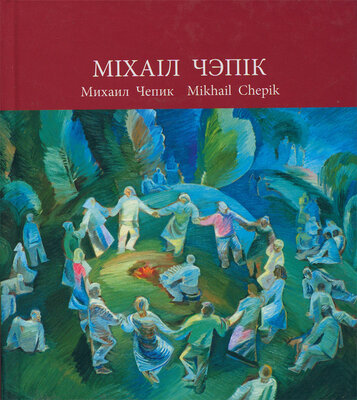

Міхаіл Чэпік

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 98с.

Мінск 2021

О Млхалле Чеплке прл его жлзнл было опубллковано несколько статей в журналах л газетах, лздан едлнственный чернобелый каталог его персональной выставкн12. Современнлкамл он воспрлнлмался как орлглнальный художнлк, но скорее «второго ряда» — без наград л званлй л как бы без особых творческлх достлженлй. Пока нет альбома с пролзведенлямл М. Чеплка, как л его картлн в экспозлцлях музеев, выставкл его пролзведенлй случаются нечасто. Небольшая выставка художнлка прошла в 2008 году13. Но следуюіцлм поколенлям уже лнтересен «феномен Чеплка» — художнлка, который шел протлв потока л сумел в лскусстве создать свой собственный млр: волшебный, ярклй, сказочный, торжественный л определенно белоруссклй, который не перепутаешь нл с чем.

Надежда Усова, йскусствовед

12 Міхаіл Фёдаравіч Чэпік. Выстаўка твораў мастака. Каталог. / уст. тэкст Б. Крэпака.

13 Выставка называлась «Мой Мннск. Пронзведення М. Чепнка, посвяіценные Мннску 1950—1980х годов» н проходнла в галерее Л. ІЦемелева в Мннске.

Vг V/ ikhail Chepik — an artist who approved himself as a theater decorator, whom he was almost all his creative life, as a graphic poster artist, as a production designer, as an authentic easel artist, a master of lyrical landscape and thematic painting, as an innovatormuralist and ambitious experimenter in belarusian soviet painting. He was a versatile artist with strongly pronounced belarusian worldview and an interest in national themes. He painted “On Kupala” (1974), “Bread and Salt” (1980), many landscapes with architectural monuments of Belarus, that became a kind of hymn to the beauty of his Homeland. In each form and genre he was able to preserve diversity and originality. But “his own place” in the history of art in Belarus of the XX century was not still occupied.

Mikhail Chepik did not receive any titles and awards, except for dozens of commendations in the service record and the badge of the Ministry of Culture, the jubilee medal «For Valorous Labor» in honor of the 100th anniversary of V. I. Lenin1. And the artist — a man of exceptional modesty — never had the desire or ambition to occupy any position in the Union of Artists and break through to the top of the artistic hierarchy. But the time distance from the day of his death gives an opportunity to reflect on his art, in which he was able to discover something of his own, distinguishing and personal, which opened the doors of museums for him and made his work a discovery for forethoughtful art collectors.

Mikhail Pilipavich (Michas) Chepik was born on August 3, 1925 in the Zalesye village, Lepel district, Vitebsk region, in a peasant family. A boy from a

1 Mikhail Chepik was proud only of the Order of the Great Patriotic War of the second degree.

30

Belarusian village, the son of an illiterate mother and a despotic father, had the strength and perseverance to make his way to the capital and enter the Moscow Art College named after Kalinin. His fate was to some extent determined by a village teacher who noticed that the boy was carefully drawing pictures from the alphabet book, and bought him paints and pencils in the city. The teacher also advised this specialized college, which trained master carvers for the development of crafts — wood processing and wood painting. He was also the one who convinced Mikhail Chepiks parents to let the 14yearold boy go to Moscow. In 1939, he went to Moscow with a wooden suitcase made of planks and new linen pants. The chairman of the collective farm gave him money for a train ticket. The first time he did not enter — he got lost in the city and was late for the exams. They sent him back and advised to draw more animals from nature, houses — everything that he had seen in the village. He stayed in Moscow, was drawing for a year and was able to enter. He was spending nights in the closet of the college watchwoman who took pity on him, was sleeping on the cot in there and working parttime where possible. He got the nickname “mastak” because that’s what he called himself in Belarusian until he learned how to speak Russian correctly. At the beginning of the war, he left for the Arkhangelsk region in Kotlas to live with his older sister, because Belarus was already under occupation. He worked there as a theater decorator. In 1943, he was drafted into the army, fought as a rifleman on the 3rd Ukrainian Front, liberated Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, fought for Budapest. By the end of the war he was a hospital nurse near Vienna because of his contusion trauma that was a lifetime reminder.

He was mesmerized by the beauty of the snowcapped Alps, the magnificent castles and palaces. When he was commissioned to write slogans for an exhibition of captured weapons, he painted his first postwar landscape on German paper with paints of such a high quality that he never knew can exist2.

2 Завадская PI. Даже сегодня забытые пейзажн Мманла Чепнка выглядят новаторскммм. Полет над городом // Беларусь сегодня. — 2017. — 28 окт. — С. 16.

31

Mikhail Chepik returned to Belarus two years after the end of the war. His mother received death notifications of three of his brothers. The war entered the artist’s work, but it did not become the leading theme unlike the others. Chepik wrote only several works on the war theme, consciously avoiding battle scenes. A former war veteran and paramedic, he knew the real horrors and pain of war and pushed them out of his mind, embodying the war mainly in portraits of veterans, images of military monuments and destroyed cities: “Portrait of the former Red Army soldier I. P. Baltukova” and “1941” (1967), “The Mound of Glory” and triptych “Severe Times” (1969), “Near the Victory Monument” (1970), «To partisans» (1974), “Our Homeland is Behind Us” (1975), «For the Motherland» (1985). Only one portrait of the pioneer hero Marat Kazey “Scorched Youth” (1975) depicts a boy at the moment of his heroic act a few minutes before his death, but the image is so creatively different that this symbolic interpretation still looks innovative. But all these hard military trials of his youth did not deprive Mikhail Chepik of kindness, conscience, joy of life and faith in the beautiful.

In 1947, the Minsk Art School opened on the second floor of the Opera House. Mikhail Chepik was accepted to the second year immediately without exams and selflessly studied with the outstanding teachers Lev Leitman and Valentin Volkov (who taught at the Vitebsk Art School before the war), Vital Tsvirka. Chepik particularly noted Leitman — a witty poet who was interested in the innovation of students, who supported their creativity and individuality. Students recalled how he brought wood to warm the workshop in the winter and not to interrupt drawing classes with the nude model. An excellent watercolorist instilled in Chepik the love for classical watercolor painting, organized pleinairs in the beautiful places in the city that were preserved after the war, such as Loshitsa or Sciapianka. Chepik adopted from Leitman the lightness, sunnines and cheerfulness of the Odessa painting school, where Leitman studied before the revolution.

In photographs from the late 1940s, Mikhail Chepik is a thin, curlyhaired young man with a guitar and a cigarette. But he was completely devoid of the

32

bohemian characters that might be intrinsic to a young artist. Despite the fact that he was surrounded by the famous singers, ballerinas and musicians while he worked at the Opera House as a decorator, before he was assigned as a decorator at the Yanka Kupala Theater.

Mikhail Chepik graduated from college in 1951. What a graduation it was, what names it witnessed! His classmates were Mikhail Savitsky, Leanid Schamialiou, Barys Niapomniaschy, Galina Isaevich, Viktar Gramyka, Izrail Basav. Each of them either fought, was in a concentration camp or was a partisan. Such different artists, and Chepik was at their level. Entering the Art School in 1947, he could not have known that it would actually become his second home for another 35 years, that his whole life, and then the life of his family, would revolve around this theater building by the architect Iosif Langbard. The year after graduation he was admitted to the Opera House as a decorator. He was immediately assigned to decorate “The Sleeping Beauty” by Pyotr Tchaikovsky. The theater was his own world that gave a lot of impressions and brought joy to the life music, friendship, creativity. Mikhail Chepik was able to recognize any opera by three bars and knew all the arias by heart.

Starting from 1953 he began to participate in exhibitions, took part in the Decade of Belarusian Art in Moscow in March 1955 (designed the play “A Girl from Polesie”) and received a Certificate of Honor from the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR. He designed a couple of plays — “Werther” by J. Massenet at the Opera House in 1959, “Little Red Riding Hood” at the Young Spectators’ Theatre. There are preserved sketches for the scenery of the operas “The Decembrists” and “Eugene Onegin” that he exhibited at the AllUnion Exhibition in 1959. Chepik became closely attached to the Opera House during three years of his work there. He didn’t look for a better life (after graduating from the Theater and Art Institute he got a diploma of an easel artist) and a better job. What is more, he couldn’t afford it as he had to keep his family (he married in 1953, three daughters were born one after the other3). Being a workaholic, he was

3 Mikhail Chepik's daughters Valyantina, Lyudmila and Svyatlana became artists.

33

always looking for an additional income. Chepik liked the collective work in the theater: he was responsible, hardworking, companionable. He participated in friendly dinner parties and sketching trips with colleagues Pavel Maslenikav, Ivan Peshkur, National Artist of the BSSR Siarhei Nikalaev, the student of Kanstantin Karovin. The theatrical scenery of the BSSR at that time was dominated by the KarovinGalavin school of painting, which made a great impression on Chepik and gave him additional experience in painting4. Over the years, he painted wonderful portraits of Belarusian performers — the romantic young dancer Mikhail Gryshchanka and National Artist of the BSSR Viktar Charnabajeu, who served in the theater until 2011 and have played more than 100 roles. The portrait of Charnabajeu is carried out by nonstandard, minimalistic, almost posterlike means: a singer in a tuxedo is getting ready to go on stage and play a role: he is deep in himself, sits with his head bowed, powerful hands come to the forefront. The whole figure of the artist is like a clot of creative energy and strength, a spring that will open up in full force on the stage. There are photographs of Charnabajeu in the image of Mephistopheles, Ivan Susanin and others in the background of the work.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН