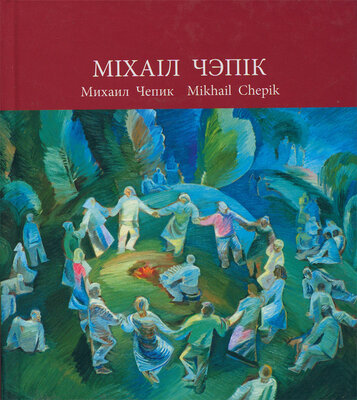

Міхаіл Чэпік

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 98с.

Мінск 2021

Chepik was engaged in selfeducation throughout the whole life: for all money available he bought albums of contemporary artists and subscribed art magazines, took part in all kind of exhibitions held in Minsk (autumn, watercolor, theater decorations, poster art). In 1961, he became a member of the Union of Artists of the BSSR.

Mikhail Chepik was immediately distinguished by a personal perception of the world, a special setting of the eye for color, a recognizable individuality. He has almost no paintings in the spirit of illustrative socialist realism, to which all his classmates paid tribute in the early 1950s. Early master’s works were created during the Thaw, when formal experiments were allowed. The most creative pe

4 Then, in the 80s, when the scenic backstage scenery was replaced by the laconic design of the installation, Chepik lost interest in this work, began to feel weary about it, dreaming of freedom and leisure. He retired in 1985.

34

riod of his work was in the 1960—1980s, when hundreds of works were created, although he had the opportunity to work only in the evenings, on weekends and summer vacation months.

The majority of master’s works were created in the summertime. He refused to participate in all tours in the theater and literally lived in nature, traveling around Belarus, as evidenced by the titles of his works: «Pryluki» (1960), “Lahojsk” (1962), “Liepiel Regional Power Station” and «Astrashytsky Hills» (1966), «Biahoml Woods” (1973), “Spring in Polatsk” (1992), etc.

“Nature was his home. He was not acquainted with material benefits and goods. He directed all his efforts in one direction, all the currents of his nature radiated into his creative work”5, — wrote his friend, neighbor and critic Barys Krepak in the preface to the only catalog of the artists exhibition.

Mikhail Chepik is primarily a landscape painter. He rarely turned to the portrait, there are only about ten of them including the family ones. The portraits of the poets Rygor Baradulin and Maxim Bahdanovich, art critic Viktar Shmatav are distinguished by a special unusual style. Chepik avoids detailing the appearance, creating a certain generalized image of a person, while managing to maintain an elusive resemblance and accurately capture the personality type. According to Chepik, poets, people of culture and creative people in general are celestial, literally soaring in the clouds as if they are out of this world. Sometimes they seem as fabulous ghosts and “people of the ether” to him. This is emphasized by their incorporiety and nonattachment to the earth and visual dissolution of figures in the sky and landscape.

Chepik created portraits of his daughters otherwise. He painted several intimate lyrical portraits of children, imbued with paternal tenderness. He loved to tinker with them, travel together and live in tent. He took them on boat trips, often went out into nature with them. There he tirelessly wrote his improvisations — watercolors that were quick, instant and taken by tone unmistakably. During the day he could paint three large watercolors or gouaches. His scapes are

5 Міхаіл Фёдаравіч Чэпік. Выстаўка твораў мастака. Каталог. / уст. тэкст Б. Крэпака. — Мінск: Беларусь, 1975.

35

often deserted, sometimes with inserted female figures. Chepik’s works quickly became recognizable for their brightness and decorativeness, a special stroke of the brush, color balance and peculiar intonation. His unexpected structure of paintings surprised even his fellow painters with courage, even with them seen enough of all kinds of experiments abroad. They explained his color intensity by the fact that he was a theater artist who was accustomed to “waving a brush” over large surfaces.

Mikhail Chepik’s legacy consists of dozens of paintings, hundreds of watercolors with singing musical rhythms, painted “wet” in a few minutes. No less emotional and artistic are his drawings in pencil or ink. He was working constantly and not just in his studio on Pershamayskaya (and then on Tankavaya), but even at home in front of the TV or in the kitchen waiting for tea, achieving automatism and ease of depicturing nature. His paintings are varied in technique: dynamic, grotesque, or lyrical piece can reach avantgarde minimalism and clarity. It is no coincidence that his drawings and watercolors were chosen for the exhibition of graphics and glass by Belarusian artists in Paris in 1967.

Chepik’s social and political posters are quite different (he worked for several years in “Agitplakat”). They are minimalistic in color, focused on a clear silhouette and font.

As an artist of his time, Chepik looked seamless in the “harsh style” of the 1960s, accepted a kind of “Soviet reform” of the art of socialist realism with his devotion to monumentality and generalization, but avoided its inherent monochrome restraint and excessive heroization of everyday life successfully. He especially liked the works of the new generation artist Viktar Papkov, written as if from the first person and confessionally. Chepik defined his intonation in a lyrical landscape, but also took on multifigure thematic compositions on the “theme of labor” that were obligatory in those years. He performed them easily, without tension, as if “in one breath”, with the scope of Mexican monumentalists about the heroic epic of working people whom he respected. This is tangible in his rural compositions about the work of machine operators that are made in the aesthetics of the 1930s with an unexpectedly bold, almost cinematic per

36

spective and an unexpected angle. Works on the theme of labor — “Harvest Festival” (1972), “Working days” (1973), “Labor Semester” (1975), “Subotnik” (1983) — are peculiar by the dynamics and joy of wellcoordinated teamwork, and “Rye. Young Agronomist” (1978), “Bread and Salt” (1980), on the contrary, by the statics and solemnity, that take us back to the hagiographic stamps in icon painting. His “Working days. The Brigade of Assemblers” is a paraphrase of the picturesque “Builders” (1950) by the French communist artist Fernand Leger, who advised artists “to visit factories and feel the rhythms and plasticity of modernity, to see the worker as the owner of the manufacture Prince Charming”6. Dozens of works were created in the 1960s under the influence of the “austere style” of painting that was interpreted by him in poster style. “Chepik is a writer of common life, but most his works have nothing to do with the shallow storytelling. Chepik perceives the phenomena of life as a real artist, as a poet”7, — as Viktar Shmatav wrote about him. The crowd in his custommade thematic paintings is a contrast to the “uninhabited” deserted landscape with an endless horizon stretching into the distance. In the years of socialist realism and austere painting style, Chepik was an intuitive but convinced formalist: a fauvist and a futurist, a supporter of bright open colors and a planetary vision (although he had never flown). He certainly wouldn’t call himself that. At the beginning of the 1970s, his manner changed to a greater exacerbation, expressiveness. Chepik believed that it was not the plot that was important, but the form of presentation: the dynamics of the texture on the canvas, the rhythm of color, the intensity of the change in its luminosity.

Without leaving Belarus, Chepik suddenly happened to be on a par with the most innovative European trends of the XX century. Unaware of aeropittura (aerial painting) and the late searches and manifesto of the second wave of Italian futurists, his famous contemporaries Dottore and Marinetti, who have private museums, Chepik made practically same discoveries in the outlook on life, col

6 Дубенская Л. A. Рассказывает Надя Леже. M.: Детская лнтература, 1978. — С. 204.

7 Шматаў В. Песня бацькоўскай зямлі // Літаратура і мастацтва. — 1976. — 3 вер. — С. 9.

37

or and composition, but only in the Belarusian rural and urban landscape. He used the same techniques: top view on a parabolic curved earth depicted with bright mixed colors, which gave a feeling of a “foreign spirituality” of the scope, as if it seen from the stratosphere. The same is with rural landscapes, painted as if taken from a soaring hang glider. Of course, these views were not painted from life, but they were very accurate, informative, recognizable, but at the same time, a little alien figurative color fantasies. “Look more up the sky than down at the earth,” as he taught his daughters. Unfortunately, his innovations remained unappreciated by his contemporaries in the Soviet times.

Color was his element, and it is hard to name another artist of more organic color riot mastering and such an incredible courage in the XX century in Belarus. With the color smears of incredible intensity he wrote several works that reflected his childhood memories. The culmination of his color experiments were the works of the early 1980s, such as painting “In the Pasture” (1985). The color literally shimmers and shines on his canvases. Although sometimes it was disturbing for him due to the fact that it was wrong to paint so widely and vividly and it was not what his teachers, realist artists taught him. He was criticized for sketchiness and impulsiveness, “toxic” colors, incompleteness, superficiality, lack of “program” works, lack of depth and philosophy. But deep down, he was aware of his originality, his special gift and his personal worldview. Chepik’s artistry was innate, a modest artist without higher art education was authentic, incredible and European.

He literally lived for art, soared in “elevated dreams”. To his friends, he was a moral authority. Leanid Shchemelev, a brilliant colorist, painted Chepik’s portrait, imbued with respect and admiration for the nobility, spirituality and purity of a friend. Of course, not everyone treated him this way: he did not graduate from the any academy and got no titles. The label of a theater artist associated with the marginality in art, and led to the demeaning attitude from some of the colleagues. In fact, he was not really a theater artist, but more of a decorator, executor of one’s sketches mostly created by certified artists and People’s Artists of the BSSR Sergey Nikalaev, Pavel Maslenikav, National Artist of Ukraine lawhien

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН