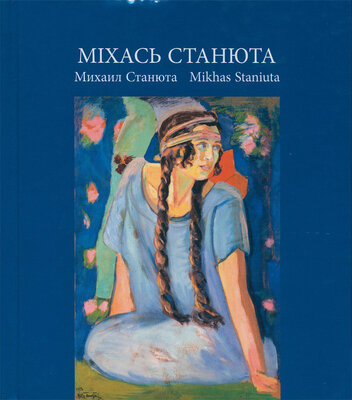

Міхась Станюта

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 98с.

Мінск 2022

43

set under the influence of changes in the political situation and the aesthetic climate, and chose the path of an ‘invisible artist. However, there was another reason for teaching.

' ! After the death of his wife in 1934, Mikhas Piatrovich met in the park with 30yearold Klaudzija Mazaliova, the daughter of a handicraft cooper from Mahiliou. She became his wife. She worked as a nanny. After that, she got a job in the factory kitchen. Staniuta made a gentle lyrical portrait of his young wife in pastel. Later, he painted her naked in the pose with her legs tucked under as he painted his daughter in 1923. He was in love and tenderness for the young woman in the flower of her beauty. The artist admires her femininity, delicate profile, sloping shoulders and smooth movements, although her body is not at all perfect. She was painted with her neck adroop against the rug. This is perhaps the only surviving nude portrait of the 1930s in Belarus.

The artist made his ‘SelfPortrait’ (1935) on the border between periods of creative activity. The artist appears as a youthful dandy in a coat and a tie, in a hat, worn smartly on the side of his head. The artist has his trim mustache and goatee beard, but his eyes are tense and confused. The hat at that time was an attribute of an intelligent and even successful person.

The artist made the portrait of student Niura, a friend of his wife, that time. This is a different, no less attractive type of girl of the 1930s, studying at the courses of a typist, a stenographer or an accountant. She is painted full face in a fashionable beret and coat. Staniuta painted in an easy manner. This is the beginning of a new period in the artist’s life. He stopped to be public, and he began to work creatively, independently, for himself, without regard for criticism from his fellow artists. The models of his works were members of his family and close friends. His motives are bunches of flowers and stilllifes.

Staniuta’s last known prewar work is his unfinished painting (1940) depicting the scene of a nocturnal confession by the fountain from Lope de Vega’s performance ‘Stupid for Others, Clever for Herself’ (Duenna). It was staged at the First State Drama Theater, where the role of Diana played by

44

Stefanij a. The painting disappeared during the occupation. However, it was miracously found by the artist in the vestibule of the city bathhouse in the Trinity Suburb. Today, it adorns the exposition ‘Room of Staniuta in the Museum of Theater and Musical Culture of the Republic of Belarus.

During the war, the elderly artist and his family except for Stefanij a (she was on tour in Odessa during the early part of the war) remained in Nazioccupied Minsk. They had hard life, and they had to sell things. Staniuta, as he said in his autobiography, painted landscapes and kerchiefs at home. He sold them at the market. He painted portraits in the streets, and he made copies of classical works for food. The artist made the portrait of his threeyearold son Uladzimir in pencil in 1942. The portraits of children during the occupation are a document of the time, as evidenced by the burnt sheet.

The master made pencil sketches of the Soviet soldiers in the streets, and he painted the landscapes of destroyed Minsk three days after the liberation of Minsk.

Staniuta did not return to active life as a professional artist even after the war. He became a member of the Union of Artists of the BSSR in 1945. There were no opportunities and conditions for working on painting in the 1950s. The family lived on Revalucyjnaja Street in a dark room with a potbelly stove. Staniuta mentioned that the living conditions were very poor, and ‘if I manage to get plywood, I will save 10 m2 for a studio’.

‘There were still forces, there was also skill, but, probably, he did not want to remind himself too much, because he did not fight, he was not a partisan, and he lived in occupation...,’ says son Uladzimir. Mikhas Staniuta remained a teacher and ‘an old man of Belarusian painting’. His close friends Jankiel Kruhier, Palmira Mrachkouskaja, Mikhas Filipovich, Uladzimir Kudrevich and Mikalaj Rusietski either died in the prewar or early postwar years, or they moved to Moscow or Leningrad. Frontline artists and artists of the new generation, who graduated from Leningrad and Moscow universities, came out on top. They painted a lot on war subjects. Staniuta understood that his time had gone forever. The Soviet man’s thinking had changed.

45

The artist’s paintings of those years are rare, so the ‘Portrait of Stefanija Staniuta, the Daughter and an Actress’ (1946) is something special. A shortcurled daughter in a dress made from American humanitarian aid, looking in a purse mirror, tinting her lips with bright lipstick. The moment, when the actress puts on makeup before the performance, is complemented by flowers (from numerous fans). Peonies stand in a bucket and mask the legs, the image of which was often not possible for the artist. This portrait is unique for the Belarusian Soviet art, in which the ‘dressing woman’ motif, so organic for the art of the first years of the 20th century, was practically tabooed as ‘bourgeois’. Woman had to be painted differently in the Soviet painting, especially in the postwar years: either as a worker, a production worker and a Stakhanovite, or as a mother, a sentimental and virginal girl, a devoted sister and wife. The exception was an artistic portrait, which allowed ‘artificial beauty’ — makeup and cosmetics. The father is proud of his daughter who is an attractive woman and a nice actress. The portrait evokes the joy of life and enjoyment of the first peaceful spring.

Staniuta taught drawing in schools until the age of 70. He took part in the exhibition only once in the Maiari House of Creativity of the USSR Art Fund in Riga in 1956. Dzintari, the former aristocratic part of the Riga seaside, built up with wonderful mansions of the early 20th century, was not damaged during the war. From there, the artist brought several sketches for his painting project, but unrealized ‘Fishermen on the Seashore’ (‘Riga Seashore’, ‘Dzintari’, ‘Boats on the Seashore’, ‘Foggy Morning. Dzintari’, etc.).

The artist’s romantic seascape ‘Dzintari. Sunset’ (1956) is a passe12 work of an unusual horizontal format showing an orange sunset, permeated with light sadness, the symbolism of color, transforming the real landscape of the Soviet resort into a dream landscape. Based upon the number of sketches, the artist

12 Passeism (from French passe past) is a shorthand of the art movement in the early 20th century. It referes to the past and its idealization.

46

worked on the landscape for a long time, trying to depict the haze and humid sea air on canvas.

Staniuta worked as a graphic artist after the age of 75. It is worth highlighting his series of 18 selfportraits in pencil and pastel, which surprises with the firstclass technical level of drawing, which he did not lose with age. The first pictorial ‘Sketch for the SelfPortrait’ (not preserved) was displayed at the exhibition in 1921. In the postwar years, the artist showed himself to be an old man who rethinks life at the end of a long journey. It is possible to compare his portrait with the Rembrandt series. The artist’s attribute, as in Rembrandt, is often a beret.

In a number of selfportraits made almost every two years, Staniuta depicts in detail the gradual signs of aging, realistically conveys his delicate psychological state. Some of the drawings are precise and descriptive, others are laconic, anxious and tragic. Several works present the artist as a mighty old man similar to Taras Bulba. Staniuta is a master of graphic psychological portraiture due to the personal series of selfportraits.

The artist made the socalled ‘park’ drawings made in the Chelyuskinites Park in the 1960s. It was made as a forest park in 1932 on the site of the former Vankovichy Forest, which was well known to the artist since the 1910s. There were family picnics in that area. The sky was never visible from the windows of his apartment in a new house on Kamsamolskaja Street opposite the Dzerzhinsky Club. It was difficult to work there. There were some stops to get the outskirts of Minsk, and the artist appeared in the pine forest within the town. Mikhas Staniuta sat on a bench next to the wooden Raduga Cinema every day. He drew the park and passersby. This was actually his studio. He needed communication and work on nature. He brought joy to people, which was sometimes regarded as an old man’s eccentricity, but it was a manifestation of higher wisdom. People surrounded him and watched how he made portraits.

These hundreds of drawings in colored pencils and watercolor were often created at a time. They are full of sincerity and warmth for people. This is a

47

kaleidoscope of different people, for example, professors and icecream sellers, children and bearded elders. The artist signed his name, surname and address. He also wrote creation time. There are often several dates on a sheet, which means that the artist agreed with his model for several sittings. They are residents of Minsk and visitors who were attracted by the park with its attractions and the Children’s Railway opened in 1955. People went to the park with its entertainments as chess, swings and a dance floor. Old people and children were in the park in the afternoon, but young people came there in the evening. So, the artist had many successful children’s portraits. Staniuta’s children are idealized and fabulous. They are depicted with tenderness. Mikhail Staniuta could be a nice children’s illustrator of magazines and books, but this was unclaimed.

These drawings depict not only the atmosphere of postwar Minsk in the 1950s and 1960s, but also the graphic realism of the Moscow Graphic School (VKHUTEMAS) of the 1920s. His style of painting was getting more and more relaxed from day to day.

Staniuta made no attempt either to exhibit his new and surviving prewar works, or to offer them to museums for purchase. Mikhail Piatrovich simply stored them in his apartment. He did nothing to be famous, but fate decreed otherwise.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН