Аўтаматычна згенераваная тэкставая версія, можа быць з памылкамі і не поўная.

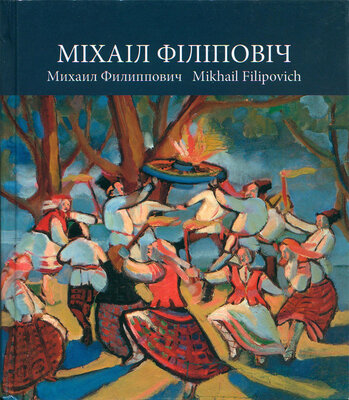

In 1924, the Central Executive Committee of the Union of the Workers in the Arts of Belarus sent Filipovich to Moscow again, to Vkhutemas, as a hope of new Belarusian culture. There, in 1925—1930, his teachers were Robert Falk, the master of intricate colour modeling of form, and Alexander Drevin, who worked pastosely then putting thick layers of paint. Both were great and searching painters connected at the time by the artistic association The Knave of Diamonds7. In the second half of the 1920s, Filipovich followed them in his peculiar style. It is seen in the portrait of G.Y. Grigonis (1927), his neighbour at Markovsky Lane, and The Woman in Namitka (1927), possibly Ksenia Ve-syalouskaya, the artist’s wife. Notwithstanding all their artistic and psychological merits, they resemble well-painted academic works (thorough elaboration of landscape and form, colour and light reproduction in the neo-Realism 6 Based on the collection Fairy-tales and Short Stories of the Belarusians-Poleshuks by A.K. Serzhputousky. 7 The Knave of Diamonds (1910—1917) — the artistic association renouncing the traditions of both academicism and realism of the XIX cent. Colour and plastic schemes in the style of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism, and also the return to the methods of the Russian primitivistic style and traditional toy-making were characteristic to the creative work of the members of the association. 34 style) and are far away from the artist’s previous works. But already in 1928, Filipovich created The Portrait of a Girl in National Costume. This painting stylistically represents lessons of his teachers revised in his own style: model’s reserve, tranquility of a pose, fine work is enlivened with flashes of red and of shirt’s white, which contrast with specks of turquoise and blue. The period of the creative rise of the 1920s was finished for Filipovich with the end of the active “belarusization” period (a policy of protection and advancement of the Belarusian language and recruitment and promotion of ethnic Belarusians). Many workers in the arts and scholars were then accused of lack of understanding of the socialist construction importance. The paintings of Filipovich vanished from the museum’s expositions, he was attacked by artistic critics. Having returned to Minsk after the institution graduation in 1930, he soon left for Moscow again. As Filipovich wrote in his autobiography, still in Vkhutemas he had organized the group of painters from Belarus, took part in the organization and was a member of different creative associations in Minsk and Moscow. In 1930, members of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia elected him group leader of painters who participated in the decoration of Moscow’s plants and factories. In the summer of the same year, he signed a contract with the publishing house Izogiz8 and went to Uzbekistan. Some works created during that artistic trip were bought by the Tretyakov Gallery, were printed as postcards and reproductions. Earlier, thus was published the series of 1929 “about the introduction of tractors to collective farms”. In 1931, Filipovich was sent to Baku to paint portraits of foremost people in industry awarded with the Order of Lenin. Portraits of Fatima Mamedova and of electrician Lamper, as well as a number of pictures of Baku oil fields, were again published by Izogiz. The artist’s works were repeatedly reproduced in magazines. 8 Izogiz — the publishing house of the mass communist propaganda by means of art. 35 Since 1932 Filipovich continued to participate in Belarusian exhibitions, but with paintings of the socialist theme. Among such paintings only one work has been preserved: Land Reclamation in Uzbekistan. When Distributing Water, the Rich Won’t Have It. The painting strikes with its colourfullness and expressivity. The influence of Van Gogh is fairly traced in it. Unexpected angles, compositional acuteness and energetic lines are typical of a range of other Filipovich’s works in the beginning of the 1930s that are known to us only in reproductions. This freedom of expression together with some degree of sincerity enabled Filipovich to retain creative individuality, though the artist actively transformed his work to meet the requirements of the Soviet ideology. In 1932, the party issued a decree on the restructuring of literary organizations and establishment of creative unions. In 1934, the style of Socialist Realism was declared. Filipovich did not escape that trend, for, likely, he had never opposed to the system and was “just a painter”. So, his works naturally became internally empty, shallow and official. Tire creative work of Mikhail Filipovich of the second half of the 1930s is presented in the museum collection mostly by watercolour paintings. For instance, The Cossack Woman from the Don of 1936. There is a note on the back of the painting: “From the delegation of the Don Cossacks with Sholokhov”. In this dynamic and spectacular watercolour painting the smartness of co-loures and distinctness of face dominate and overflow the psychological side. At those years Filipovich often painted children, most likely because of the birth of a son. The Portrait of a Boy, Kindergarten (1935) — unpretentious and touching, but not sentimental images are created in these works. The artist transformed from a bright interpreter of the reality to its catcher. His individuality became apparent to some extent in the selection of the material. However, his peculiar perception of the world and the sensation of the intense and sometimes dramatic life were retained. The artist’s frame of 36 mind in the middle of the 1930s became evident in some works absolutely uncharacteristic of him: monochromic and grey pictures of Moscow regardless the thing the artist depicted, a radiography plant or park. In the work Stone Bridge (1935) violent river waves, the menacing sky and a fragile city between tumultuous elements create the image of the world that had lost peace and safety. In 1939, Mikhail Filipovich came to Minsk and took part in the creation of the theatrical scenery to the opera Kvetka Shchastsya (The Flower of Happiness) by A.E. Turankou. The opera was staged in 1940 in Moscow during the Ten-Day Festival of Belarusian Arts. It is likely that due to the opera another painting about the Kupalle night appeared. In a sense, it summarized twenty years of the pre-war creative work of the artist — from inspired illustration of drama and joy of being to almost not individual depiction of simple and a bit gaudy theatrical mise-en-scene that looked nearly as a parody. Last years of the artist are not well known. His autobiography says that in 1939—1941 he worked in Minsk, participated in exhibitions, created paintings for the historical museum. It was in Minsk that he learnt about the beginning of the war and left for Moscow at the third day. There he continued to work as a painter, and particularly, helped to publish Partyzanskaya Dubinka (The Partisan Cudgel). In 1942—1944, he served in the army. In August, 1944, he came again to Minsk, worked as a head of the artistic department of a publishing house, painted commissions for the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War. Among the artist’s works of the war years there are amazing and unexpected of Filipovich paintings about war. For instance, Cavalry Attack (1942) is full of baroque dynamic and pathos. The artist used the authority of the historical style to glorify the feat of cavalrymen who fought tanks. A contrast between devoted horsemen and “rectangular” Wehrmacht soldiers and tanks looks like a contrast between organic true life and life mechanically organized and bringing death but all the same not able to win. 37 Another work (Tank Attack, the 1940s) shows the Soviet tank attack — in broad daylight tanks and soldiers rush forward through the trees. The artist must have been a witness to such an unthinkable combination of flourishing joy of being and deathly war, so he showed his impressions in the painting. The Landscape with Storks and the study Sunset were made in a more traditional way. Great cheerfulness and illustration of vital energy were always typical of the works of Filipovich. At his last years he painted nature very often escaping thus depression and hardships of life. His small lyrical and dramatic studies prove that he stayed an enthusiastic and tender romantic till the end of his life. It is known, that his last years Filipovich spent in Moscow and died there in 1947. There are still many uncertain details of his life and creative work. More than 100 works of Filipovich (besides magazine graphics and works retained only in reproductions) have been preserved till our day, and it is very rare for the Belarusian artist of the period. His creative work was appreciated at its true value in the 1920s in the publications of Zmitrok Byadulya9 and Mikalai Shchakatsikhin10; and after many decades of half-acknowledgement, in 1971, there was publish a book of Viktar Shmatau11 about his life and creative work that confirmed a true and specific role of Filipovich in the history of Belarusian art. Impressions of the artist’s work in the last years are shown brightly and emotionally in the memoirs of the Minsk actress Stefania Mikha-launa Stanyuta: “... And I saw him working. Do you remember ... he sat usually with a bent head and kept silent... Cheerless, with a sleepy face. He looked far older than he was. You are never to see him combed ... as if he gave up everything including himself. And suddenly a completely different person in 9 Бядуля 3. Выстаўка карцін маляра М. Філіповіча (Памяшканьне Інстытуту Бел. Пэдаг. Тэхнікуму) И Савецкая Беларусь. — 1922. — № 187. 10 Шчакаціхін М. На шляхох да новага беларускага мастацтва. (Нарыс творчасці Міхася Філіповіча) И Полымя. — 1927. — №2. — С. 163—179. 11 Шматаў В. Міхась Філіповіч. — Мінск, 1971. 38 front of you — he began to work. It impressed me greatly; I didn’t realize such things existed. His eyes were live and young, his look was shrewd and tenacious, and his movements were light and quick — so difficult to recognize! He turned out to be just handsome. If someone asked me how inspiration looked like, I would probably see at once Mikhail Filipovich at work in my memory — yes, him, our Mikhail Matsveevich”12.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН