Гістарычны шлях нацыі і дзяржавы

Радзім Гарэцкі, Міхась Біч, Уладзімір Конан

Выдавец: Беларускі кнігазбор

Памер: 348с.

Мінск 2001

The further cultural development of Belarus is connected with establishement and strengthening of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was the Golden Age of Belarusian culture.

In the XHIth-XIVth centuries the national spoken and written languages were developed. A number of historical chronicles, literary pieces, religious treatises, and translations from foreign languages, dating back to the Middle Ages, prove the high cultural level of our people.

A clear national cultural bias was characteristic for the period of the GDL. The culture developed on the basis of Belarusian being the official language of the state. Another peculiarity was that Belarusian culture constantly enjoyed the positive influence of the European culture. A favourable geographical position in the centre of Europe and democratic government were conductive to the assimilation of all the best of what had been created by European civilization. It was quite important that Orthodoxy and the Roman Catholic religion were co-existing on our lands. Catholicism brought West European culture, and a lot of West European masters were invited to work in the GDL. In addition, the citizens of the GDL could freely move to other West European countries to get educated and master different trades.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania enjoyed the vigorous development of science in the Renaissance as well. This process greatly influenced cultural life. The Belarusian Renaissance is one of the finest chapters in our history.

The development of education, book-printing, architecture, and fine arts put Belarus in a leading position among the Eastern Slavic nations. It placed our country far ahead of Muscovy, where there was no Renaissance at all. No wonder, Maksim Bahdanovich in one of his articles of that time named Muscovy ‘a Slavic out-of-the-way corner’.

A considerable contribution to Renaissance culture was made by our great scholar, translator, writer, artist, humanist, and pioneer of printing Frantsishak Skaryna from Polatsk. 23 books of the Bible were translated into Belarusian and printed in Czech Prague in 1517-1519 by Skaryna. His goal was ‘to worship the Lord and to educate common people’. Skaryna’s printed Bible was the first one among Eastern and Southern Slavs. After that the Bible was printed in Germany by Luther, and only half a century later was the same done in Poland. The Russians got their first printed Bible only 47 years after Skaryna’s Bible.

Returning home, Skaryna founded a printing-house in Vilnya in the year 1520. There he printed his Malaya padarozhnaya knizhka (A Small Travelling Book) and Apostal (Apostle).

Some time later other scholars and printers followed his way: Symon Budny, Vasil Tsiapinski, Staphan Zizany, the brothers Kuzma and Lukash Mamonich, Ivan Fedarovich (Fiodarau), and Piatro Mstsislavets. The first printing-house on Belarusian territory worked in Niasvizh in 1562. There Katekhiziz (Cathecism) and Apraudanie hreshnaha chalavieka pierad Boham {Excuses Of Common People When Facing God) by Symon Budny were printed in Belarusian. But in the XVIth-the first half of the XVIIth centuries there were already printing-houses in Vilnya, Bierastsie, Polatsk, Miensk, Mahiliou, Niasvizh, Losk, Liubcha, Zaslauye, Pinsk, Zabludau, Suprasl, luye, Tsiapin (Orsha), Kutsieina, Ashmiany, Bialynichy, Buinichy, and other settlements. Calculations show that by the end of the XVIth century about 400 different books in more than 300 thousand copies had been printed for Belarusians living both in and outside Belarus. These were also religious books for Orthodox, Rome Catholic, and Protestant Belarusians.

In the XVIth-the beginning of the XVIIth centuries a broad system of school education was growing. Schools were opened at Uniate and Orthodox brotherhoods, Protestant communities; some of them were supervised by the Catholic Orders of Piars, Dominicans, and Bernardines. In addition, a network of Jesuitical schools and collegiums, providing a kind of European education, existed in Belarus. The first institution of higher education — the Vilnya Academy — was opened in 1579, and famous scientists from all over Europe were invited to teach there. The Belarusians at the same time were becoming students of Polish, German, Austrian, Dutch, French, Italian, and English universities.

The spread of education and enlightenment was much encouraged by the Reformation, which arose in Europe in the early XVIth century and then spread throughout the Belarusian territory. Belarusian protestants founded schools and printing-houses and created a rich religious literature. In this connection should be mentioned the name of Prince Mikalai Radzivil Chorny (Mikalai Radzivil the Black), who did a great deal to promote education, science, and literature.

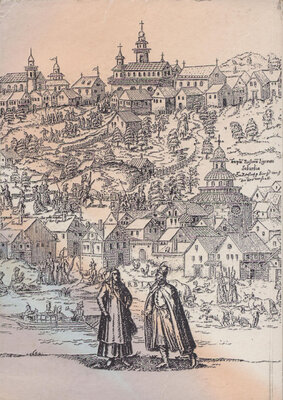

While Belarus was a part of the GDL, every piece of our land became a centre of cultural development. First of all, cultural values were created in big and small settlements numbering over 450 in the middle of the XVIIth century. Cultural centres were also made in the households of Belarusian magnates and noblemen. They considered it an honour to have theatres, picture galleries, libraries, museum collections, printing-houses, art weaving workshops, collections of coins, clothes, arms, and armor at their castles, palaces, or mansions.

Belarusian builders and architects marked their honourable place in history as well. Sophia Cathedral in Polatsk was the first stone temple built on our territory. In the Xllth century there was the Survivor temple (the Survivor-St Euphrasinia Church) in Polatsk, Kalozhskaya Church in Harodnya, Saints Barys and Hlieb Church in Navahradak, Church in Vitsebsk. In the XHIth century the famous Kamianiets tower was erected and is now known as ‘Bielaya Viezha’ (‘the White tower)’. It has become a symbol of Belarus. In the XVIth-XVlIth centuries Suprasl and Synkavichy church-fortresses, a church in the village of Muravanka, and Catholic church in Ishkaldz were erected. These are a few monuments of architecture which have survived until now, but no one knows the actual number of those which have disappeared. Quite a lot of them, like Catholic church in Harodnya, were destroyed in the Soviet period.

Medieval Belarus used to be called a country of castles. Castles were built in Navahradak, Lida, Kreva, Miedniki, Harodnya, Orsha, Heraniony, Miadzel, Zaslauye, Niasvizh, Slutsk, Vitsebsk, Polatsk, Bierastsie, Miensk, Homel, Mstsislaue, Liakhavichy, Hlusk, Liubcha, Stary Bykhau, Karalina, and other settlements. The pearl of Belarusian architecture was erected in the early XVIth century, and even now Mir castle is a real wonder. Such examples of architecture as palaces were introduced in the late XVIth century. The most famous palace ensembles were built in Niasvizh, Halshany, Zaliesie, Ruzhany, Harodnya, Homel, Liubcha, Lahoisk, and other places.

Unfortunately, the major part of our architectural legacy was destroyed in the fires of numerous wars, while the Soviet atheists ruined the rest of the places of worship. A great majority of other cultural heritage, like libraries, picture galleries, collections, archives, was lost. Some of it was moved to Russia, Poland, Lietuva, Sweden, and who knows where else. No one is certain of the location of such treasures as the Cross of St Euphrasinia Polatskaya; the library and museum collections of the Radzivils, Sapiehas, Khraptovichs, Yelskis; the printed works by Frantsysk Skaryna; the Niasvizh collections of the famous Slutsk girdles and cannons; the collections of the Ivan Lutskievich Belarusian museum in Vilnya and the Vilnya museum of antiquities of Yaustakh Tyshkievich; a 40 thousand book library of the Polatsk Academy; and a great many others. The cultural treasures, remaining in Belarus, are one hundredth of those that once existed. At the same time Belarus is one of few countries with no state committee dealing with the returning of the cultural values back home.

In the Middle Ages our country enjoyed the influence both of the Slavic and Latin European cutures. Like a flash in the sky were the literary works in Latin by the poets Mikola Husouski and Yan Vislitski written in the early XVIth century. The first one became famous through his Piesnya pra Zubra {A Song about the Auro ch), the other one through his poem The Prussian War, where a victory at Gruenwald was glorified.

A rich chronical legacy has been left for future Belarusian generations.

Polatsk was the first place in Belarus where chronicles were written. Unfortunately, little is known about the Polatsk chronicle. In the late XHIth-early XVth centuries the Smalensk chronicle appeared. In the XVIth-the beginning of the XVlIth centuries the most famous chronicles were written, such as the Barkulabau chronicle, the Chronicle of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Russia, and Zhamoitsiya, the Chronicle of Bykhaviets, and some others. Matsei Stryikouski and Aliaksandr Hvanini wrote their historical works in the second half of the XVIth century. Memoirs, describing the same historical period, were left by the Belarusian noblemen Fiodar Eulashouski and Yan Tsadrouski.

But further full-blooded cultural development was impossible because of a number of obstacles caused by the political situation in the GDL. The Belarusian people had to go through the policy of strong Polish influence, when being a part of Rzecz Pospolita, and total russification while annexed by the Russian Empire. All the above led to the decline of Belarusian culture to the folklore level.

But despite all difficulties the Belarusian spring has been always sprouting. And it was the first half of the XIX th century, when the earliest signs of Belarusian national-cultural renaissance were seen. In the second half of the XIXth century the process was speeded up to lead to the peak of the Belarusian Renaissance in the beginning of the XXth century. Unfortunately, it was stopped, and this time the Bolsheviks did it. The new Soviet Empire did not provide any of the conditions needed for comprehensive development of the national Belarusian culture. The totalitarian system simply could not afford the free display of national talents.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН