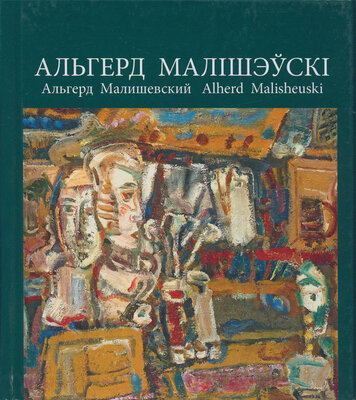

Альгерд Малішэўскі

Выдавец: Беларусь

Памер: 90с.

Мінск 2017

The use of motifs of the road, courtyards and river banks is characteristic of the artist’s landscapes. Everything in them is permeated with silence and consent in nature (The Biarezina, 1961; March. The Last Snow, 1961; To Spring, 1962).

One of the important motifs in the landscapes of A. Malisheuski was the image of the field, which he painted almost throughout his creative career. The artist perceived the image of the field as a manifestation of life where a mysterious and majestic process of rebirth through death took place. A. Malisheuski depicted it in different seasons, which gave an opportunity to convey in painting the most subtle state of air, to trace the complexity of interaction between the colours of land and the light of the sky (Spring. Priluki, 1957; Minsk Area, 1959).

For A. Malisheuski, a person in search of the ideals of good, justice and beauty always remained a measure of things and spiritual perfection. He emphasized that “there are no boundaries for the human spirit, dream, love and compassion. Conscience and mercy are the inner temple”7. Therefore, the artist perceived a person as a dynamic model of the world. So, in the 1960s and early 1970s he

7 Малйшевскый, A. Постепенно лсчезает плесень... C. 32.

38

painted The Portrait of the Head of Crop Growers V. Prystupchyk (1960), The Portrait of the Neurosurgeon S. F. Sekach (1962), A Woman from Polatsk (1968), The Portrait of the Artist A. M. Kashkurevich (1968), The Portrait of a Student (1972), A Young Artist (1973), etc. A. Malisheuskis interest for the work of the Italian artist Renato Guttuso is felt in the works mentioned. It was also extremely important for Guttuso to convey the deep sense of inner tension of modern existence. Like the Italian artist, Alherd Adamavich revealed in his portraits a multifaceted, rich in internal contrasts, image of the epoch and a contemporary full of dignity and strength. Spontaneous emotional excitement and dynamics by actions are expressed in the portraits by A. Malisheuski in rapid rhythms, in strong angular lines and strokes, in the brightness of light, in intense condensation of resonant contrasting colour and forms modeled by an energetic manner of painting.

In his later works, the artist tended to preserve the integrity and harmony of a model. A. Malisheuski made images of contemporaries grow up to major philosophical generalizations. He saw in them principal and significant features, absorbed the audience with the intense plasticity of the pictorial language, la-conicism and emotional culmination. Every time revealing new aspects of the human life in each portrait, Alherd Adamavich did not penetrate into the spiritual state of his models as much as showed their relationship with the outside world, defined the social belonging (The Portrait ofMaryna Meliachenka, 1975; The Portrait of Halina Artsimovich, 1977; The Woman from Polatsk. Nina Knysh, 1981; Nurses. Peace. Victory, 1984, etc.).

A. Malisheuski also continued his creative search in figurative paintings. He strove to gain an insight into the essence of events by means of pictorial art. People in his works are ultimately collective images, types of the artist’s contemporaries emanating powerful vital force (Spring, 1962; A Post-War Year, 1965— 1967; Victory (Soldiers are Sons of the Motherland), 1969; The Oath, 1970; Spring in Chyzhouka. Builders, 1977, etc.).

The painting Milkmaids. Noon (1960) is peculiar in clear, almost graphical silhouettes of figurative motifs and some formality of expression characteristic of the official art of that period. Womens images resemble sculptures in their monumentality, and this impression is strengthened due to the perspectives and the bottom-up point of view.

39

The painting We Will Return (1965) was a truly new ‘word’ in Belarusian painting in its time. That said, its plot is extremely simple: a soldier says goodbye to a child and his severely wounded comrade. However, A. Malisheuski turned it into a high drama of wartime through plastic means. First of all, an acute personal feeling is concentrated in the work. We see the confession painting of one artist, and at the same time, the memory of an entire people.

The motif of the painting The Mother of Partisans (1968) is simple. A group of people stands in a row facing the audience, and the chosen point of view combined with a high horizon brought out almost beyond the canvas literally ties them to the ground. As if the artist seeks to visualize the mother-earth metaphor. The image of an elderly woman, whose figure makes the conceptual centre of the composition despite being shifted to the left, concentrates the generalized image of the Mother. The faces are almost not detailed; the artist focused his attention on the hands toil worn over the years of hard work, weather-beaten in the cold winds of war. The figures are lined up, endowed with similar poses and stand frontal, as in the sacrificial expectation. And although the composition reminds of the group portrait, on the whole it leans toward a genre painting. In fact, village houses behind the backs of the characters replace the horizon and are perceived as a symbolic motif in combination with the frontal figures. If, as a rule, bright, straight and level horizons unfold in front of the audience in the paintings of Stalinist socialist realism, the composition of A. Malisheuski presents a line of life instead with the rhythm of lived-in houses. The composition character is somewhat prearranged and artificial; A. Malisheuski does not specify the circumstances of place and time deliberately.

Alherd Adamavich accumulates many tendencies of the 1960s — 1970s and at the same time he stands apart, beyond artistic movements. The idea of pure painting without alloys of any bias and momentary interests prompted the artist to turn to the genre of still life. The creative work of A. Malisheuski existed in the expanded, mainly pictorial, space of culture and perceived the traditions of classical and modern maestros from Veronese, Titian and El Greco to Cezanne, Van Gogh and artists of the “Jack of Diamonds” group. Work from nature was a prerequisite for him. A. Malisheuski noticed the principle of combining the

40

vision of the far and near in the art of Cezanne, who, as a rule, alternated work in the genre of still life (the experience of near ‘analytical’ perception) and landscape (distant synthetic’ perception) (The Still Life with a Coffee Pot, 1964; Lilac Blooms, 1967; A Still Life, 1967; Russian Trays, 1972).

The Still Life with Masks (1989) is a real rave of paints and a hymn to colour. There is no single point perspective in the painting. A. Malisheuski creates space at the expense of a figurative perspective. The artist manages to balance bright spectral colours in the foreground and tonal hues on distant grounds: red becomes purple, light blue turns to deep blue and yellow to ochreish. Object contours are indistinct and A. Malisheuski deliberately allows deformations in order to fit objects into the general structure, to outline spatial connections. This suggests the use of Cubism techniques, when objects were generalized to the state of geometric bodies and their contours were not closed. Therefore, the eye cannot catch on the form and slips into space all the time. However, A. Malisheuski does not fracture or ‘shift’ the forms, unlike the cubists, adhering to the natural organization. The artist combines several points of view, a top view and a bottom view, achieving a wide panoramic coverage, making the space begin to collapse into a single spherical shape, as in Cezannes paintings.

The Still Life with Masks is one of the final chords in the creative biography of the outstanding Belarusian artist. In this work, the inner impulse, unrestrained expression and the author s intense energy could erase the boundaries between writing, drawing and painting, between space and a plane. A shift from objectivity towards non-objectivity takes place in the painting. The figurative space becomes endless. It practically disengages the forms of the world and their constructiveness.

Alherd Adamavich Malisheuski was several decades ahead of his time. He seemed to foresee that a completely new stage of development would begin in Belarusian art very soon. Attending with great caution to all sorts of ‘new’ manifestos in art, nevertheless, he was one of the few artists from the older generation who supported the talented youth. It is enough to recall the banned 1985 exhibition “1+1+1+1+1+1=6” in the Writers’ Centre, in which participated Adam Hlobus, Ihar Kashkurevich, Eduard Kufko, Eugenia Lis, Siarhei Malisheuski and Liudmila Rusava. From the memoirs of A. Hlobus: “We were

41

condemned by everyone except Alherd Malisheuski. He complimented our courage. He, the one who almost never publicly praised anyone, was up and wished us not to betray art”8.

Alherd Malisheuski enthusiastically embraced the emergence of the famous creative association “Niamiha’17” (existed from 1986 to 2006 in Minsk), the formation of the official art system of Belarus in the 1980s — 1990s. Moreover, he became a participant of the exhibition of this association in 1988 in the Palace of Arts (Minsk). Twenty of his works were exhibited then, four of which are now kept in the collections of the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus (The Portrait of the Artist A. M. Kashkurevich, 1968; The Portrait of a Student, 1972; A Young Artist, 1973; The Portrait of Maryna Meliachenka, 1975). Also, among the participants of the famous exhibition of the creative association were Mikalai Bushchyk, Siarhei Kirushchanka, Anatol Kuzniatsou, Aleh Matsievich, Aliaksandr Miatlitski, Tamara Sokalava, Leanid Khobatau and Ales Tsirkunou9. The unifying factor for them was the departure from the principles of socialist realism and the search for a new language of form. They associated creative liberation with the strengthening of the formal and colouristic principle. Many members of “Niamiha’ 17” gravitated toward non-figurativeness.

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН

КНІГІ ОНЛАЙН