich, one of the greatest masters of the era.

In 1978, Vasil Sharangovich was awarded the title of Honoured Artist of Belarus, being the youngest artist to receive it at that time. In 1981, at the age of 42, the artist received the academic title of Professor. In 1991, Sharangovich was awarded the title of People’s Artist of Belarus. In 1995, he became an academician of the International Academy of Sciences of Eurasia. From 1997 to 2008, the artist headed the recently established Museum of Contemporary Fine Arts in Minsk.

The 1970s and 1980s were very fruitful for Vasil Sharangovich; he spent them under the sign of the poetry of Yanka Kupala. In 1976, the Mastatskaya Litaratura publishing house commissioned the artist to create illustrations for a collection of works by the great Belarusian poet (“The Eternal Song” was to be published as a separate edition). Sharangovich agreed with great joy.

Vasil Sharangovich completed 22 colour lithographs. He wanted to create not just illustrations, but symbolic works of monumental nature, which was most consistent with the polysemantic poetry of Kupala. The poem “The Eternal Song”, although short, reflected the entire life of a peasant, from birth to death. It gave the artist enormous opportunities for interpretation, since the poem organically combined a realistic display of life, allegory and almost surreal elements.

Kupala’s poetry did not let Vasil Sharangovich go; for a long time he was fascinated by the poet’s wellknown piece “And, Say, Who Goes There?” The lithograph made by the artist for this poem is monumental, consisting of three parts. In the centre is Yanka Kupala himself against the backdrop of his comrades — famous Belarusians, representatives of different historical eras, and ordinary workers. On the left are the poor, with their hands outstretched, and on the right are the same people in search of a better life, and this is the main thing the famous poet dreamed of.

32

The triptych “Where the Eternal Grudge Ripened” seems to draw a line under Sharangovich’s interpretations of the poetry of Kupala. This work is the result of the artists many years of reflection on the poet’s work, on human life with its joys and hardships. The inner beauty of motherhood, the power and strength of the unconquered “master of the plough and the scythe”, the profound idea of earth as our nurturer — this is the leitmotif of the entire triptych.

For the Belarus publishing house Vasil Sharangovich also illustrated “Confessions of a Heart”, a book by the Belarusian poet Anton Bialevich. This was a journalistic work, a kind of a fusion of the authors own thoughts with visitors’ impressions of the Khatyn Memorial; included in it were Bialevich’s poems and reflections as well as eyewitness accounts of those events. Working on the book forced the artist to reflect on his own wartime memories. He developed a new technique — a combination of red gouache and black ink, which was very consistent with the content of the book. The flaming red colour is like the burning earth, blood on the bodies and souls of people, and black is a symbol of what remains after the fires.

Working on Anton Bialevich’s book prompted the artist to create an easel series on this topic. The name of the series “In Memory of Fiery Villages” came to him immediately after reading the book “I Am from the Fiery Village” by Ales Adamovich, Yanka Bryl and Uladzimir Kalesnik, which shocked him with its harsh documental quality and at the same time the nightmarish unreality of the events. As a child, he had to see only the results, the traces of the occupation, and in the book the actual witnesses were given a voice.

The work lasted six years. The artist eschewed realism while building the compositions of some of the works, shifting visual planes, adding an almost surrealist touch. In fact, when reading eyewitness accounts of those events, one finds it difficult to imagine them as real. Inhuman loss and pain, blank hopelessness and desire for life, death and struggle... One of the sheets is dedicated to the artist’s father (“Partisan Blacksmith”), and the final one to his mother (“The Return”).

For the series “In Memory of Fiery Villages” Vasil Sharangovich received the State Prize of Belarus in 1986.

33

The illustrations for two important poems of Belarusian literature — “Pan Tadeusz” by Adam Mickiewicz (1985; 1998) and “New Land” by Yakub Kolas (2002; 2014) — were also significant parts of Sharangovich’s body of work.

In this poem, now considered a classic work of romanticist literature, Adam Mickiewicz developed a comprehensive picture of the life of the Belarusian gentry, created an entire gallery of distinctive images, and glorified Belarusian nature with great love. For this set of illustrations, Vasil Sharangovich read mountains of historical literature, carefully studying the costumes of that era, household items, weapons, etc. The artist sought to show the poem’s characters in closeup, outlining the scene with only a few details. The cycle consisted of 24 illustrations and 12 chapter headings. The illustrations were made with watercolour, as it suggested a more emotional interpretation of the poem’s contents.

But “New Land” by Yakub Kolas set new tasks for the artist.

Vasil Sharangovich remembered well the peasant way of life our poets wrote about, and felt nostalgic for his youth. That’s why for many years he wanted to return to “New Land”, the book of his childhood.

Yakub Kolas deeply loved the “Godforgotten land” of his fathers; he sang a majestic hymn to the beauty of Belarusian nature and a bitter song to the gloomy stagnation of the dispossessed. “New Land” presents an almost complete calendarlike cycle of rural life — spring, summer, autumn, winter — which includes the joys and hardships of the peasant, the quiet family and church holidays, and the fascinating world of childhood. The leitmotif of the poem, “to buy land, to acquire a corner of one’s own, to get out of the shackles” — is Michal’s vivid dream, which remained only a dream.

“New Land” consists of thirty to a certain extent independent sections. Since the publication was planned in three languages, it was necessary to complete 90 illustrations, a frontispiece and the cover design.

The artist created his illustrations for “Pan Tadeusz” according to all the rules of classical art: he started with sketches, then detailed drawings, which were transferred to blank paper, and then completed the original illustrations. With this work, Sharangovich only made smallscale sketches and then painted on Whatman paper right away. Watercolour requires clarity and does not tolerate

34

major edits, but there were so many figures, faces, hands and eyes! The images were created on the fly; the work proceeded spontaneously, but in full accordance with the much earlier original idea.

Vasil Sharangovich said: “...there is still no peace in my soul, since it seems that not everything has been done yet, and I still live in the New Land. It is eternal, just as life itself is eternal, despite our short earthly journey; and art, in general, is eternal, if it is truly art. I am grateful to fate that it connected me with such geniuses of the Belarusian land as Yanka Kupala and Yakub Kolas. The poetry of these titans, the feats of their life have always amazed me, given me strength, and inspired me to do something of importance in my life and work, so that I could have the right to say in the words of Yanka Kupala: “I repaid the people with whatever was in my power...”

Vasil Sharangovich devoted the last years of his life to watercolour landscapes, mainly those of Myadzel, their distinct originality transformed by his perception: the complete fusion of man and nature, their eternal harmony. The refined plasticity of watercolours helped the artist create unique, universal, timeless images of nature.

The artist also began to paint a series of portraits of Belarusian cultural figures, but didn’t manage to finish it. One of the best is the portrait of Stefania Stanyuta.

On December 31, 2021, two days after the death of his wife Galina, with whom he walked hand in hand for 56 years, Vasil Sharangovich passed away. The star of life has faded, but the star of creativity shines on to this day.

Natallia Sharangovich

Партрэт Францыска Скарыны. 1971

Портрет Францнска Скормны. 1971

Portrait of Francysk Skaryna. 1971

37

Янка Купала. «Яна і я». Ілюстрацыі. 1978

Янка Купала. «Она н я». Нллюстрацнн. 1978

Yanka Kupala. “She and I”. Illustrations. 1978

38

AXTO TAM Ідзе, A ХТО TAM ІДЭДУАІТОМІГ

АЧАГО ЗАХАЦВААСА ІМ, ПАтРДЖАНЫМ МК,Ь

тлкой грлмвдзе?Беллруш

А хто там ідзе?

Па матывах верша

Янкі Купалы.

1976

А кто там ндет?

По мотмвам

стмхотворення

Янкм Купалы.

1976

And, Say, Who Goes There? Based on the poem of Yanka Kupala.

1976

41

Партрэт Янкі Купалы. 3 серыі па матывах паэм Янкі Купалы. Дыпломная работа. 1966

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН