Міхась Станюта

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 98с.

Мінск 2022

It was decided to open an art studio where lessons in painting, drawing, perspective and art history would be taught under the Department of Fine Arts of the People’s Commissariat for Education in April 1921. The studio teachers were Konstantin Yeliseev, Dmitry Polozov and Konstantin Tikhonov. However, they left Minsk soon. Staniuta made an effort to open art studios ‘Fine Arts’ in Minsk in 1925. They took orders for the making of all kinds of art work, even toys and weaving.

Mikhas Staniuta headed the art studio. There were a few studios in Minsk that time. So, he worked in the studio of the Main Political Directorate, com

5 Leaving Minsk, artist Yeliseev handed over responsibilities to me, saying: ‘You have all the opportunities to work successfully. Set up an exhibition...’ — he recalled.

6 Каталог 1й художественной выставкн подотдела 1430 художественного отдела Главполнтпросвета С.С.Р.Б. Сентябрь 1921 года. Мннск, 1921.

’Arnold Bocklin (1827—1901) is a Swiss painter, graphic artist and sculptor; one of the outstanding representatives of European Symbolism of the 19th century. He is the author of gloomy and anxious paintings depicting the romantic mood of that time.

39

missioned by which he painted the portrait of Karl Marx. He organized two exhibitions of studio members. He taught at the First NineYear Belarusian School named after A. Chervyakov in the 1920s and early 1930s. Children of the working classes and intellectuals studied there. Fiodar Fiodarau, the son of writer Janka Maur, a future theoretical physicist and an academician, also studied at the school. Staniutas student was also young Vital Tsvirka, whose family moved from the village near BudaKasaliova to Minsk. The artist knew Tsvirka’s father well and, at his request, Staniuta began to give his son private lessons8.

Staniuta was an art official for a short time, probably until 1929, when he, Aleksanteri AholaValo and Uladzimir Kudrevich organized the 4th AllBelarusian Exhibition. Staniuta participated in almost every one of the five AllBelarusian exhibitions. The subject of his paintings was changing with the steady ideologization of art: from vivid stilllifes and exquisite portraits of actors (Stefanija Staniuta, Vasil Rahavienka and Volha Vieras) to custommade portraits of the Soviet time (‘Conscript’, ‘Komsomol Collective Farmer’ and Athlete) and paintings on industrialization ordered by the Belarusian State Museum (‘On the Workshop Construction’, ‘Concrete Workers’ and ‘University Town Construction’) for the Minsk Agricultural Exhibition in 1932. They demanded from the artist an active creative position in depicting a man of labor, glorifying the successes of socialist construction.

A few paintings of the 1920s which survived: ‘Cemetery’, ‘StillLife’, ‘Sketch for the Portrait’, ‘Portrait of Vasil Rahavienka, a Studio Member’ and ‘Portrait of Mikhas Filipovich, an Artist’9. In the portrait of his friend Mikhas Filipovich dressed in a fashionable frogged overcoat with a long scarf, Staniuta no

8Vital Tsvirka (19131993), People’s Artist of the BSSR, always respected his first teacher. The inscriptions on the albums of his works for Mikhas Staniuta say about this fact.

9 It is painted in response to the portrait of Filipovich, which has not survived, but it is known from the description of 1921 by Zmitrok Biadulia: “a living, original and fantastic stylized portrait of Staniuta, made ‘unnatural for the face paints, irregular smeared lines, crumpled strokes, but very similar to the original’.

40

ticed the gentleness of character, sad calmness, trustfulness and modesty. One of the private collections contains a sketch for the painting ‘Concrete Workers’ (1928) that is an expressive composition, built on the contrast of silhouettes and a neutral background with sober colors. Four paintings by Staniuta were bought by the Belarusian State Museum in 1928. He received a prize of 100 rubles for one of them ‘University Town Construction.

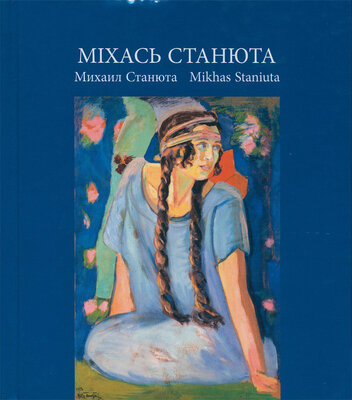

The artist created his masterpiece ‘Sketch for the Portrait’ in 1923. This portrait had different names: ‘Portrait of a Girl’ and ‘Portrait of an Actress’, but never ‘Portrait of the Daughter’ as it is called now. It would be necessary to treat it as a sketch work, but the artist himself later realized that the work was completed. The portrait was displayed at the prestigious exhibition ‘The Art of the Peoples of the USSR’ in Moscow in 1927.

The initiator of this work was Stefanija, an 18yearold studentactress of the Belarusian studio in Moscow. According to her memoirs, ‘...everything turned out quickly and simply, without preparation... I sat on the table, tucking my legs under me, leaning on the table with my hands and looking somewhere to the side, both braids fell to my knees... I remember, as I did the ‘background’, hanging a blue scarf and fixing something like bows of red corrugated paper on it... In one or two sessions, this decorative flat portrait in tempera was ready... I was painted in a conditional manner, theatrical in essence... Shchakatsikhin notes ‘deliberately schematized form’ and ‘bright colors of the background, which make a spectacular spot of color from the sketch’. Together with Uladzimir Kudrevich and Siarhei Kaurousky, Staniuta was referred by him to ‘users of the form of a kind of impressionism’10, arguing that he understood it in his own way and expressed it both in composition and in the application of special techniques.

Stefanija herself directed and ‘staged’ her portrait almost like a miseenscene. The image of a dreamy, a flexible as a reed girl with hopes for happi

“Сучаснае беларускае мастацтва. Праваднік па аддзеле сучаснага беларускага малярства і разьбярства / апрацавалі: М. Шчакаціхін і В. Ластоўскі. Беларускі дзяржаўны музей (БДМ). Менск, 1929. С. 13.

41

ness was perceived as an image of a young Belarus, creative, clean, beautiful, talented, aspiring to the future, with dreams that call ‘to some clear dawns, attract the soul with space’, as Jakub Kolas wrote in the poem ‘Dedication to Stefka Staniuta. The girl did not sit for a long time, rushed away on business, and the second or third session did not happen, although her father tried to complete the sketch. It left the impression of play, freshness and youth, dreaminess and girlish grace, a delicate balance of modern decorativism and softness, exquisite smoothness of lines, pastel colors and color contrasts of Cezannes. The sketchiness and muted tenderness of tone are associated with the peculiarities of tempera, in which pigments are mixed by water, not oil. The artist must take into account the change in tone during the rapid drying of paints, which makes the work process faster. The portrait was published in the edition ‘Pravadnik pa adzdziele sucasnaha bielaruskaha malarstva i razbiarstva (‘Guide to the Department of Contemporary Belarusian Painting and Carving’) of the Belarusian State Museum in 1929. The painting was taken out to Germany from the Belarusian Historical Museum in 1941. It was given back to the State Art Gallery in 1948.

Paired with this work is the portrait of studio member Vasil Rahavienka (1924). It was painted from a famous photograph. It is made in a simplified and a lapidary style against the neutral background. Staniuta depicts the charm of a young man in the role of the Knight Bogatyr from the play ‘Tsar Maximilian’ by Aleksey Remizov. It is the graduation performance of the Belarusian Studio in Moscow. His proper appearance provided him with the role of a romantic hero, a defender of goodness and justice. ‘The hair is combed on both sides, the face is so strange, thin...’ Stefanija described the portrait of her husband11. The halflength portrait of a boy in a wide white blouse with a turndown collar is painted in gentle turquoise tones in the tradition of an intimate portrait.

u Станюта A. Стефання. Мннск, 2001. C. 59.

42

Staniuta was a member of the AllBelarusian Society of Bibliophiles from 1927 to 1930. He studied the culture of books and exlibris. He was a secretary of two societies of artists such as the Belarusian Association of Artists (1925—1927) and the AllBelarusian Society of Artists’ (1927—1930) chaired by Aliaksandr Hrube. His intelligence, literacy and experience in office work were in demand. Staniuta painted intimate works the same years, for example, ‘In the Garden (1927), which is a smallsized painting of the Impressionist genre ‘a woman in a blooming garden on a sunny day’, which makes it possible to show glare, reflexes, pasty strokes, the luminosity of color and the joy of life. The Impressionism was understood as a formal search over the last years. It was the future of the development of Belarusian art.

Everything changed in 1932. All creative associations were revoked, and formal searches were declared bourgeois trends; the Organizing Committee began to operate to create a single Union of Artists of the BSSR for all. The attitude towards the 50yearold artist and his position in the artistic hierarchy of the capital also changed. Mikalaj Shchakatsikhin did not made mention of the name of Staniuta in magazine art reviews for a long time. Aron Kastalianski, a critic and a chronicler of the first years of the Soviet time in the BSSR, considered the artist’s works to be pettybourgeois amateurishness, ‘decadence’, aestheticism, and not worthy of attention. In his book ‘Fine Arts of the BSSR’ (1932), Aron Kastalianski published the artist’s only painting on the labour theme ‘On Construction Site. Concrete Workers’. The artist’s name was in a distorted form ‘Staniura in it.

All this bruised the artist. He stopped exhibiting since 1935. Staniuta became a teacher of drawing in two Minsk schools (No. 4 and No. 9) from the mid1930s. The last exhibition in which the master took part in Minsk was ‘Masters of Belarus during 15 Years’ (1934), ‘Exhibition of Works by Artists of Belarus’ (1935, Moscow) in the premises of the ‘AllRussian Artist’ (AllRussian Cooperative Association Artist’. — N. U.). He felt the inconsistency of his chamber gift with the new, increasingly stringent requirements that were

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН