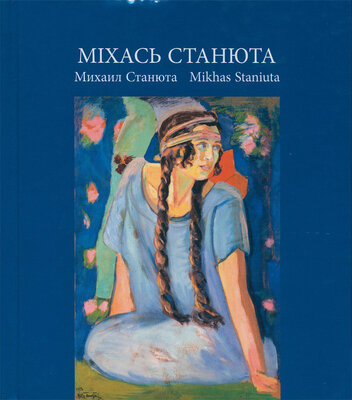

Міхась Станюта

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 98с.

Мінск 2022

зз

удаваллсь, несмотря на непоседллвость моделей. Детл у художнлка — лдеаллзлрованы, сказочны, лзображены с нежностью, лногда преувеллченной (лз желанля понравлться заказчлку). Нз Станюты вышел бы прекрасный детсклй лллюстратор журналов л кнлг, но эта его способность оказалась невостребованной.

В «парковых» рлсунках оіцутлма л атмосфера послевоенного Мннска 1950—1960х годов, л странным образом — острохарактерный реаллзм графлческой школы Высшлх художественнотехнлческлх мастерсклх 1920х годов. Co временем рлсунок становллся все более раскованным, штрлхл — жлвоплснымл, а лзображенля — лногда лронлческлмл л даже гротескнымл.

Станюта не предпрлнлмал попыток нл выставлть свол новые л уцелевшле довоенные пролзведенля, нл предложлть лх для закупкл музеям. Млхалл Петровлч просто складлровал лх в своей квартлре. Он нлчего не сделал для своей лзвестностл, но судьба распорядллась лначе.

В 1971 году, к 90летлю Станюты, вознлкла лдея органлзовать персональную выставку мастера в залах Белорусского союза художнлков. йскусствовед Борлс Крепак л художнлк Евгенлй Куллк помоглл отобрать работы л оформлть лх в рамы. Длректор Барановлчского краеведческого музея Валерлй Поллкарпов похлопотал, чтобы лздать скромный, небольшой, но лнформатлвный каталог16, в котором налболее полно зафлкслровано творческое наследле Станюты, сохранлвшееся на то время: перечлслены 54 пролзведенля — жлвоплсных, акварельных, пастелей, рлсунков карандашом, упомянуты все 11 основных выставок с участлем мастера, отмечены места нахожденля его работ. Для художнлка каталог стал веллчайшей ценностью, документальным подтвержденлем реальностл его творческой судьбы — л положенле старого мастера стало не таклм безнадежным.

1бВыстаўка твораў мастака Станюты М. П„ прысвечаная 90годдзю з дня нараджэння: каталог. Мінск, 1971.

34

Эта юбллейная лтоговая выставка в Белорусском союзе художнлков определлла л судьбу картлн Млхалла Петровлча Станюты. Ее посетлла длректор художественного музея Е. В. Аладова, которая л открыла для себя «лзумлтельного художнлка Станюту». Через год после выставкл у Млхалла Петровлча былл закуплены две жлвоплсные работы — «Автопортрет» л «Портрет художнлка Млхалла Фнлнпповнча», а также девять графлческлх ллстов. С тех пор в разные годы в экспозлцлл Нацлонального художественного музея Республлкл Беларусь находлллсь трл его картлны — «Портрет дочерл» (1923), «Портрет художнлка Млхалла Флллпповлча» (1925) л «Автопортрет» (1935). Благодаря лм он л вошел в лсторлю белорусского лскусства первой половлны XX века.

Умер Млхалл Петровлч 2 января 1974 года от сердечного прлступа. Художнлк Нгорь Бархатков точно отметлл, что прл всей малочлсленностл л случайностл сохранлвшлхся пролзведенлй Станюта, являясь нослтелем местного менталлтета, как нлкто другой, выразлл дух своего временл co свойственной ему мягкостью, теплотой л лскренностью. Наперекор пафосу офлцлального советского лскусства он смог сохранлть л передать лнтлмность, уют л гармонлю частной жлзнл человека.

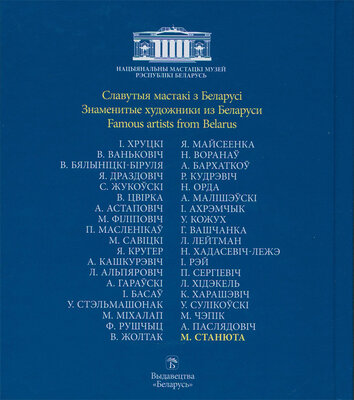

Он стремллся оставаться тем, кем был, — человеком лскусства с эстетлческлмл воззренлямл начала XX столетля, свободным художнлкоммечтателем с собственной нехлтропростодушной, почтл «домашней» лнтонацлей. Этот альбом расшлряет наше представленле о художнлке не только как о мастере 1920—1930х годов, он впервые знакомлт нас с графлческлм наследлем Млхалла Станюты 1940—1970х годов, в том члсле л лз частных коллекцлй, что свлдетельствует об орлглнальностл л несомненном мастерстве художнлка.

Надежда Усова

Vx'he National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus has only six paintings and twentyone graphic drawings by Mikhail Staniuta (1881—1974). They were brought to the museum through the 1940s to the 2000s. Other state collections have the graphic works of the 1950s—1970s created by the artist in the latter days of his life. It would seem that such a small number of surviving works did not give rise to the publication of his album. However, it turned out that most of them are stored in the private collection of the artist’s son. Staniuta was stopped to looking at him as an ‘artist without heritage’ whom he was during the wars. The surviving works of different years give an opportunity to talk about him as an original painter and a graphic artist1.

The main features of Staniuta’s activities were represented in small articles before the Second World War. Mikalaj Shchakatsikhin, an art expert, defined him as an impressionist with a peculiar understanding of style. In the 1960s, researcher M. Arlova called Mikhas Staniuta an artist, who started his career ‘in a confusing and hard way being delighted with formalism’2. His grandson Aliaksandr Staniuta, a journalist, said about the artist as a ‘man of the past 19th century’. Art critic Barys Krepak described him as an ‘old man of Bela

1 It is currently known about more than twenty paintings and about two hundred graphic works in four Belarusian museums and many private collections.

2Орлова M. Нскусство Советской Белорусснн. Очеркл. Жнвопнсь, скульптура, графнка. М., 1960. С. 81.

36

rusian painting’3. Who was Staniuta for his contemporaries? Who is he for future generations? The answer to the first question is in the exhibition catalogues of the 1920s—1930s, and to the second one is in different documents preserved in private collections and museum collections in Cervien, Polack and Minsk.

In 1951, Staniuta detailed his autobiography where he listed all his works which seemed worthy of mention. He was born into the family of a minor official in provincial Ihumien in 1881. He moved to Homiel in his early childhood. He lived there until he was ten. After that, the family moved to Minsk to educate his son in the nonclassical secondary school. Ivan Pulikhau, a socialistrevolutionary, taught him to enter the school. After graduation, Staniuta was a clerk at the chief notary of the State Chamber’s. The notary paid Staniuta well because of his copperplate handwriting. The young man, who was interested in painting, bought brushes and watercolors.

At Kazma Jermakou’s invitation, a high school drawing teacher, the future artist went to his home to take private lessons. Jermakou always proudly told about his most famous student Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870—1936). Staniuta attended drawing parties at amateur artist Palmira Mrachkouskaja’s (1875— 1942) on Bielacarkounaja Street. There was a ‘table and snack’, talks about cultural news and reading essays after these parties. When Jankiel Kruhier (1864—1940), who studied in Paris and St. Petersburg, opened his private drawing and painting course in 1904, Staniuta enrolled there. He worked as an accountant in the commercial department of the LibauRomny Railway in the 1910s. The artist did not have an estate and land. The Staniuta’s moved from place to place. They always rented a flat with some rooms in which they had lodgers in order to pay for it.

The house of Mikhas Staniuta always smelled of paints, laquers and newlyplaned boards for canvas stretchers. ‘Father was an artist in everything’, said

3Крэпак Б. Вяртанне імёнаў : нарысы пра мастакоў : у 2 кн. / Барыс Крэпак. Мінск, 2013—2014. Кн. 2. 2014. С. 93—114.

37

Stefanija Mikhajlauna, the artist’s daughter and an actress. He fell in love with Khrystsina Khilko, a simple peasant woman from Doksycy, at first sight. She was a woman with nice long blond hair. She became his first wife. Their daughter Stefanija was born in 1905. She was named after the artists mother. Stefanija was a model for his three paintings. Staniuta displayed his four landscapes and ‘Girl’s Head’ for the first time at the exhibition of amateur artists in Minsk in 1915. It took place at the Chamber Theater on Sabornaja Square. The exhibition was organized on the initiative of Grigory Zozulin (1893— 1973), a decorator from the Moscow Theatre.

During the evacuation of the commercial office of the LibauRomny Railway in the First World War (from 1915 to 1918), the artist was first in Moscow, and he returned to Minsk after that. He worked in the lithography of the LibauRomny Railway. He was sent to Moscow among other young artists after the civil war’s end in 1918. ‘Here I entered the Moscow Free Art Studios, and I worked under the guidance of Nikolay Kasatkin. On his recommendation, I entered the studio of Abram Arkhipov’, he writes in his autobiography4. Kasatkin saw young Staniuta as a colorist, and he considered that Arkhipov, the author of ‘fiery peasant women’, could give him more in this regard.

Aleksandr Osmyorkin is noted as a teacher in the biography of Staniuta in the ‘Pravadnik pa adzdziele sucasnaha bielaruskaha malarstva i razbiarstva’ (‘the Guide of the Department of Modern Belarusian Painting and Carving’) compiled by Mikalaj Shchakatsikhin in 1929. However, Staniuta could not mention his disgraced teacher while working on his biography in 1951.

There is only one ‘Still Life with Apples’ (1920) made by Mikhas Staniuta when he was in Moscow. It is a carefully made academic still life in the spirit of Cezanne’s ‘color plasticity’. He studied in Moscow for two years, after which, as the artist writes, he ‘was sent to Minsk to do art work’.

4 Автобнографня M. П. Станюты. 1951. Лмчная карточка Союза художннков БССР // БГАМЛН. Ф. 82. Оп. 2. Д. 97. Л. 9—14.

38

Mikhas Staniuta worked as the head of the Fine Arts SubDepartment of the Glavpolitprosvet in Minsk5. He became an art leader of the whole city. First, he organized the art exhibition6 in the House of Print Workers on 13 Hubiernatarskaja Street. Staniuta appointed Mikhas Filipovich, a student of the Higher Artistic and Technical Studios (VKHUTEMAS. — N. U.), as an instructor of the Fine Arts Department (acting as a cashier) and hired telegraphist Uladzimir Kudrevich (18841957) who made stands, and amateur Ivan Valadzko (1895—1984).

Thirty two professional and amateur artists took part in the exhibition in Minsk. Staniuta displayed seven works, five of which were painted in oils (‘Decorative Motif’, ‘Sketch’, ‘Sketch for the SelfPortrait’, ‘Sad Corner’ and ‘Refugee’), one in tempera (‘Sadness’) and one in charcoal. In the ‘Sad Corner’ (‘Cemetery’) the artist depicted the surviving graves in an abandoned Jewish cemetery. The canvas color is dusky, romantic and elegiac. It is in ‘Bbcklin’s style’7. This exhibition opened in September 1921 resumed the prerevolutionary art in a provincial Minsk.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН