Аўтаматычна згенераваная тэкставая версія, можа быць з памылкамі і не поўная.

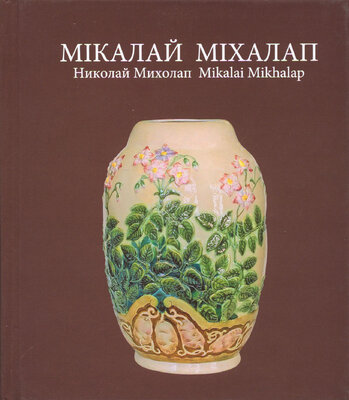

Mikhalap cared about replenishment of the Gallery, especially by works of applied art. A large number of engravings and 51 works of decorative and applied art — the furniture of Alexander II from “the Blue Bedroom” in the Winter Palace — were received from the State Hermitage. The A. S. Pushkin Pictorial Arts Museum in Moscow presented works of European masters from its funds and books on art for the library. After joining regions of Western Belarus and Bialystok to the BSSR the Picture Gallery gained significant artistic objects of value from nationalized property of noble estates and palaces. Works from the Radziwills palace in Nyasvizh were of extrinsic value. From among 264 registered paintings and portraits the committee singled out around 40 family portraits of the 16th — 18th cc., 20 gouaches and drawings of Yu. Falat, 32 Slutsk sashes, furniture, clocks and vases as highly artistic5. About 30 Belarusian icons gathered in expeditions around Minsk, Magileu and Vitsebsk regions were situated in the Gallery. 4 Міхалап M. Карцінная галерэя П ЛіМ. — 1939. — № 39 (453). — С. 4. Высоцкая Н. Нясвіжскія зборы Радзівілаў. Іх фарміраванне, гістарычны лёс, цяпераш-няе месцазнаходжанне і шляхі выкарыстання / Н. Высоцкая, А. Міхальчанка. — Мінск, 2002. — С. 76. 33 First days of the war were the most tragic page of the museum’s history. Minsk bombings started already on July, 24: the city was burning and panic began. It’s known that on June, 23 Mikhalap started to call artists hoping to save treasures with their help but many had been mobilized. Then he went to the Central Committee of the Communist Party but found there only officers hurriedly packing party archives. No orders about the Gallery evacuation were given. Immediately before the beginning of the war the Gallery hosted two exhibitions: “Lenin and Stalin are Organizers of the Belarusian Statehood” (50 sculptures and 221 paintings) and the exhibition of applied art from the Zagorski Museum. The entire main fund was in repositories. It was impossible to evacuate museum collections only by efforts of museum workers: there was no either transport (the only museum lorry had been requisitioned) or work force. Nevetheless, A. Aladava and M. Mikhalap hid about 48 Slutsk sashes, artists took some objects to their own apartments. It was impossible to do more in those circumstances. On June, 26, Mikhalap together with gallery workers and some artists left the city. They managed to board the last train to the rear. On July, 7, he and his family already were in the village of Kryazh near Kuibyshev where he found a post of the drawing and painting teacher at school. Even in such morally hard conditions Mikhalap couldn’t do without creative work. “For the whole time I’ve made 150 sketches of exclusively landscape character, have painted 15 portraits...”, wrote he to Nina Ignatsieva, a gallery worker6. Kryazh winter landscapes of 1942—1943 could be united in a peculiar suite — severe and graphically rough, with the minimal use of colour. It is confronted by a small but warm cycle of watercolour still-lives with vegetables that the artist with his wife grew in their own garden in those hungry years (Onions, Still-Life with Cucumbers, 1943). After the liberation of Minsk, Mikhalap discovered that A. V. Aladava had been appointed the Gallery’s director. “I think, the choice of comrade Aladava is 6 Draft copy of a letter from M. P. Mikhalap to N. Ignatsieva. 8 November 1943. // NAM RB archives. 34 very shrewd. About myself I can tell that I experience a longing for native places and people as never before for all the time that I’ve lived in Kryazh. I feel that I live here only temporally and this feeling binds my hands and feet... And you can’t work as required nowadays. And there is no end to work!”7 On 19 October 1944, Mikhalap returned to Minsk and began to work as an academic secretary in the Architectural Council, and later as a head of the art industry sector of the State Board of Architecture under the BSSR Council of Ministers. He never returned to the Picture Gallery that began to renew after the war. A priceless collection of paintings, furniture and Radziwill sashes had vanished during the years of war. The loss laid heavily in the hearts of former gallery workers, however there was no official charges for everyone remembered too well bitter circumstances of the first days of war. The life in the destroyed city had to be started from the beginning, literally from nothing. He was lucky to get a room in his former house at K. Marks Str. that had survived the war. Mikhalap’s archives from the pre-revolutionary times had been miraculously preserved in the house. When an old man, he brought the archives in an ideal chronological order. In 1945, he was accepted to the BSSR Union of Artists by the recommendation of artist U. Volkau “as the only ceramics artist with professional education”8. He presented 4 watercolours at the landscape exhibition of 1945 and started to work actively as the ceramics artist. In 1946, Mikalai Prakopavich was awarded the medal “For Valorous Labour during the Great Patriotic War”. In 1946, a competition for the best project of light fitting was held in Minsk. Architect U. Karol’, a pupil of Mikhalap, created five variants in co-authorship with his former teacher. Among those five variants there was chosen one with national symbols. An ornament inspired by Slutsk sashes was taken for deco 7 Draft copy of a letter from M. P. Mikhalap to Z. Kanapatskaya from 21.09. 1944.11 NAM RB archives. “ Recommendation for admittance to members of the BSSR Union of Artists. II NAM RB archives. 35 ration. Mikhalap creatively approached its imagery without copying pattern of a specific sash. It seemed as if grief for the lost Slutsk sashes, which they, the museum workers, couldn’t have saved, was printed in the artist’s subconscious and he multiplied their floral ornament at main avenues of Minsk and Gomel. The artist strived to develop national symbols of everyday items while preserving traditional classic forms. In 1948, he created his writing utensils and cutlery (8 and 5 items correspondingly), decorative wall plates, The Partisan Woman panel, flower vases, a reading lamp that became first examples of the artistic ceramics in post-war Belarus. Mikhalap aimed to decorate all everyday items and make them works of applied art. He surely may be called the father of the Belarusian Soviet design. In 1949, on the 30th anniversary of the BSSR, the artist was awarded the order “Badge of Honour” for excellent work and initiative. In 1949, Minsk Porcelain-Faience Factory released its first production. And Mikalai Prakopavich deserved quite a credit for it: he helped to establish technological process and to invite mould makers, model makers and painters. Mikhalap experimented on the use of copper in the faience production and consulted young colleagues. He generously shared the knowledge received in Petersburg in his youth. The factory sorely lacked professional painters to establish the decorative ceramics production and M. Mikhalap visited the restored Higher School of Industrial Art in Leningrad (the former School of Baron von Stieglitz) in the early 1950s to invite professional ceramics artists to Minsk. The first to accept the invitation was N. Klishevich, a graduate of the ceramics faculty, whose task was to decorate residential houses at Peramogi (Victory) Square. Later artist I. Yalatamtsava and furniture designer I. Kharlamau moved to Minsk and stayed there for a lifetime. In the early 1950s, unique anniversary triumphant vases and several vases from the cycle Belarusian Suite (Potato, Flax, Corn, Acorn, Tulip) were produced at Minsk Porcelain-Faience Factory after the sketches of the artist. The earthenware vase Potato (1956) became very famous and was immediately taken to the funds of the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War. Mikhalap chose 36 an oval, potato-like shape and showed all stages of its growth: tubers-fruit at the bottom, leaves and flowers at the top. The vase, though national in spirit, is marked with remarkable Art-Nouveau features traced in flexible lines and pastel colours. Details of the vase were used very tastefully to decorate tiles. The name of Mikhalap is connected with first works of Belarusian art ceramics: after his sketches I. Konyukh and I. Prokharau made vases Anniversary (1953), dedicated to the 20th anniversary of the Polytechnic University, and Soviet Belarus (1953), which was exhibited at the Belarusian Art Decade in Moscow in 1955. An earthenware vase is a distinguishable monument to the Stalinist epoch and to the passionate stylistics of the mid-20th cent, in Belarusian decorative and applied art. It is made in the form of a classic krater. The greater part of its surface is covered with images of sheaves of rye and blooming clover — the artist’s favourite plant. He dedicated a separate work to it (Vase with Clover). Cartouches on both sides of the vase contain a fragment of the congratulations to the Belarusian people on the 70th anniversary of I. V. Stalin, emblems of the automobile plant and the tractor plant (images of a 25-ton automobile and a tractor MTZ-2). Mikhalap had to adapt to the factory raw materials and paint used at that time, that’s why some of his works cannot fully characterize him as the artist. He continued to collaborate with the factory even after his retirement in 1956: he created several small vases of very laconic forms and of grayish-blue and smoky colours. Gradually came the recognition. In 1958, the book Folk and Applied Art in Soviet Belarus with works of M. Mikhalap was published in Minsk, a special attention was paid to the artists creative work in the book of I. Yalatamtsava Art Ceramics of Soviet Belarus9. In 1959, he participated in the All-Union Scientific Conference on Applied Art, his authority helped to establish all-union Decorative and Applied Art of the USSR Journal.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН