Аўтаматычна згенераваная тэкставая версія, можа быць з памылкамі і не поўная.

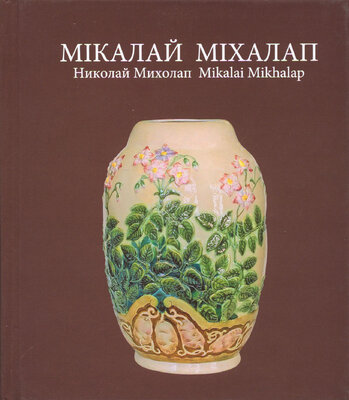

28 equal measure. Such great conditions for work and such experienced teachers were found nowhere else in Russia of that period, so he did not hurry with the graduation from the ceramics faculty and studied there for 6 years. Mikhalap loved to recollect his youth and hard but interesting years in Petersburg with French lessons given by a daughter of the owners of the flat where he slept in a hall on a huge trunk and with visits to the student Belarusian club together with Yanka Kupala who then was a student of general education courses1. It might have been in the club that he became interested in folk art: started to learn about ornaments on tiles and Slutsk sashes for which he searched in old publications of the Imperial Public Library archives, designed theatrical scenery for Belarusian plays, and earned extra money by selling his student works in the school shop. Knowing these circumstances, it is even possible to suggest that an ornamental motif- vytsinanka on the cover of the book of poems Vyanok by Maksim Bagdanovich published in Vilnya in 1913 (it is known that publisher Vatslau Lastouski purchased that drawing on the auction of student works from “an obscure student of von Stieglitz’s School”) could be a work of young Mikhalap. He graduated from the school as art drawing and ceramics artist only in December, 1915, having lived in Petersburg almost 10 years. His graduation project was presented by an earthenware sculpture Bison created under the influence of Impressionist Realism. There has been preserved a small Majolica figurine Bison (1913), which he made back home after long observations of animals in Belavezhskaya Puscha. There M. Mikhalap created a small sculptural sketch from reality according to which a ceramic sculpture was made. Admiring strength and beauty of the animal, he recreated it in movement: as if a bison in a characteristic pose with a low bent head charged on an enemy. The bison image has long been associated with Belarus as its symbol, but few people know that Mikalai Prakopavich was the first Belarusian artist to feel the metaphoricity of that theme and to express it in the decorative sculpture. 1 In 1912, he created Yanka Kupala’s portrait in the etching technique (unfortunately, it disappeared during the war). 29 Years of studying in Petersburg became “the golden” period in the creative life of M. Mikhalap, when he lived in an educated creative environment and could bring his conceptions to realization with enthusiasm. At that time he already showed himself as a real Belarusian author. The artist loved muted colours, preferred complete covering of ceramics with no white background left that made porcelains look heavier and in times they resembled works of such expensive materials as lacquer, nephrite, stone, etc. Some works — Byzantine Vase, the Peacock vase — are made under the influence of the Art-Nouveau style, though Mikhalap never was a bohemian artist: he was not keen on the symbolic theatre or the decadent poetry. Mikalai Prakopavich appreciated the classic style from his youth — decorations on Wedgwood earthenware, Viennese porcelain and Napoleonic “Egyptian service”, which he saw in the museums of Petersburg. The artist’s diploma signed by Princess Obolenskaya, the honorary patron of the school, indicates that he “successfully completed the whole course of this School, took specialized classes on ceramics and etching ... and was awarded title of the artist of applied arts with all rights given to this title and in which he was approved by the Honourable Minister of Trade and Industry”2. After graduation the artist was called up for military service and returned to his native Minsk. He immediately took part in the work of the Committee on Settlement of Refugees from the Western Front. At the 1915 Minsk exhibition “Artists to Warriors” he showed his works for the first time — 8 ceramic pieces: the decorative sculpture Bison Calf, vases Peacock, Little Fish, Bee with Clover, etc. “Majolica works of artist Mikhalap are definitely higher than the school (von Stieglitz’s School in Petrograd. — Author’s note) he finished and outgrew. He is a thoughtful artist, who seriously refines himself”, — wrote critics about the artist’s Minsk debut3. During the first year of the Civil War Mikhalap worked at the construction of military bridges under the Northern Front Roadwork Authority. Later he 2 NAM RB archives. 3Б-н. О выставке «Художники — товарищам воинам» II Минский голос. — 1915. — 13 апр. 30 worked as a teacher in Vitsebsk area, Dvinsk, Beshankovichy, Smolensk area, Novgorod-Seversk near Chernigov. There, in the village of Dekhtyarevka, in May, 1918, he married 25-year-old noblewoman Nadzeya Ivanauna Razumeen-ka, a teacher of the common college, with whom he lived half a century in total harmony. Daughter Volga was born in a year, in the future she would become a biologist. From 1919 he worked in the district Council of National Economy in Novgorod-Seversk as a head of the ceramics workshop, he also tried to organize a glass-producing factory and a craft school in the village of Mashevo. Besides, he worked as a teacher: gave modeling classes in kindergartens, worked in an art class at a school. Next five years (1925—1929) were dedicated to Vitsebsk Art College, where Mikhalap was invited by M. Kerzin, the head of the teaching department, whom he had met in Smolensk area. Both artists had common views on the realistic art. Mikalai Prakopavich became the head of the ceramics department, created a workshop, taught the ceramics technology and composition. The focus of the vocational education was on the folk ceramics. Students went to Vitsebsk suburbs and fairs to buy pottery or make sketches of it. They achieved interesting results in studying pottery production technologies and in creative use of folk plant ornaments in the modern conditions. When M. Kerzin left his post of the director, the ceramics department was closed and the artist left Vitsebsk with regret and returned to his native city. No ceramic works of that time have been preserved: only 2 graphic cityscapes of Vitsebsk and one still-life have survived. The works demonstrate tastefully designed “Petersburg” graphic realism, firm style of Mikhalap, especially in the watercolour drawing Vitsebsk. Kryvaya Street — one of the best Vitsebsk cityscapes of the 1920s in the Belarusian Soviet art drawing. In August, 1930, M. Mikhalap became the head of the ceramics laboratory in the Industrial Research Institute in the mineral technology department in Minsk. He headed the research group on refractory and fine ceramics, studied glazing production for facing tiles. Those issues were highly important for the national economy. Strangely enough, but the transfer to technological research- 31 es on the brink of the struggle against national democrats saved Mikhalap as an artist, because many teachers from Vitsebsk College were arrested and repressed in the early 1930s. In 1933, he was elected a delegate for the Soviet-German Conference “with the casting vote right”, in 1937 — already a member of the Industry Institute Scientific Council responsible for the study of porcelain mass from raw material from the BSSR at the Dulevsky plant. The name of Mikhalap was mentioned during the organization of the 1937 Exhibition “Art and Technology in Modern Life” in Paris. He created special artistic ceramic pieces for the exhibition. At all those posts, Mikalai Prakopavich proved himself a good specialist and excellent organizer. It was not a coincidence that in March, 1939, he was appointed director of the Picture Gallery in Minsk by the special order of the BSSR Council of Peoples Commissars despite being non-partisan. On 15 June 1939, Zvyazda (Star) Newspaper reported that a new building had been given to the gallery — a two-storey house of the former Higher Communist Agricultural School at K. Marks Str. (a classical school for girls before the revolution). Already in June Mikhalap compelled a special decree to create a department of applied arts besides departments of painting, art drawing and sculpture. There was organized a department of artistic industry, where it was intended to deliver all ceramic and glass pieces, and works from wood, fabric and furniture from the number of objects not exhibited in other regional museums in Belarus. Mikhalap acted vigorously: in July, 1939, restoration of new premises for exhibits began. In the first half of June, the gallery admitted around 600 paintings, engravings and sculptures, including 50 engravings by Western masters of the 17th — 18th cc. that were given by the Moscow Museum of Fine Arts. In August of the same year, museums of Vitsebsk and Magileu gave two paintings by I. Repin, paintings by the Itinerants V. Yakobi, Ya. Bashilov, K. Lemokh, V. Katarbins-ki, Yu. Klever, N. Pimonenko and A. Arkhipov, and also two landscapes of the Italian school, Murder of St. Stephen by Salvator Rosa, three marble statues, several pastels by A. Orlovski and 9 paintings by Ya. Sukhadolski from the Gomel History Museum. The State Russian Museum of Leningrad presented 85 prints 32 by Russian artists of the 19th — 20th cc. from the doublet fund to the Picture Gallery. Engravings by Girsha Leibovich were printed from original panels in Petersburg. Mikhalap managed to create the Picture Gallery with a rich collection, a library and to invite professional researchers in just eight months. The Gallery was officially opened on 8 November 1939 to coincide with the celebration of 22 years of the October Revolution. The grand opening was filmed for the newsreel. There were order bearing writers Z. Byadylya and M. Lyn’kou, honoured art workers M. Kerzin and A. Grube among visitors. “The Picture Gallery has in its funds more than 1200 paintings, drawings, sculptures and porcelains. More than 400 exhibits are placed in 15 halls of the Picture Gallery. The exhibits reflect the development of pictorial art from the 18th cent, to our days,” wrote Mikhalap in an article of Literature and Art Newspaper4.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН