Аўтаматычна згенераваная тэкставая версія, можа быць з памылкамі і не поўная.

In the 1920s, masters of national culture discovered Belarus anew for themselves and for the world. And Filipovich did it in his individual way which

2 VKHUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios) — the educational establishment in Moscow founded in 1920 by a merger of the First and Second State Free Art Studios, which earlier had been the Stroganov School of Applied Artsthe and Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture.

29

had formed from a range of components. Evidently, the first component was Belarusian culture itself and especially folklore. As early as 1910 he started a sketch album called Belarusian Weaving Patterns and continued to create similar albums in the 1920s {Traditional Wood Carving, Traditional Sashes, Vitebsk Printed Cloth, Belarusian Traditional Costume, etc.), all of them are of great historical value. Impressions of architecture and way of life of Belarusian cities and villages and possibly of artistic exhibitions, which were not so rare in Minsk, were complemented with things he saw and felt in Russian cities — in ancient Moscow with its Tretiakov Gallery, provincial Gzhatsk and colourful Yaroslavl.

In 1922, there was held the first personal exhibition of M. Filipovich in Minsk. Thanks to a fairly detailed article of Zmitrok Byadulya3, we have an idea about the composition and character of that exposition. Three paintings of those mentioned by him are in the collection of the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus now, and they are regarded as selected works of the artist.

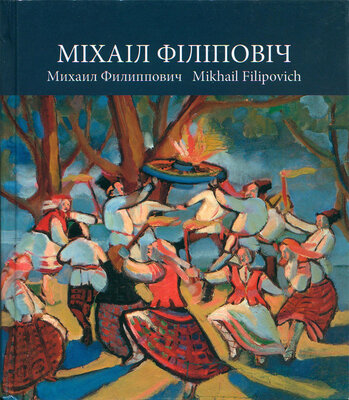

At Kupalle (between 1921—1922) strikes with unbelievable strength, freshness, keenness of world-view and expression characteristic to the artist himself and to the pathos of the time. The painting depicts an unrestrained, almost ecstatic dance of the pagan celebration of the solstice and fertility. The dance as if balances at the edge of chaos. Figures rush about as flames, as fire on a wheel and torches. Colours of clothes glow. First of all, patches of colour are seen, details are barely recognized, “blurred” by swiftness of movement. As in reality, the eye has no time to catch particulars. At the same time the artist showed in detail the character of movement of every figure and individuality of seemingly hardly marked faces and bodies. But the element of warm colours is surrounded and pierced by the element of cold colours — river (legends say that at the Kupalle night waters shine with special ghostly light),

3 Бядуля 3. Выстаўка карцін маляра М. Філіповіча (Памяшканьне Інстытуту Бел. Пэдаг. Тэхнікуму) // Савецкая Беларусь. — 1922. — № 187.

30

blue shadows on white cloths, whirl of ultramarine shading stripes on yellow ground. It is both a real light of the Kupalle night and a symbol of dark forces which awake at the time as legends say, and visualization of comparison of a warm human microcosm and the infinite universe. The painting is interpreted as a symbol of the national element agitated by the revolution and incarnation of the search for happiness, “the flower of fern”. Looking at the Kupalle dance depicted by Filipovich it is hard not to remember the famous fauvist The Dance by Henri Matisse. There is also felt a bit of expressionism, perhaps caused by a high expression of the scene itself.

Round Dance (Lyalnik) (between 1921 —1922) is another unique painting of the decade. Lyalnik is a holiday in honour of Lyalya, the goddess of the Belarusian pantheon, who embodies spring, love, beauty and tenderness. Usually on April 22, the young of a village sang and danced in a ring around the most beautiful girl dressed up and sitting on a high place. The artist painted the atmosphere of a fresh and fragrant spring evening in various but mostly cold colours (with inclusion of red, yellow and brown). Horizontal strokes highlight slow movement and melodic pattern of leisured songs. Depicted idyll with its evening flavour and slightly languishing mood reminds of the poetic style of art nouveau. At the same time, colours are bright and rich enough to associate with traditional art, with a decorated postsilka (carpet).

Fairy-tale Story (between 1921 —1922) — one more painting of the renowned “triad” of the 1920s — is seen as a symbol of eternal struggle between Good and Evil. Z. Byadulya in his article about the exhibition described the painting, apparently quoting the author, as a fight of Kashchei the Deathless and Bogatyr (hero), who symbolized Belarusian Renaissance. The battle of Good and Evil represented not just descriptively but also with violent color-istic “conflicts” of discordant colours. Filipovich acts as an eyewitness of the scene: at the foreground tree branches create an internal frame of the painting, through which as if from the depth of the forest, the artist sees and paints what is going on, thus making people witnesses and participants.

31

Mikhail Filipovich introduced powerful and dramatic colourfulness to the pale city atmosphere and artistic life. But the artist not only participated in the exhibitions of the 1920s. He took an active part in the cultural life of the young BSSR: in 1922—1923 — an artistic instructor of the painting department of the Main Political and Enlightening Committee in Minsk; in 1923 — an executive manager of the decoration of the Belarusian pavilion at the AllUSSR Agricultural Exhibition in Moscow; in 1923—1925 — a head of the artistic department in the Belarusian State Museum. Thanks to the work in the museum, his private advanced study of national art was combined with official duties and new opportunities, which gave great results. His painting, hundreds of sketches, illustrations, small plastic arts are of unique artistic and historical value. In his autobiography the artist would write that in 1921—1928 he created “up to 150 works in oil and 400 drawings in Indian ink, gouache, watercolours, up to 150 illustrations of Belarusian folk tales”4, illustrations to the poems of Y. Kupala, studies of theatrical scenery for the First Belarusian theatre, etc. Filipovich continued and developed the theme of Belarusian history and culture. His works are concrete in topics and forms, and their content is a spiritual concentrate of phenomena and events.

The Battle of the Nemiga (the beginning of the 1920s) has become the classical painting of Belarusian art. There depicted the fight of the Vseslav the Seers army with the Yaroslavichy on March 3, 1067. It was in the description of that event in The Primary Chronicle that Minsk was mentioned for the first time. Also, The Tale of Igor’s Campaign described the battle in both tragic and metaphorical ways. Creating the painting, Filipovich renounced canons of the academic battle-scene painting. He retold the historic event that had taken place more than 900 years ago as an excited witness making the painting a kind of a report. In that visual “report” the artist showed people deprived of

4 Autobiagrophy П The Belarusian State Museum and Archive of Literature and Art. — F. 82. — Inv. 1. — F. 1. — P. 65—66.

32

individuality and possessed by the heat of the battle and the want of victory. The event takes place against the background of eternal and remote beauty of nature, melancholic blue of a forest and tender green of the sky with rounding clouds. Researchers pointed out sketchiness of many-figured works of Filipo-vich, undetailed faces of characters, but all this, as Z. Byadulya5 justly put it, enables viewers to complete the painting.

Besides, the artist created portraits (in particular, of his friend M. Stanyuta and famous Minsk painter P.L. Mrachkouskaya, but, unfortunately, they have not been preserved) and portraits-types, to which may be put The Old Belarusian with a Pipe (the middle of the 1920s). This man’s significance is shown in large and expressive facial features and consistent formal monumentalization of the image. Colouristic power of the image is achieved by the similarity of colours in clothes to natural coloures: a milky-white shirt, bread and earth coloured waisrcoat or kamizelka, a hat or magerka nearly blends with grey clouds. Thus, the character is seemed as a part of nature. A constant interest of the artist, romantic and dreamer, towards painting the sky and clouds should be mentioned. Two of his works at the exhibition of 1921 were named Clouds. The same name bears the sketch of 1942.

Old Shepherd with a Pipe (the first half of the 1920s) is one of folk musicians, whom Filipovich met in his journeys and whom he admired. In this painting the old man sits to the artist against the sun and against the background of the sky, wood and a herd as if he sits to a photographer. Specific harmony is characteristic to the painting, it includes some abruptness and dissonance. Thus, Filipovich showed sounding of folk instruments.

In the 1920s, the artist depicted views of native Minsk in various techniques. Painting architectural monuments, majestic buildings and “common housing estates”, Filipovich combined absolute concreteness and ease of a mo

5 БядуляЗ. Выстаўка карцін маляра М. Філіповіча (Памяшканьне Інстытуту Бел. Пэдаг. Тэхнікуму) И Савецкая Беларусь. — 1922. — № 187.

33

tif with sculptural expressiveness of objects. In buildings’ images as well as in people’s images, the artist was able to show their history and destiny.

Early illustrations to the Belarusian folk tales in watercolours (Blacksmith the Hero, The Blacksmith and One-eyed Sorrow, etc.)6 were made in the art nouveau style: elaborated rhythm of lines, languid tone of subdued coloures, mystical mood. Complicated pattern of rainbow lines make these works resemble carpets. As usual, the artist showed a plot, characters and setting with no particulars, but very accurately and convincingly. All the same, watercolours and graphic drawings are not equal to Filipovich’s oil paintings, though they are interesting and significant, too. Probably, the bigger size base and greater “resistance” of the artistic material were necessary for his creative comfort.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН