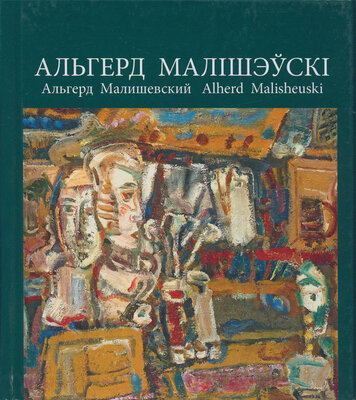

Альгерд Малішэўскі

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 90с.

Мінск 2017

33

The institute had a creative feel, but the difficult post-war time showed anyway. A. Malisheuski told his son that he had been very hungry and had always wanted to eat. Like the others, he drank a lot of water and the body swelled so much that if it was touched, there were left deep marks. To get canvas stretchers, students visited courtyards. They broke the planks out of fences and used them to construct the base for their future training works. Also, A. Ma-lisheuski recalled that formalism had been strictly punished in the institute and Konstantin Korovin had been a forbidden artist. Employees of the related services “surveyed” the creative process. Already during his studies, Alherd Adamavich began to realize that he would have to constantly overcome the tough requirements of socialist realism. Surely, the so-called contractual work and state commissions would appear in his creative biography in the following years. At the same time the artist managed to keep in them a delicate balance between talent and compliance with opportunistic requirements.

In 1952, the first exhibition with the participation of A. Malisheuski took place in Kharkov, where the future maestro presented his work The Group Portrait of KhTZ Stakhanovites. In the same year, he completed his studies successfully creating his graduation painting The First Task, which was exhibited in Kiev in 1953.

In 1953, the artist arrived in Minsk. At the same time, he applied for joining the BSSR Artists’ Union. It should be noted that A. Malisheuski was accepted as a member of this organization only in 1956. Vitaly Kanstantsinavich Tsvirka (then, the BSSR Honoured Art Worker) and Valiantsin Viktaravich Volkau, the BSSR People’s Artist, provided letters of recommendation on the part of artists.

In Minsk, Alherd Adamavich first took a job in the Central Design Workshops of the Belarusian department of the USSR Fund. And soon afterwards he began his legendary teaching at Minsk Art College (now, Minsk State A. Glebau Art College), where he would work until 1981. The famous Belarusian art critic Barys Krepak recalled the following about his like-minded friend: “Malisheuski was an active, communicative and eloquent person, who always dressed like a real dandy, and just like a dandy, he leisurely went to the studio in the morning in an expensive coat and costly glasses. As for his students, he was sometimes caustic, merciless to sloppy work. He used to say: We must shut the door on those with empty souls, whose only purpose is to jump out to the surface.

34

You cannot be calm when dilettantism becomes attached to fashion in order to imitate innovation ...”2. Despite some severity, and sometimes intransigence, students loved their professor. Many of them later became professional artists, whose creative work justly occupied a rightful place in Belarusian contemporary art. There are only some of the names of those who were lucky to learn from A. Malisheuski: Uladzimir Adamchyk (Adam Hlobus), Anatol Baranous-ki, Viachaslau Viarsotski, Uladzimir Zinkevich, Rygor Ivanou, Marya Isaionak, Mikalai Isaionak, Sviatlana Katkova, Uladzimir Kozhukh, Uladzimir Lappo, Zoya Litsvinava, Rygor Loika, Piatro Nazarenka, Rygor Nestserau, Uladzimir Novak, Aliaksandr Pashkevich, Siarhei Rymasheuski, Liudmila Rusava, Siar-hei Salokhin, Rygor Skrypnichenka, Uladzimir Stsepanenka, Rygor Tabolich, Kanstantsin Kharashevich, Henrykh Tsikhanovich, Viktar Shmatau and others. Many of them present an independent art movement; their works are distinguished by the individuality and originality of artistic thinking. This indicates the high degree of professionalism and teaching talent of A. Malisheuski. He instilled in his students a love of painting from nature, which he himself greatly valued and compared with a narrow and consequently right path to the highest truth in creative work. Alherd Adamavich sought to educate the artistic taste of his students on the example of world art works, in particular, on the creative heritage of European modernism and Russian avant-garde, he wanted to take them beyond the understanding of the artist in art that the method of socialist realism dictated. He willingly shared with the youth art albums and professional literature, which was practically nowhere to be found at that time in all of the Soviet Union. He brought good books from abroad. For example, in 1976, he had an occasion to visit Bulgaria for a creative business trip of the USSR Artists’ Union and France thanks to the relatives of his second wife, nee Halina Dzmit-ryeuna Linnikava. According to Siarhei Malisheuski, his father did not take up his brush in Paris, but spent hours in museums in front of the paintings of his favourite artists.

Alherd Adamavich himself saw the origins of his creative search in the European artistic practice of the early twentieth century. He had a close under-

2 Крепак, Б. Цвета Альгерда / Б. Крепак // Культура. — 2014. — № 28(1154). — С. 6.

35

standing of colour in the works of post-impressionists, and he largely learned the philosophical underpinning of painting from Cezanne. These artists were significant to A. Malisheuski, since their work embodied to a greater extent the unity of the world, the integrity of the graphic system — all those categories that the people’s perception possesses — only developed at the professional level and enriched by the intellectual experience of modern man.

The works of A. Malisheuski participated in almost all major republican and all-union exhibitions. Here is what one of the students of Alherd Adamavich, the famous writer and artist Adam Hlobus, writes about it: “An exhibition committee was a council of officials and artists, which decided whether it was possible to show any work at an exhibition or not. The exhibition committee also gave advice on the improvement of works ... Such a long introduction is necessary in order to understand the following words of Alherd: “I have reached such a level that I just bring a canvas to the exhibition committee and leave! And then they call me to tell that they’ve bought the canvas and I go to get my fee”3. And rightly so, today the works of the maestro are in the collections of the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus, the Belarusian State Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War, the National Centre for Contemporary Arts of the Republic of Belarus, the Mahileu Regional P. V. Maslenikau Art Museum, and the Belarusian Union of Artists. However, as an echo of a certain wariness of the authorities towards A. Malisheuski, his dream to teach at the Belarusian Theatre and Art Institute (now, the Belarusian State Academy of Arts) never came true. The older generation of socialist realism painters nicknamed the artist Malbert Madamavich (the nickname is devised from the Belarusian word for an easel and the French ‘madam’ — translators note) for his interest in Western art, and especially in French art, and his creative search, which sometimes balanced on the edge of subject and abstract art.

The creative work of A. Malisheuski is unconventional and not designed for shallow perception. Above all, his works are about the soul searching, the search for colour and form, composition and space. Alherd Adamavich wrote about his

3 Глобус, A. Альгерд. Слова пра мастака і настаўніка майго Альгерда Малішэўскага / А. Глобус // Маладосць. — 2007. — № 4. — С. 113.

36

time and understanding of the artist’s role in art: “The path of our art is thorny, and the garland of a Slavic genius is a crown of thorns. An order issued on behalf of the state led away from art, because art is the perception of material and soul, and not the application of artistic means to the class struggle. It does not contain a mandatory condition to agitate. It does not adorn, does not agitate, does not reflect... Art multiplies human experience, it is a synthetic centre of the past and the future. Those who drew a straight line of art, they were mistaken, because they did not take into account the Personality of the creator and his freedom in choosing a mode of thinking. The Stalinist elite demanded a directed ideology, so a mechanism was established for the transformation of the creative personality into a cog in the machine ... Class dogmatism was higher than universal human values. New canons were formed, as a result of which, the victory was celebrated by convenient slogan platitude and talent and professionalism turned into an outcast”4.

A. Malisheuski was an artist of a wide creative range. He worked in various genres, such as the landscape, still life, portrait and painting. “Alherd was an excellent Belarusian colourist artist, one of the few artists who so ably and artfully mastered paints on canvas believing that it was real pictorial art that first of all should make the audience feel the authors ‘entry’ of the brush into the canvas structure for it to become not just a coloured picture’, but an emotional organism through which the world is perceived as alive, full-blooded and direct”5.

In his best works, A. Malisheuski arranged perspective and space precisely through colour, its saturation and strength. “The maestro strived to make the paint layer to be saturated with light because he related the depth of painting compositions to the assertion of the spiritual space. Light then became the only possibility of its construction in all grounds”6.

4 Малйшевскйй, A. Постепенно ксчезает плесень... C. 31—32.

5 Крепак, Б. Цвета Альгерда. С. 5.

6 Салодкйна, Л. Светлое путешествне в пространство / Л. Солодкнна Н Мастацтва. — 1993, —№6, —С. 32.

37

A. Malisheuski, with the virtuosity intrinsic to him, achieved in his works a true harmony combining the contrasts of cold and warm tones, heaven and earth, spirit and matter. And painting acquired the meaning of content instead of the means in an amazing way. Colour combinations were perceived as the development of the internal state.

An original architectonics to compositions was given through the character of brush strokes, their rhythm, ‘fusion’ of one colour into another. Like a skillful architect, the artist created his ‘image of the world’, the most expressive in landscapes. They are characterized by a high horizon, which allows the land to occupy the main place in a composition. A. Malisheuski sought to identify the colour and structural variability of the state and at the same time preserve the eternal integrity of the land. The colour scheme in his numerous works is often very intense: yellow turns orange, red and crimson tones are laid close to it and blue, almost violet paints are in tense contrast (Gurzuf, 1959; A Day in March, 1962).

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН