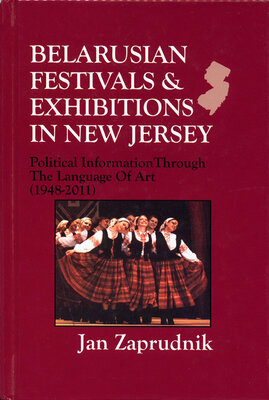

Беларускія фэстывалі й выстаўкі ў Нью Джэрзі

Янка Запруднік

Выдавец: Беларускі Інстытут Навукі й Мастацтва

Памер: 219с.

Нью Йорк 2013

Meanwhile two ladies are passing by. One on them just glanced at me, but the other stopped and attentively concentrated her sight on my dress and the rest of my surroundings, while 1 remained silent and immobile.

"Why did you stop?" I hear the voice of the front lady, who slowly approaches me. And the curious one says in half-voice: "Do you think it's a dummy?"

I could not resist a smile. Both of them, jumped while laughing loudly and, somewhat embarrassed, began apologizing. I laughed along with them.

After a short conversation about my country of origin and spinning technique we parted as friends.

"I bet you 're hot as hell"

At the festivals in Liberty State Park there were always press correspondents and TV reporters. Once on a hot day a journalist approached me and, while I kept spinning, examined in detail my dress, in which I was covered from head to toe, with just my face and hands visible. After a short while he says: "I bet you're hot as hell." And I replied: "Not exactly, because my blouse and head dress are from flax, not synthetic. The linen is much less heat-preserving than synthetics." He touched the sleeve of my blouse feeling it by his fingers and did not second his bet.

Nadja spinning.

"Do you speak English ? "

My Palessie dress — mostly, I think, the head dress, namitka, covering my head and neck, as well as bast-woven shoes (laptsi) that my brother Mikhal Rahalewicz had made for me — looked to many a visitor like an exotic overseas wear, especially at a festival near the Statue of Liberty, where ships full of immigrants were moored years ago.

During a festival two TV reporters were passing by my spinning exhibit. One of them, after staring for a while at me, says to the other: "Have you ever seen anything like this?!" And the other, smiling, shakes his head negatively. And then bending over me asks: "Do you speak English?" "Of course I do," I said. "I have been in this country for over thirty years."

And then he started interviewing me about my spinning flax tow, my costume and the country of origin. A small part of that interview was shown later on TV.

"What do you do with these hairs?”

Festivals were visited often by school children. When I spun flax tow, some viewers admired the agility of my fingers. Sometimes they wanted to know how long my thread would be after an hour of spinning.

At the outset of our festivals, the tow was sent to me from the Bielastok region.29 Later, my niece Tamara Rahalewicz found a source in Pennsylvania. When I spun at festivals, some school kids asked me: "What do you do with

these hairs?" I explained to them that these are not hairs but flax tow. I kept at my side a little sheaf of flax and, in a basket, half processed flax stalks. 1 explained to the students that the tow is made of processed flax stalks, and that from flax seeds oil is pressed out. 1 would give them small bags of seeds and advised them to pot the seeds to see the plant. I also included a brochure with information about Belarus.

"Sell me this spinner"

The staff I used to demonstrate spinning was made for me by Aleh Machniuk, a talented member of our South River community. The spinner was authentic: it was a replica of one given to me by

61

Nr

Mrs. Nadzia Zacharkiewicz, mother-in-law of my nephew Siarhiej Rahalewicz. She took it along when she was leaving her native Palessie in 1944. She gave it to me as a gift, and it served me not only as a tool but also as a reminder of my homeland.

One day at a festival in Liberty State Park, a Ukrainian woman came to me as I was spinning. She stood for a while and then said in Ukrainian: "I also have a staff, but no spinner. Sell me your spinner." I told her that I need the spinner myself for my demonstrations. That's the only one 1 have. But she did not seem to hear me. "Sell me your spinner," she insisted. 1 repeated my answer. She departed. And then came back again with her "sell-me-your-spinner" request. Unfortunately, I could not accept her business proposition. She did not make a fourth request.

Somewhat later, two spare spinners were made for me by my countryman, Ivan Alkhouski, but I never again saw my potential Ukrainian buyer.

Men learning the ropes.

Bast Shoes

The first pair of bast shoes were woven for me by my brother Mikhal. One day I said to him: "Mikhal, weave a pair of bast shoes for me." "Bast shoes?! What do you need them for?" I answered: "First weave, then 1'11 tell you." He did it. He lived

in Pennsylvania, a distance away from my home in Somerset, New Jersey. Only when he had woven bast shoes did he team about our festivals in Liberty State Park. I must say that on hot summer days, when you have to sit all day with the staff and spin, wearing bast shoes is much more pleasant than having your feet in tightly laced high leather shoes.

Later on, for demonstrations of national costumes as well as for the Vasilok dancers, bast shoes were made by Valodzia Rusak. He even taught some young dancers to weave them. Thus, the costumes on the models and dancers were authentic from head to toe.

. A < 62 St

A Protest by Lithuanians Concerning the State Emblem

Once we joined a group of Belarusians in Pennsylvania who participated in a multiethnic display of folk arts. Our participation was organized by Halina Kuczura, a Pennsylvania resident. Upon arrival, we laid out our items: dolls, straw-inlaid boxes, spreads, etc., along with information leaflets. We also hung, on a movable wall a map of Belarus and the Pursuit, our national coat of arms.

In no time, we were approached by local Lithuanians who, indignantly, asked us: "By what right do you dare to hang up our coat of

Belarusian

exhibition in Pennsylvania. From left: Nadja Kudasow, Irene Dutko and Halina Kuczura.

arms?!!!" We explained to them that this is the coat of arms of the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which included Belarus, and of the Belarusian National Republic, proclaimed in 1918. But our words were no argument for the objectors. They insisted that we remove the Pursuit from our stand. When we told them that this will not happen, they rushed to higher authorities of the exhibition center to press for their demand. But the administration told them it cannot take sides in such a contention, and this was the end of the dispute. Both stands, Belarusian and Lithuanian, remained decorated by the Pursuit,30 one horse with the tail pointed downward and the other one with the tail pointed upward.

Nata Gernat (Rusak), a Vasilok dancing group member, recalls challenges she and her friends encountered in their performances.

>4 63

Common and Less than Common Dancing Challenges

Most dancers, over the years experienced expected and unexpected problems, and had learned to deal with them. The directive was to keep dancing no matter what. This resulted in dancers having to throw off shoes and uncooperative headpieces. The unavailability of a dancer for a performance would oblige the group to reconfigure the dances to accommodate the smaller number of dancers.

Feet were occasionally stepped on; stages shook and separated (once at Liberty State Park), requiring dancers to constantly adapt. One particularly challenging moment occurred when dancer Lyda Daniluk broke her toe during a Garden State Arts Center performance, and managed to complete the dance, with the support of fellow dancers. Injuries of varying degrees were part of the territory.

Slippery Floors Make for Interesting Dancing

In preparation for the festivals, many practices were held by the dance groups, culminating in dress rehearsals held in front of Nick Jordanoff, and program coordinators Halina Rusak and Irene Rahalewicz-Dutko. These dress rehearsals were held at the South River Belarusian-American Center. The floors in the nicely finished hall were caringly cleaned and polished. During one number, the female dancers were required to join hands in a circle, and leaning back, dance quickly in one direction for several turns. As the dancers circled it became more difficult to hang on to one another. Under ordinary circumstances, a lost grip would quickly and unnoticeably be reestablished. Unfortunately, the addition of the clean, glossy floor to the equation sent dancers flying, or rather sliding across the floor (a Belarusian form of break dancing?).

Luda Grant (Rusak), a Vasilok dancer, adds two colorful episodes to the list of events.

Stuck at the Dump

Even the heat wasn't daunting for the enthusiastic dancers and hosts. The journey from New Jersey to the Brooklyn, New York, practice hall had been made without a hitch for decades. This would be the last rehearsal before the Garden State Arts Center performance the next morning. A few weary Canadian performers attended. Dances were perfected and a few extra prysiadki (squat kicks) were inserted for punctuation. Practice was over. We were bound for New Jersey for some late night fortification (midnight pizza) with our Canadian friend driving the car. Luda and Alice knew the route well. Unfortunately,

-s

С 64 >

the car was more tired than the dancers. We were forced to stop and evaluate the car trouble. Near the Staten Island dump... for hours! We politely imposed on strangers, very late at night (or early in the morning), for the use of their phone. We were too anxious to sleep in the car. We waited. Help arrived and we finally lumbered home.

Rooms Packed with Overnight Guests

Nick Jordanoff, a frequent guest at this point, was also spending the night at the Rusak house. Every sleeping person was involved in the festival in a few short hours. It never seemed to matter how many beds were needed for visiting friends. The walls of the house always stretched in order to accommodate our favorite people! Several dancers crept into their rooms. My mother, rarely tired herself, promised not to awaken us until the last possible moment so that we could soak up some energy to propel us for the next two days of dancing! We only slept for a couple of hours. We were grateful to know that at some point our adrenaline would help us. My parents31 fed us breakfast and sent us on our way. They were always happy and proud to be part of this artistic process. They enjoyed having a house full of laughing visitors! We all forgot how tired we should have been and enjoyed a fantastic life experience promoting Belarusian art. We also collected another story of great times with Belarusian friends.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН